Search by topic

- archaeology

- Building of Local Interest

- charity

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- Listed building

- Mapping Relief

- medieval

- oral history

- poverty

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

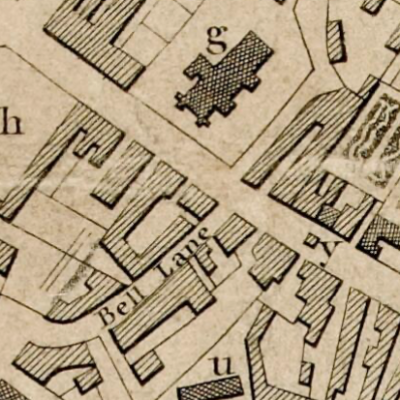

Matcham's Gibbet, Alconbury OS 1887

Matcham's Gibbet, Alconbury OS 1887Matcham’s Gibbet, Alconbury

History of Matcham's Gibbet

Alison Bruce in ‘Cambridgeshire Murders’ gives a detailed account of this murder.

Gervais Matcham was born in 1760 in Yorkshire and ran away from home when he was 12 to become a jockey. He enlisted in the infantry but by 1780 he had deserted and hung around the Huntingdon races. He was forced to reenlist and became a private in the 49th Huntingdonshire Foot Regiment.

In August 1780 he was ordered to be chaperone to the regimental Quartermaster’s son Benjamin Jones, who was the regiment’s 15 year old drummer boy. Benjamin was going to walk about 5 miles to Diddington Hall to collect £7 from Major Reynolds. The money was to buy supplies.

On the way back Matcham slit the throat of Benjamin. He escaped north to York and was press-ganged into the Navy.

Years later Matcham was discharged from the Navy. He was walking across Salisbury plain when he saw visions including one of Benjamin Jones. He confessed at the nearest town and was transported to Huntingdon and convicted.

He was sentenced to be hung at the spot where he had killed his victim and his body, in its red uniform, was left to rot.

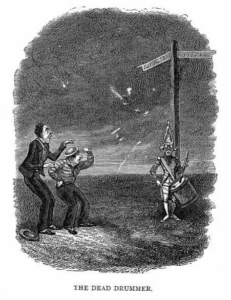

The story was told in a poem, The Dead Drummer: A Legend of Salisbury Plain, and also in the Ingoldsby Legends published between 1840 and 1847.

Oh, Salisbury Plain is bleak and bare,–

At least so I’ve heard many people declare,

For I fairly confess I never was there;–

Not a shrub nor a tree,

Nor a bush can you see:

No hedges, no ditches, no gates, no stiles,

Much less a house, or a cottage for miles;–

— It’s a very sad thing to be caught in the rain

When night’s coming on upon Salisbury Plain.

Now, I’d have you to know

That a great while ago,–

The best part of a century, may be, or so,–

Across this same plain, so dull and so dreary,

A couple of Travellers, way-worn and weary,

Were making their way;

Their profession, you’d say,

At a single glance did not admit of a query;

The pump-handled pig-tail, and whiskers worn then,

With scarce an exception, by sea-faring men,

The jacket,– the loose trousers ‘bows’d up together’–all

Guiltless of braces, as those of Charles Wetherall,–

The pigeon-toed step, and the rollicking motion,

Bespoke them two genuine sons of the Ocean,

And show’d in a moment their real charácters,

(The accent so placed on this word by our Jack Tars).

The one in advance was sturdy and strong,

With arms uncommonly bony and long,

And his Guernsey shirt

Was all pitch and dirt,

Which sailors don’t think inconvenient or wrong.

He was very broad-breasted,

And very deep-chested;

His sinewy frame correspond with the rest did,

Except as to height, for he could not be more

At the most, you would say, than some five feet four.

And, if measured, perhaps had been found a thought lower.

