Search by topic

- archaeology

- Building of Local Interest

- charity

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- Listed building

- Mapping Relief

- medieval

- oral history

- poverty

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

Romsey Town, 1966-2006

A Community in Transition

In 2006 Allan Brigham and Colin Wiles wrote a paper for the Chartered Institute of Housing Eastern Branch entitled ‘Bringing it all back home: Changes in Housing and Society 1966-2006’. The following is the introduction to the section on Romsey Town.

’It was said that one could be born and die in Romsey Town and have everything you needed in between without ever leaving Mill Road’ – Wendy Maskell

King’s College Chapel rises cathedral-like over Cambridge, a unique building renowned around the world for its music at Christmas. It is the symbol of the City. Many people believe that the University created Cambridge but the town existed long before the University arrived in 1284. ‘Town’ is older than ‘gown’.

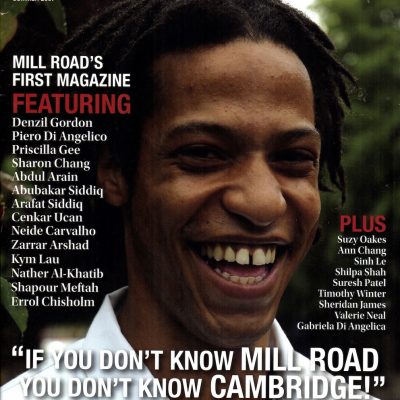

If you walk from the city centre across Parker’s Piece, one of the most magnificent urban spaces in England, you will come to a legendary central lamp upon which is written “Reality Checkpoint”. This is where gown ends and the town begins. Walk to the far corner of the Piece and follow Mill Road with its multi ethnic shops and after a few minutes you will come to a railway bridge. Over the bridge is Romsey Town – a dense community of narrow streets where many front doors open onto the pavement.

Romsey Town had its origins in the Enclosure Acts of the 1800s, which dismantled the open fields that had hemmed in the town for centuries (its first green belt). The small strips of land were re-assembled and many were sold for housing. The railway arrived in the mid nineteenth century and most of the houses were built between 1885 and 1895 with the street pattern following the old field boundaries. It was the era of high Empire, reflected in the names of the public houses – The Jubilee, The Empress – and in street names – Malta, Cyprus, Suez, and Hobart. The parallel rows of streets ended to the north in footpaths that led to the uninhabited Coldhams Lane and the empty Coldhams Common where coprolites were mined.

The railway divided Romsey Town from the city. The area grew as a distinct and self supporting community with its own shops, churches and leisure facilities. This created a sense of cohesion and community. It was a local, not a global world where work and leisure had to be within easy reach, where personal transport was limited to the bicycle, and television was in the distant future.

There were fine gradations within the terraces, and some streets had a better reputation than others. Width mattered – a frontage of 13 ft meant the front door opened into the front room, while 15 ft would give you a hallway and privacy. Most houses had three bedrooms, but in some access to the rear bedroom would be through the middle bedroom. Most toilets were outside, and the bathroom was a tub on the living-room floor once a week. The larger terraces – often home to the local elite, the engine drivers – had bay windows and front gardens. Nearly all had long gardens, not the small yards of central Cambridge.

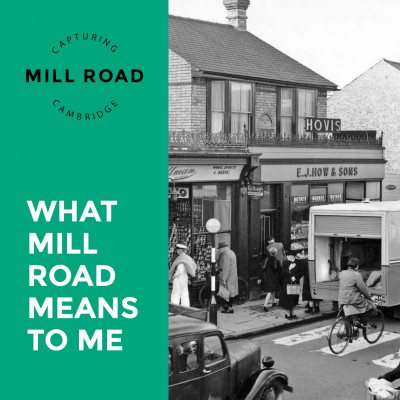

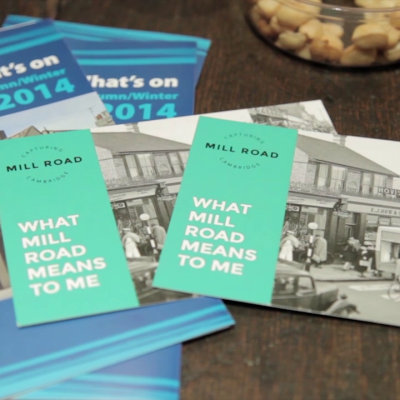

As the side streets were cul de sacs most journeys were via Mill Road, and on foot, which led to a familiarity amongst neighbours. Mill Road was the central meeting point where residents would meet on their way to work, to the shops, or to school. By 1921 Romsey had a population of 7,000 and between the bridge and the end of Mill Road there were butchers, sausage-makers, fishmongers, bakers, a timber merchant, grocers, household furnishers, hardware stores, drapers, hairdressers, boot repairers, milliners, and a cycle shop. Other corner shops could be found in the side streets.

This was a self-contained world ‘over the bridge’.

More Information

- Read A Community in Transition – Romsey Town, Cambridge 1966-2006 as a PDF

- Read the entire Bring It All Back Home: Changes in Housing and Society 1966-2006’ as published

- A Guardian article about the launch of the report

- Read the complete Alison’s Story

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0