Search by topic

- archaeology

- architecture

- bricklayer

- Building of Local Interest

- carpenter

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- listed building

- medieval

- oral history

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

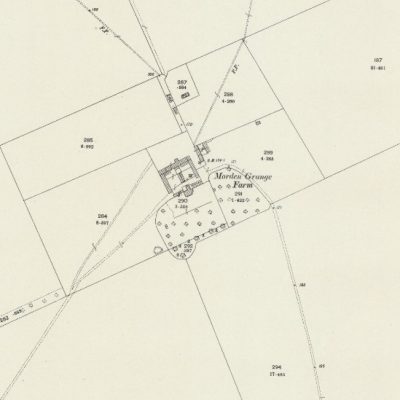

Moco Farm, Steeple Morden

History of Moco Farm

Enid Porter wrote about the ghost and murder at Steeple Morden in Cambridgeshire Customs and Folklore p156f:

In Steeple Morden, on Cheyney Water, used to stand some cottages, now in ruins, which once formed the old farm house known as Moco.

She retells at length the story of the murder of Elizabeth Pateman who was interred in the Parish Church of Steeple Morden in 1734. On her tomb were carved the implements used in her killing – a pea hook, a knife and a coulter.

1901 The CDN 3.1.1901 reported:

The visit of a ‘ghost’ to the cottages of Steeple Morden, known as ‘Moco’ and occupied by a gamekeeper and his wife and a shepherd, has caused a great sensation in the village. A fortnight ago the gamekeeper heard strange noises, as from a person in agony, emanated from the party wall. He then heard a thud and the firing of a gun in one corner of their room. It is stated that one if not two murders were perpetrated at this place many years ago.

Shepherd Rule of Moco Farm moved here after WWI. In 1901 Charles Rule was a shepherd living on Barley Road, Little Chishall, aged 32, born Radwinter, Essex. (Email AN 2023)

In 2022 SR sent an email based on the account heard from his grandfather and his father, William Charles Robinson (1930 – 2015), of those who lived at Moco Farm:

My grandmother, Alice Emma Rule (b. 25/7/1900 at Littlebury near Saffron Walden) moved to a cottage at Moco Farm just before the First World War (c. 1913). She was one of a family of five; together with an older brother Fred and younger sister Nellie, they moved from Great Chishill.

Charles Rule, her father, was a shepherd, and was always known as Shepherd Rule even by his wife and family. He was born in 1869 and, like his family, was connected to the local chapel. They had moved to Chishill as a direct result of Shepherd Rule sticking to his principles. Fred, his son, wanted to do an apprenticeship as an engineer and found a place in a local company ready for when he left school. Shepherd Rule’s employer wanted the boy on the farm and issued an ultimatum “Either the boy comes to work on Monday or you go.” Shepherd went, losing his tied cottage.

Moving to Moco, they soon realized that the cottage felt “strange.” They lived in one half and the other half was then empty as was the farmhouse. It was bleak, isolated and lonely out in the fields. It wasn’t until the war that it became stranger still; footsteps would be heard walking down the passage and they looked up, thinking Fred was home from the Army. He wasn’t; there was no one there. The footsteps were a common occurrence and always seemed to stop at a certain point.

Shepherd wanted to get to the bottom of this and, enlisting the help of a friend, examined the structure of the house where the footsteps always stopped. Something didn’t add up and they began to open up a hole in the wall that sounded hollow. They soon uncovered a recess or small room that hadn’t been opened before. Nothing in it. They left and went to bed.

Later that night Shepherd was woken by a fearful pressure across his throat. It stopped after a while but there was, nor had there been, anyone there. Talking to his friend the next day, he discovered that the same had happened to him, at exactly the same time.

They never discovered what “it” was (always known as “it”) but from that day onwards there were no more footsteps. Shepherd claimed in later life that he didn’t know the history and only discovered it from talking to others.

After the war the family moved to Bassingbourn where Alice met my grandfather and after an eleven year engagement, they married in December 1929. My dad was born a year later and would become the 8th direct generation of farm labourers of the Robinson family of Bassingbourn.

My dad, who knew Shepherd well, described him as a good man, honest and truthful with no reason to make up a story.

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0