Dame Nature, in fact,– whom some person or other,

— A Poet,– has call’d a ‘capricious step-mother,’–

You saw when beside him,

Had somehow denied him

In longitude what she had granted in latitude.

A trifling defect

You’d the sooner detect

From his having contracted a stoop in his attitude.

Square-built and broad-shoulder’d, good-humour’d and gay,

With his collar and countenance open as day,

The latter –’twas mark’d with small-pox, by the way,–

Had a sort of expression good-will to bespeak;

He’d a smile in his eye, and a quid in his cheek!

And, in short, notwithstanding his failure in height,

He was just such a man as you’d say, at first sight,

You would much rather dine, or shake hands, with than fight!

The other, his friend and companion, was taller,

By five or six inches, at least, than the smaller;–

From his air and his mien

It was plain to be seen,

That he was, or had been,

A something between

The real ‘Jack Tar’ and the ‘Jolly Marine.’

For, though he would give an occasional hitch,

Sailor-like to his ‘slops,’ there was something, the which,

On the whole savour’d more of the pipeclay than pitch.–

Such were now the two men who appear’d on the hill,

Harry Waters the tall one, the short ‘Spanking Bill.’

To be caught in the rain,

I repeat it again,

Is extremely unpleasant on Salisbury Plain;

And when with a good soaking shower there are blended

Blue lightnings and thunder, the matter’s not mended;

Such was the case

In this wild dreary place,

On the day that I’m speaking of now, when the brace

Of trav’llers alluded to quicken’d their pace,

Till a good steady walk became more like a race

To get quit of the tempest which held them in chace.

Louder, and louder

Than mortal gunpowder,

The heav’nly artillery kept crashing and roaring,

The lightning kept flashing, the rain too kept pouring,

While they, helter-skelter,

In vain sought for shelter

From what I have heard term’d, ‘a regular pelter;’

But the deuce of a screen

Could be anywhere seen,

Or an object except that on one of the rises,

An old way-post show’d

Where the Lavington road

Branch’d off to the left from the one to Devizes;

And thither the footsteps of Waters seem’d tending,

Though a doubt might exist of the course he was bending,

To a landsman, at least, who, wherever he goes,

Is content, for the most part to follow his nose;–

While Harry kept ‘backing

And filling’– and ‘tacking,’–

Two nautical terms which, I’ll wager a guinea, are

Meant to imply

What you, Reader, and I

Would call going zig-zag, and not rectilinear.

But here, once for all, let me beg you’ll excuse

All mistakes I may make in the words sailors use —

‘Mongst themselves, on a cruise,

Or ashore with the Jews,

Or in making their court to their Polls and their Sues,

Or addressing those slop-selling females afloat — women

Known in our navy as oddly-named boat-women.

The fact is, I can’t say,I’m versed in the school

So ably conducted by Marryat and Poole;

(See the last-mentioned gentleman’s ‘Admiral’s Daughter’)

The grand vade mecum

For all who to sea come,

And get, the first time in their lives, in blue water;

Of course in the use of sea terms you’ll not wonder

If I now and then should fall into some blunder,

For which Captain Chamier, or Mr. T. P. Cooke

Would call me a ‘Lubber,’ and ‘Son of a Sea-cook.’

To return to our muttons — This mode of progression

At length upon Spanking Bill made some impression,

–‘Hillo, messmate, what cheer?

How queer you do steer!’

Cried Bill, whose short legs kept him still in the rear,

‘Why, what’s in the wind, Bo?– what is it you fear?’

For he saw in a moment that something was frightening

His shipmate much more than the thunder and lightning.

‘Fear?’ stammer’d out Waters, ‘why, HIM!– don’t you see

What faces that Drummer-boy’s making at me?’

— How he dodges me so

Wherever I go?–

What is it he wants with me, Bill,– do you know?’

‘What Drummer-boy, Harry?’ cries Bill in surprise,

(With a brief explanation, that ended in ‘eyes,’)

‘What Drummer-boy, Waters?– the coast is all clear,

We haven’t got never no Drummer-boy here!’

