Search by topic

- archaeology

- Building of Local Interest

- chapel

- charity

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- Listed building

- Mapping Relief

- medieval

- oral history

- poverty

- Public House

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

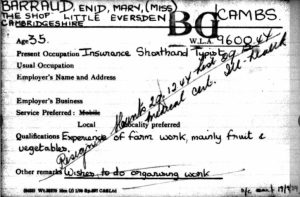

E. M. Barraud

History of E M Barraud

This may have been the location of the cottage in which E M Barraud (Enid Mary Barraud 1902 -1972) and Bunty (Dorothea Rosalind Haines) lived when they worked as landgirls in Little Eversden as recorded in her autobiography of the period, Set My Hand Upon The Plough (2024). A photo of Bunty arriving home with her bicycle shows a large barn on the other side of the road.

Official documents only show her address as The High Street; on her landgirl registration card The Shop is presumably a postal address.

When her first farm let her go because some Italian POWs had arrived, she went to work in the farm opposite the church.

E.M. Barraud and Life in Little Eversden

Enid Mary Barraud (1904–1972), known as E.M. Barraud, was a writer, poet, and journalist whose memoir “Set My Hand Upon the Plough” (1946) provides one of the most vivid portrayals of life in rural Cambridgeshire during and after the Second World War. Living in the small village of Little Eversden, she documented her transformation from a London office worker into a member of the Women’s Land Army (WLA) and a committed village resident. Through her writing, we gain a rare, authentic glimpse of village life from a woman who both laboured and belonged within her rural community. Barraud moved from London to Cambridgeshire in 1939, exchanging clerical work for the physically demanding life of a farm labourer. Owning a cottage in Little Eversden gave her a sense of permanence and belonging. She observed that having her own home made her feel truly part of the “rural scene,” unlike many Land Army women who were billeted and remained outsiders. The cottage—shared with a friend and complete with garden, cat, and dog—symbolised her rootedness in local life. Her reflections on the village library service reveal how culture and learning persisted even in remote areas: she described the joy of reading and gratitude for “the really excellent service our country library gives out in the wilds.” