Search by topic

- archaeology

- architecture

- bricklayer

- Building of Local Interest

- carpenter

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- general labourer

- Great Eastern Railway

- listed building

- medieval

- oral history

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

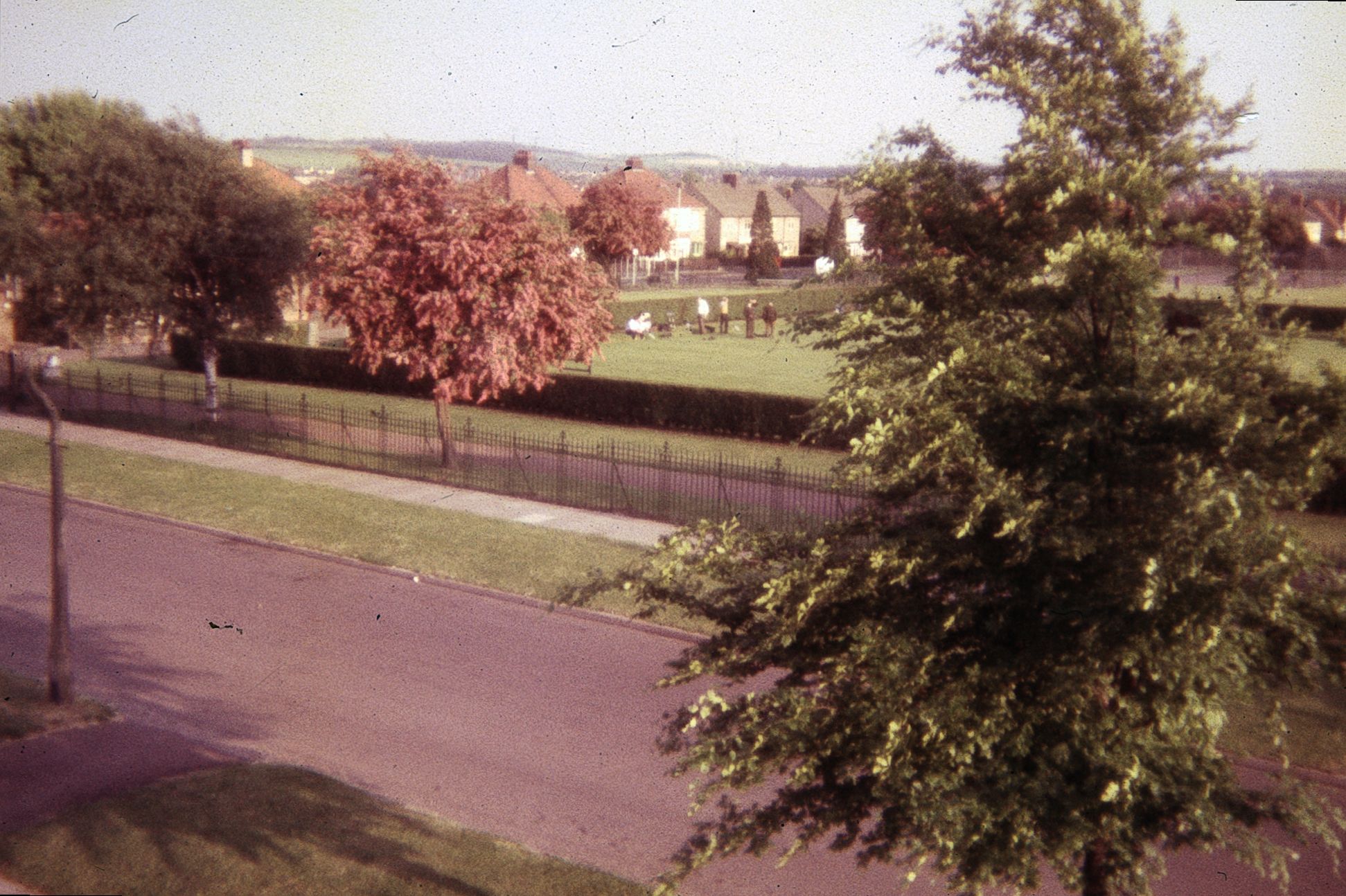

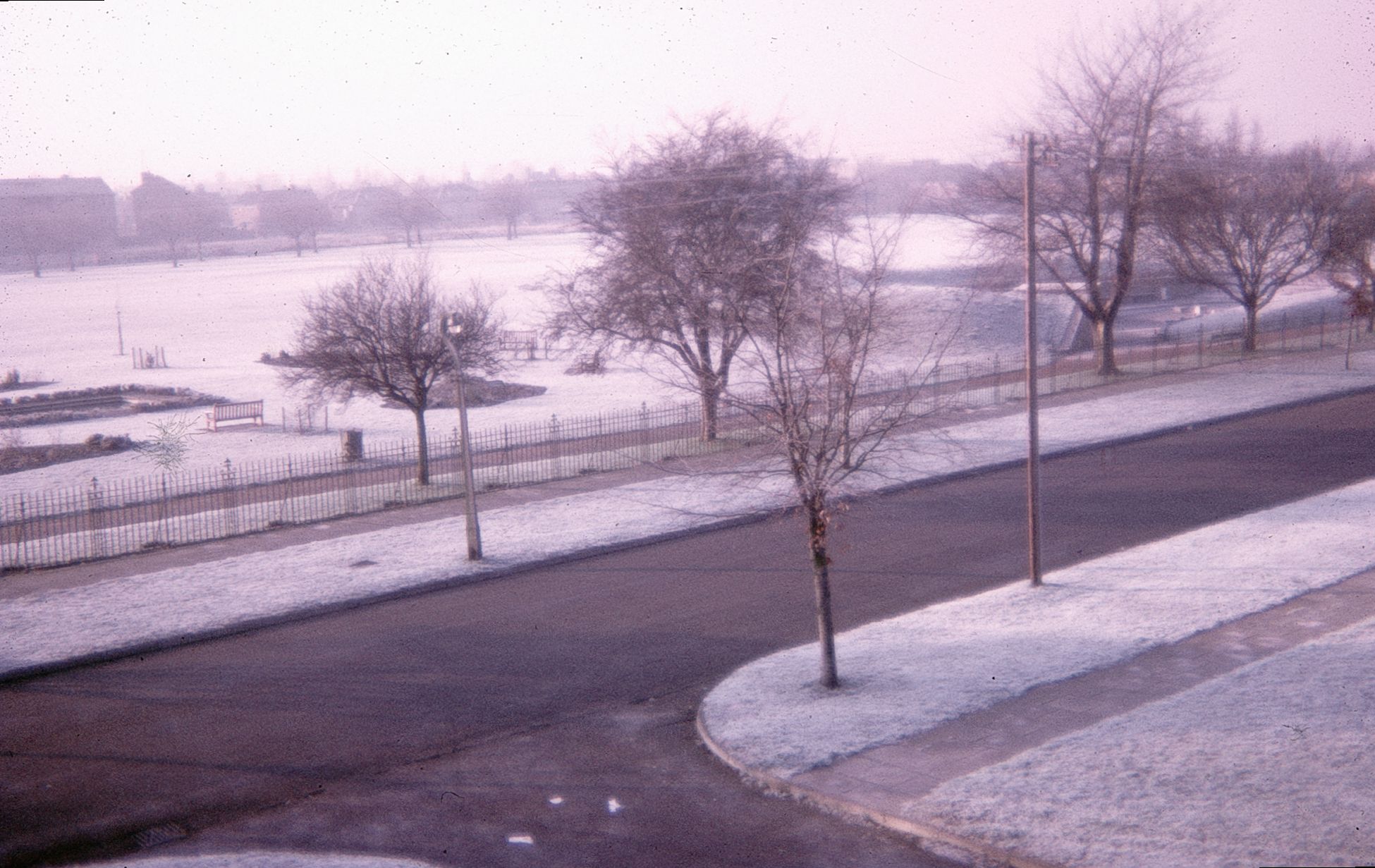

The flats on Davy Road, 1974, courtesy Robert Webb.

The flats on Davy Road, 1974, courtesy Robert Webb.Davy Road in the ’60s and ’70s

Growing up on Davy Road

In 2020 Robert Webb contributed memories of Davy Road in the 1970s where he grew up.

“I grew up in the flats on Davy Road, opposite Coleridge Recreation Ground (‘the Rec’), and lived there until 1979.

My parents moved into their flat in about 1955, when it was new. It was in an end block, on the top floor, with light, airy views over the Rec – which was a selling point I think, although this was a council flat. My parents were among the first occupants in Davy Road. Then in their early thirties, they were an exception to their neighbours though, who were mostly retired.

Kelly’s Directory, 1957 – Davy Road

South side

1 Jeffries, Denis

3 Bruce, Desmond A.

5 Pearson, Levi

North side

2 Bly, P.H.

2a Coleman, Jsph H.

2b Webb, Jn

4 Craft, Edwd A.

4a Faulkner, Mrs

4b Jessop, Jas A.