–‘Why, there?– don’t you see

How he’s following me?

Now this way, now that way, and won’t let me be!

Keep him off, Bill — look here —

Don’t let him come near!

Only see how the blood-drops his features besmear!

What, the dead come to life again!– Bless me!– Oh dear!’

Bill remark’d in reply, ‘This is all very queer —

What, a Drummer-boy — bloody, too — eh!– well, I never —

I can’t see no Drummer-boy here whatsumdever!’

‘Not see him!–why there;–look!–he’s close by the post–

Hark!– hark!– how he drums at me now!– he’s a Ghost!’

‘A what?’ returned Bill,– at that moment a flash

More than commonly awful preceded a crash

Like what’s call’d in Kentucky ‘an Almighty Smash.’–

And down Harry Waters went plump on his knees,

While the sound, though prolong’d, died away by degrees:

In its last sinking echoes, however, were some

Which, Bill could not help thinking, resembled a drum!

‘Hollo! Waters!– I says,’

Quoth he in amaze,

‘Why, I never see’d nuffin in all my born days

Half so queer

As this here,

And I’m not very clear

But that one of us two has good reason for fear —

You to jaw about drummers with nobody near us!–

I must say as how that I thinks it’s mysterus.’

‘Oh, mercy!’ roar’d Waters, ‘do keep him off, Bill,

And, Andrew, forgive!– I’ll confess all!– I will!

I’ll make a clean breast,

And as for the rest,

You may do with me just what the lawyers think best

But haunt me not thus!– let these visitings cease,

And your vengeance accomplish’d, Boy, leave me in peace!’

— Harry paused for a moment,– then turning to Bill,

Who stood with his mouth open, steady and still,

Began ‘spinning’ what nauticals term ‘a tough yarn,’

Viz.: his tale of what Bill call’d ‘this precious consarn,’

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

‘It was in such an hour as this,

On such a wild and wintry day,

The forked lightning seem’d to hiss,

As now, athwart our lonely way,

When first these dubious paths I tried —

Yon livid form was by my side!–

‘Not livid then — the ruddy glow

Of life, and youth, and health it bore!

And bloodless was that gory brow,

And cheerful was the smile it wore,

And mildly then those eyes did shine —

— Those eyes which now are blasting mine!

‘They beam’d with confidence and love

Upon my face,– and Andrew Brand

Had sooner fear’d yon frighten’d dove

Than harm from Gervase Matcham’s hand!

— I am no Harry Waters — men

Did call me Gervase Matcham then.

‘And Matcham, though a humble name,

Was stainless as the feathery flake

From Heaven, whose virgin whiteness came

Upon the newly-frozen lake;

Commander, comrade, all began

To laud the Soldier,– like the Man.

‘Nay, muse not, William,– I have said

I was a soldier — staunch and true

As any he above whose head

Old England’s lion banner flew;

And, duty done,– her claim apart,–

‘Twas said I had a kindly heart.

‘And years roll’d on, and with them came

Promotion — Corporal — Sergeant — all

In turn — I kept mine honest fame —

Our Colonel’s self,– whom men did call

The veriest Martinet — ev’n he,

Though cold to most, was kind to me!–

‘One morn — oh! may that morning stand

Accursed in the rolls of fate

Till latest time!– there came command

To carry forth a charge of weight

To a detachment far away,–

— It was their regimental pay!–

‘And who so fit for such a task

As trusty Matcham, true and tried,

Who spurn’d the inebriating flask,

With honour for his constant guide?–

On Matcham fell their choice — and He,–

‘Young Drum,’– should bear him company!

‘And grateful was that sound to hear,

For he was full of life and joy,

The mess-room pet — to each one dear

Was that kind, gay, light-hearted boy.

