Search by topic

- archaeology

- Building of Local Interest

- charity

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- Listed building

- Mapping Relief

- medieval

- oral history

- poverty

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

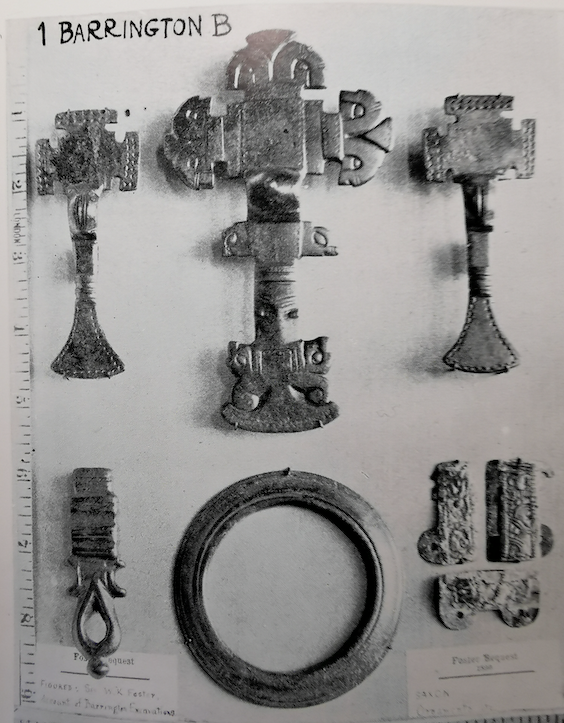

Barrington B Anglo-Saxon cemetery (from Fox 1923)

Barrington B Anglo-Saxon cemetery (from Fox 1923)Cambridgeshire 400 AD to 1066

Overview of Cambridgeshire 400 AD to 1066

This is an edited AI generated summary of the evidence available on Capturing Cambridge for events and developments in Cambridgeshire during the period 400AD to 1066. As such it will be periodically updated and checked as new material is uploaded. Comments are welcome.

Cambridgeshire 400 AD – 1066: A Detailed Historical Study Through Capturing Cambridge

The period between the early fifth century and the Norman Conquest in 1066 represents one of the most complex and formative eras in Cambridgeshire’s history. These centuries — spanning the end of Roman Britain, the Anglo‑Saxon migration, the rise of early English kingdoms, Christianisation, Viking incursions, and the emergence of fortified towns — laid the social, linguistic, religious, and political foundations of the county. Although written sources are scarce, archaeology, landscape patterns, place‑names, and later documentary evidence — much of which is reflected in Capturing Cambridge entries — reveal a rich, evolving regional story.

Cambridgeshire’s strategic geography shaped its development. The River Cam, its tributaries, and the fenland waterways connected settlements across Britain, linking the region to long‑distance trade networks. Meanwhile, higher, drier land along gravel terraces supported farming communities. Through Capturing Cambridge site records, archaeological summaries, and historic building research, we can trace how people lived, worked, worshipped, traded, and defended territory across this 600‑year transition from Roman province to medieval society.

I. Historical Context: Why 400–1066 Matters in Cambridgeshire History

Five interconnected developments defined the era:

1. Withdrawal of Rome and political fragmentation (c. 410)

Roman soldiers left Britain, local elites lost imperial support, and governance shifted to regional warlords and tribal alliances.

2. Anglo‑Saxon migration and cultural transformation (5th–7th centuries)

Newcomers from northern Europe settled, forming villages, introducing Old English language, and gradually reshaping identity.

3. Christianisation (7th–8th centuries)

Monasteries, minsters, parish boundaries, and burial customs spread across the region, altering belief and social organisation.

4. Viking raids and Danelaw rule (9th–10th centuries)

Scandinavian settlement, tribute, military defence, trade, and cultural blending reshaped the eastern counties, including Cambridgeshire.

5. Unification of England and growing state power (10th–11th centuries)

Royal administration, fortified towns (burhs), and legal structures expanded, setting the stage for Norman governance.

Capturing Cambridge entries — particularly those referencing early settlement archaeology — help illuminate these transitions.

II. Case Studies from Capturing Cambridge (Early Medieval Evidence)

A. Roman Legacy and Late Antiquity

1. Roman transport and settlement continuity

While Capturing Cambridge focuses primarily on medieval and later periods, entries for Castle Hill and central Cambridge reference earlier Roman occupation of the site. Archaeological excavations have revealed pottery, building materials, and evidence of Roman infrastructure — suggesting continuity of settlement into the 5th century.

The crossing at what became Magdalene Bridge likely originated as a Roman ford, helping determine later road, market, and property patterns documented today.

2. Roman farms and villas in the surrounding countryside

Although few Capturing Cambridge entries explicitly cover Roman sites, the historical context provided for several villages — including Grantchester — notes Roman-era agricultural activity, indicating a long continuity of rural life beyond the collapse of imperial rule.

B. Anglo‑Saxon Migration, Settlement, and Community Life

3. Early Anglo‑Saxon cemeteries and burials

References within Capturing Cambridge village histories — such as those of Waterbeach and Barrington — note archaeological discoveries of 5th‑ to 7th‑century graves, grave goods, and cremation urns. These finds illustrate cultural transition, shifting belief systems, and the arrival of new communities.

4. Place‑names preserved in Capturing Cambridge entries

Many locations documented in the project have Old English origins — for example:

– Cambridge (Grantebrycge) — “bridge over the River Granta”

– Chesterton — “the farm or estate of Ceaster (a Roman fort)”

– Trumpington — “estate associated with the Trumpa family”

– Grantchester — “Granta‑cæster,” referencing the Roman settlement

Such names reflect settlement continuity and the layering of cultural identity.