6 Mallyon Alfd

6a Edwards, Ken

6b Dear, Wm

8 Parker, Stanley

8a Williams, Ronald

8b O’Neill, Harry

Most of the same people were still there twenty years later. Dad and Mr Coleman enjoyed Sunday afternoon chats about their time in the Navy during the war and Mum would stand for hours chatting at the washing lines with neighbours, but otherwise everyone mostly kept themselves to themselves. No one was unfriendly though. From time to time one of the residents would take it upon themselves to wash down the concrete stairs. We even shared a party line with the flat below us when the phone was first installed. This saved walking up to the phone box further along Davy Road (which I think has only in recent years been removed).

The flat came with a modest fitted kitchen, including a pantry, fold-down table and space (just) for a twin-tub washing machine and small fridge. The living room had a fireplace – there was no central heating – and we had an open fire until the mid-sixties, the coal had to be lugged up two flights of stairs from the shed below. Everything was solid and utilitarian and very well designed though, with two built-in cupboards and an airing cupboard. There was also a small balcony which could be used for storage. The floor was tiled with hard, black shiny squares; it wasn’t until the seventies that we had proper wall-to-wall carpets fitted, which was warmer on the feet but not so good for racing Matchbox cars on. The black Bakelite electric wall sockets were too few in number for all the appliances we had by the seventies, especially in my bedroom, when I started buying hi-fi equipment.

There was no double-glazing and window frames were metal and draughty. From my bedroom window you could see the back gardens of the Coleridge Road houses, and in the distance the thin chimney of the cement works, poking up between the roofs like a cigarette. Another window looked out over the Rec and the bowling green, always as flat as a billiard-table and, in the distance, the Gog Magog Hills.

This was a time when many things were still delivered and as a toddler I would stand on a chair at the living room window to watch Rumbelow’s the coalman, the Corona fizzy pop van and the bakery and milk deliveries (it sounds improbable, but in the early 1960s milk floats were still horse-drawn).

The front of the flats looked pretty much as it does today. The central grassy space originally had three broadleaf trees: one of which was struck by lightning in the seventies, losing a branch. The only time I remember this space being used for anything was in 1977 when a small gathering was held for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, attended (and perhaps organised) by a few of the elderly occupants of the flats.

At the rear of the flats were the sheds, each just big enough for a couple of bikes, some garden tools and a bunker for the coal. There was a hard area with washing lines, which I used for ballgames when it wasn’t wash day, and beyond this the gardens. Each flat was allotted a small piece of ground, which Dad and other people used – if they used it at all – to grow things like beans, sprouts and onions. A leftover from the early twentieth century when the whole area was covered in allotments. We also used our patch for firework night: lighting up the cabbages with sparklers and rockets launched from milk bottles.

There were no other families with children living in any of the flats, except for the Pettits, who had a preschool daughter, and the Grants, who also had a daughter a year or two older than me. Both girls were early playmates until they moved elsewhere in the mid-sixties. Once I got to school – first Sedley infants and then Romsey junior – my friends mostly lived in Romsey and the other roads around Coleridge.

Even by 1970 not all the land had been developed – behind our flats, between the single spur of Brackyn Road and the Scout hut at the end of Corrie Road, was a plot of land – ‘The Field’, as we called it – which had never been built on; perfect for us local kids to play on. The Field was finally covered with bricks and mortar in the seventies, but not before we’d made it part of our territory and dug for treasure. We never found more than a few discarded farthings though and, curiously, a hoard of buried seashells.

Otherwise Coleridge Rec was very much our playground: where we would kick footballs, play on the swings and try and climb the trees, and where I took my first steps and learned to ride a bike.

On pocket money day we would cycle round to Greville Stores, on the corner of Greville Road, for flying saucers, sherbet dabs and fruit salads. Or we’d venture over Rustat Road onto the waste ground later occupied by the scientific instruments factory and race along a footpath which ran parallel with the railway just the other side of a high brick wall, down to the cattle market area, which was never locked. There we could sit on parked tractors and explore derelict sheds, under the shadow of Spillers’ crenelated, flour-coloured mill. The railway was actually quite close and on summer nights, with the window open, I would be serenaded by the ghostly creaking and clanging of distant trucks being shunted around the sidings. Getting to the station before the footbridge was built though entailed a long trip round, via Mill Road or Hills Road bridges.

When the Cambridge Folk Festival was on, I would be serenaded by different sounds altogether, the barely-amplified, hazy music wafting over from Cherry Hinton Hall.

Throughout the sixties and seventies, the bank holiday market held on the cattle market ground would attract lots of people and their cars would line Davy Road. It was an unusual sight, as in those days there were few cars parked on the road. The Clifton Road industrial estate was later built on the site.

Improvements were also being made to the Rec. In 1971 the paddling pool was built and this attracted a lot more people, so the park became much busier in the summer.

Davy Road was a great place to grow up, with so many green spaces on the doorstep.

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.