— The veriest churl in all our band

Had aye a smile for Andrew Brand.–

‘– Nay, glare not as I name thy name!

That threatening hand, that fearful brow

Relax — avert that glance of flame!

Thou see’st I do thy bidding now!

Vex’d Spirit, rest!–’twill soon be o’er,–

Thy blood shall cry to Heav’n no more!

‘Enough — we journey’d on –the walk

Was long,– and dull and dark the day,–

And still young Andrew’s cheerful talk

And merry laugh beguiled the way;

Noon came, a sheltering bank was there,–

We paused our frugal meal to share.

‘Then ’twas, with cautious hand, I sought

To prove my charge secure,– and drew

The packet from my vest, and brought

The glittering mischief forth to view,

And Andrew cried,–No!–’twas not He!–

It was THE TEMPTER spoke to me!

‘But it was Andrew’s laughing voice

That sounded in my tingling ear,

–“Now, Gervase Matcham, at thy choice,”

It seem’d to say, “are gauds and gear.

And all that wealth can buy or bring,

Ease,– wassail,– worship,– every thing!

‘”No tedious drill, no long parade,

No bugle call at early dawn;

For guard-room bench, or barrack bed,

The downy couch, the sheets of lawn;

And I thy Page,– thy steps to tend,

Thy sworn companion,– servant,– friend!”

‘He ceased — that is, I heard no more,

Though other words pass’d idly by,

And Andrew chatter’d as before,

And laugh’d — I mark’d him not — not I.

‘”Tis at thy choice!” that sound alone

Rang in mine ear — voice else was none.

‘I could not eat,– the untasted flask

Mock’d my parch’d lip,– I pass’d it by.

“What ails thee, man?” he seem’d to ask.–

I felt, but could not meet his eye.–

‘”Tis at thy choice!”– it sounded yet–

A sound I never may forget.

–‘”Haste! haste! the day draws on,” I cried,

“And Andrew, thou hast far to go!”–

“Hast far to go!” the Fiend replied

Within me,–’twas not Andrew — no!

‘Twas Andrew’s voice no more –’twas He

Whose then I was, and aye must be!

— On, on we went:– the dreary plain

Was all around us — we were Here!

Then came the storm,– the lightning,– rain,–

No earthly living thing was near,

Save one wild Raven on the wing,

— If that, indeed, were earthly thing!

‘I heard its hoarse and screaming voice

High hovering o’er my frenzied head,

‘”Tis Gervase Matcham, at thy choice!

But he — the Boy!” methought it said.

— Nay, Andrew, check that vengeful frown,–

I loved thee when I struck thee down!

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

”Twas done! the deed that damns me — done

I know not how — I never knew;–

And Here I stood — but not alone,–

The prostrate Boy my madness slew,

Was by my side — limb, feature, name,

‘Twas HE!!– another — yet the same!

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

‘Away! away! in frantic haste

Throughout that live-long night I flew —

Away! away!– across the waste,–

I know not how — I never knew.–

My mind was one wild blank — and I

Had but one thought,– one hope — to fly!

‘And still the lightning plough’d the ground,

The thunder roar’d–and there would come

Amidst its loudest bursts a sound

Familiar once — it was — A DRUM!–

Then came the morn,– and light,– and then

Streets,– houses,– spires,– the hum of men.

‘And Ocean roll’d before me — fain

Would I have whelm’d me in its tide,

At once beneath the billowy main

My shame, my guilt, my crime to hide;

But HE was there!– HE crossed my track,–

I dared not pass — HE waved me back!

‘And then rude hands detain’d me — sure

Justice had grasp’d her victim — no!

Though powerless, hopeless, bound, secure,

A captive thrall, it was not so;

They cry ‘The Frenchman’s on the wave!’

The press was hot — and I a slave.

‘They dragg’d me o’er the vessel’s side;

The world of waters roll’d below;

The gallant ship in all her pride

Of dreadful beauty sought her foe;

— Thou saw’st me; William in the strife —

Alack! I bore a charmed life!

