Search by topic

- archaeology

- Building of Local Interest

- charity

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- Listed building

- Mapping Relief

- medieval

- oral history

- poverty

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

Courtesy of Suzy Oakes

Courtesy of Suzy OakesWhy Mill Road matters to an historian

Jon Lawrence explores social change in post-war Britain

For ten years across the 1980s and early 1990s I lived off Mill Road, mostly in Romsey, where I eventually bought a house in time to be caught in the early nineties property crash, but also briefly on Kingston Street, where, as an impecunious graduate, I lived in a cellar-cum-‘games room’ with no natural light, no door and no games (it was probably illegal). Like most people, I was mainly drawn to Mill Road by its vibrancy and its alternative atmosphere – it felt more real than the university which had been my main institutional home since 1980. But as an historian then working on nineteenth and early twentieth century Britain, I was also drawn to Mill Road by its history, and especially by the ways in which it seemed to convey a sense of civic identity and pride that existed independent of the university. This was nowhere more evident than in Romsey Town, where trade unionism and Labour politics had put down their deepest roots between the wars, helping to fuel the vivid stories of ‘Red Romsey’ that some of my neighbours could still recount fifty years later: stories about local working men giving their free time to help build the Labour Club on the corner of Coleridge Road or about the celebrities of Labour politics who had visited the ward. They were stories which resonated with pride about having carved out an identity for Romsey that owed little or nothing to the colleges and university that had dominated the wider city for hundreds of years.

Of course things are never that simple – many people in Romsey would have depended on the colleges or university for their livelihood, and much of the land and property would have belonged to Cambridge colleges, particularly on the city side of the railway. But in many ways this makes Mill Road more interesting – we can map the extent, and the limits, of university influence as these changed over time, and as they varied from Peter’s Field at one end to Brookfields at the other. But there is much else that this exciting community history project can hope to tell us over the next few years. The streetscape of Mill Road is varied and ever changing, and this project can help us all to read the layers of the past that surround us – it can also help us to understand what these layers of history tell us about our own society. Ditchburn Place, opposite the junction with Tenison Road, is a case in point. When it was built as the Workhouse in 1838 this would have been the very edge of the city – somewhere that the poor and destitute could be hidden away from respectable townsfolk. Much later, in 1948, when the poor had become full citizens with social as well as political rights, it became the Mill Road Maternity Hospital, a local flagship of the then new NHS. And when the Maternity Hospital transferred to Addenbrookes with the opening of the Rosie in the early 1980s, strong pressure to turn the site over to private developers was resisted, and instead it was converted into the sheltered housing complex it remains today.

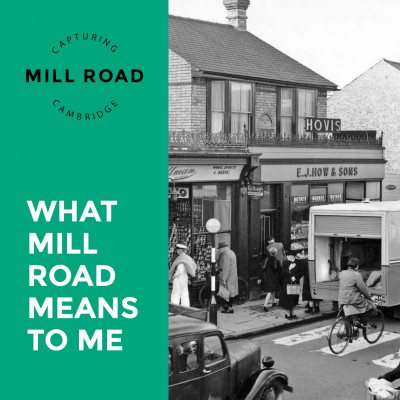

Other public buildings tell equally dramatic stories of change – the GPO sorting offices that are now luxury flats overlooking Peter’s Field, the old cinema that is now a pair of take-aways opposite St Barnabas Church, or the chapel that is now a mosque. But it’s not just public buildings that have changed – the neighbourhoods of Petersfield and Romsey which run off Mill Road have also changed dramatically in the last fifty years. Romsey was never as dominated by railway workers as myths about ‘Red Romsey’ might suggest, but it certainly was strongly working-class in character. This is much less true today. Its long streets of terraced houses, most of which continued to be rented down to the 1950s, are now dominated by young professionals priced out of more central districts. Mill Road’s streetscape is testimony to the demographic changes of recent decades. Its new cafes, restaurants and delicatessens reflect the changing tastes (and budgets) of local residents, including many who have come to Cambridge from across the globe. Perhaps most striking has been the proliferation of ethnic food shops providing the essential ingredients for a myriad of world cuisines. This is not just a local story – people come from all over south Cambridgeshire to shop on Mill Road, but it has undoubtedly added to the distinctively cosmopolitan feel of the street compared with most of the rest of the city.

This project offers a unique opportunity to tap the resources of the local community to understand these processes of change. But we will need to recognise that some people will have experienced change in terms of loss – the disappearance of familiar landmarks and faces that once defined their sense of ‘belonging’. Such feelings are natural and should not automatically be read as a rejection of newcomers from different class and ethnic backgrounds who are no less keen to feel a sense of ‘belonging’ in their adopted home. The tantalising opportunity which a project such as this holds out is the chance to integrate these different visions of place – the chance to help construct an historically rich sense of Mill Road which will allow all its residents to feel connected to the place by a powerful shared story of ‘belonging’.

Jon Lawrence explores related questions about social change in post-war Britain in a half hour BBC radio programme available to listen at http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b045z7s8.

Jon Lawrence, Reader in Modern British History, University of Cambridge

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0