5. Village landscapes

Capturing Cambridge entries show that many Cambridgeshire villages — including Histon, Cottenham, and Fulbourn — still follow the street layouts established in the Anglo‑Saxon period. Green‑side settlements, long linear roads, and church‑dominated centres emerged during these centuries.

C. Christianisation and Religious Foundations

6. Parish origins and minster churches

While medieval parish records dominate Capturing Cambridge, many parish boundaries — including those associated with churches in Cambridge such as St Bene’t’s — originated in the 10th and 11th centuries.

St Bene’t’s Church, now documented extensively in Capturing Cambridge, contains Anglo‑Saxon stonework in its tower, representing one of the oldest standing structures in the county and symbolic evidence of early Christianity’s institutional presence.

7. Monastic predecessors

Although the great medieval monastic complexes came later, documentary references linked through Capturing Cambridge suggest earlier religious sites — for example, the pre‑conquest origins of the community later associated with Ely Cathedral.

D. Vikings, Danelaw, and Defence

8. Cambridge under Scandinavian influence

From the late 9th century, Cambridgeshire became part of the Danelaw. Capturing Cambridge entries show that modern street and field patterns may reflect Scandinavian landholding and commercial structures, especially near river crossings.

Archaeology near Castle Hill points to defended settlement activity during this time — perhaps part of the burh system developed under Alfred the Great and Edward the Elder.

9. Trading and river economy

The River Cam served as a commercial artery for both Anglo‑Saxon and Scandinavian traders. Capturing Cambridge’s entries on the city centre and Magdalene Bridge reflect long‑term economic patterns rooted in this period.

E. The Formation of Medieval Cambridge

10. Cambridge as a growing market town

By the 10th and 11th centuries, Cambridge possessed a market, mint, river tolls, and administrative functions. Capturing Cambridge entries emphasize the economic significance of Market Hill, whose location likely dates back to this formative period.

11. Castle Hill and pre‑Conquest governance

Before the Normans built their castle, the hill served as a local power centre. Archaeological discussion referenced in Capturing Cambridge suggests a long history of political use — possibly including moot courts, assemblies, and elite residences.

12. Street plans with early medieval roots

Capturing Cambridge building histories along Bridge Street, Trinity Street, and King’s Parade frequently note that modern property boundaries and street widths may follow earlier Anglo‑Saxon plots.

F. Rural Society, Agriculture, and Landscape Continuity

13. Open‑field farming and shared resources

Many Capturing Cambridge entries trace ridge‑and‑furrow field systems in surrounding villages — a hallmark of late Anglo‑Saxon communal agriculture.

14. Fenland communities

Villages such as Waterbeach and Horningsea reflect early settlement patterns shaped by waterways, fishing, peat cutting, and wetland farming — economic practices still referenced in Capturing Cambridge’s place‑based research.

15. Manor and estate structures

While manorial records are later, Capturing Cambridge references to medieval manor sites suggest earlier elite landholding patterns that emerged before 1066.

III. Themes Emerging from the Period 400–1066

1. Long‑term settlement resilience

Cambridgeshire did not experience full abandonment after Rome — instead, communities adapted, reorganised, and continued agricultural production.

2. Cultural blending and identity formation

Roman, British, Anglo‑Saxon, and Scandinavian influences combined to shape local language, belief, law, and material culture.

3. River‑based connectivity

The Cam and fenland waterways served as economic highways long before modern transport systems, explaining why later Cambridge flourished where it did.

4. Christianisation and social cohesion

Church foundations established patterns of worship, charity, burial, and community that persisted into the medieval and modern periods.

5. Urban beginnings of Cambridge

The roots of the university city lie not in the 13th century but in the market settlement, river crossing, and defensive focus of the 10th–11th centuries.

6. Landscape durability

Fields, roads, parishes, and village footprints remain visible in maps, heritage records, and Capturing Cambridge street histories.

IV. The Role and Limitations of Capturing Cambridge for Early Medieval Study

Capturing Cambridge is particularly valuable for this period because it preserves:

– listed buildings with Anglo‑Saxon architectural elements

– archaeological summaries connected to urban and rural sites

– parish and place‑name histories with pre‑Conquest origins

– environmental and settlement continuity in fenland villages

– public memory of long‑standing landscape features

However, there are limitations:

– fewer primary written records survive before 1066

– many early medieval structures were rebuilt in later centuries

– excavations are selective and often incomplete

– knowledge depends heavily on interpretation of material evidence

Even so, Capturing Cambridge provides a publicly accessible framework for understanding how ancient settlement patterns shape modern life.

V. Conclusion — Early Medieval Foundations of Cambridgeshire

Between 400 AD and 1066, Cambridgeshire transformed from a Roman frontier province into a culturally blended, politically interconnected, economically productive region. It developed the parishes, villages, roads, bridges, and market centres that underlie the county today. Cambridge emerged as a recognisable town — a defended river crossing with merchants, farmers, clergy, and administrators.

Through Capturing Cambridge, we can trace how buildings, streets, landscapes, and place‑names preserve the memory of this era. Though largely invisible beneath later architecture, the early medieval centuries shaped Cambridgeshire’s enduring identity — rural yet connected, scholarly yet commercial, traditional yet adaptive.

Understanding this period allows us to see Cambridgeshire not simply as a product of medieval colleges or Victorian expansion, but as a landscape shaped across millennia — layered with history, community resilience, and continual reinvention.

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0