‘In vain the bullets round me fly,

In vain mine eager breast I bare;

Death shuns the wretch who longs to die,

And every sword falls edgeless there!

Still HE is near;– and seems to cry,

“Not here, nor thus, may Matcham die!”–

‘Thou saw’st me on that fearful day,

When, fruitless all attempts to save,

Our pinnace foundering in the bay,

The boat’s-crew met a watery grave,–

All, all — save one — the ravenous sea

That swallow’d all — rejected Me!

‘And now, when fifteen suns have each

Fulfill’d in turn its circling year,

Thrown back again on England’s beach,

Our bark paid off — HE drives me Here!

I could not die in flood or fight–

He drives me HERE!!’–

‘And sarve you right!

What! bilk your Commander!– desart — and then rob!

And go scuttling a poor little Drummer-boy’s nob;

Why, my precious eyes! what a bloodthirsty swab!–

There’s old Davy Jones,

Who cracks sailors’ bones

For his jaw-work, would never, I’m sure, s’elp me Bob,

Have come for to go for to do sich a job!

Hark ye, Waters,– or Matcham,– whichever’s your purser-name,

— T’other, your own, is, I’m sartain, the worser name,–

Twelve years have we lived on like brother and brother!

Now — your course lays one way, and mine lays another!’–

‘No, William, it may not be so;

Blood calls for blood!–’tis Heaven’s decree!

And thou with me this night must go,

And give me to the gallows-tree!

Ha!– see — He smiles — He points the way!

On, William, on!– no more delay!’

Now Bill,– so the story, as told to me, goes,

And who, as his last speech sufficiently shows,

Was a ‘regular trump,’– did not like to ‘turn Nose;’

But then came a thunder-clap louder than any

Of those that preceded, though they were so many:

And hark!–as its rumblings subside in a hum,

What sound mingles too?– By the hokey– A DRUM!!

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I remember I once heard my Grandfather say,

That some sixty years since he was going that way,

When they show’d him the spot

Where the gibbet — was — not —

On which Matcham’s corse had been hung up to rot;

It had fall’n down — but how long before, he’d forgot;

And they told him, I think, at the Bear in Devizes,

The town where the Sessions are held,– or the ‘Sizes,

That Matcham confess’d,

And made a clean breast

To the May’r; but that after he’d had a night’s rest,

And the storm had subsided, he ‘pooh-pooh’d’ his friend,

Swearing all was a lie from beginning to end;

Said ‘he’d only been drunk —

hat his spirits had sunk

At the thunder — the storm put him into a funk,–

That, in fact, he had nothing at all on his conscience,

And found out, in short, he’d been talking great nonsense.’–

But now one Mr. Jones

Comes forth and depones

That fifteen years since, he had heard certain groans

On his way to Stonehenge (to examine the stones

Described in a work of the late Sir John Soane’s,)

That he’d follow’d the moans, And, led by their tones,

Found a Raven a-picking a Drummer-boy’s bones!–

— Then the Colonel wrote word

From the King’s Forty-third,

That the story was certainly true which they’d heard,

For, that one of their drummers, and one Sergeant Matcham,

Had ‘brush’d with the dibs,’ and they never could catch ’em.

So Justice was sure, though a long time she’d lagg’d,

And the Sergeant, in spite of his ‘Gammon,’ got ‘scragg’d;’

And people averr’d

That an ugly black bird,

The Raven, ’twas hinted, of whom we have heard,

Though the story, I own, appears rather absurd,

Was seen (Gervase Matcham not being interr’d),

To roost all that night on the murderer’s gibbet;

An odd thing, if so, and it may be a fib — it,

However’s a thing Nature’s laws don’t prohibit.

— Next morning they add, that ‘black gentleman’ flies out

Having picked Matcham’s nose off, and gobbled his eyes out!

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0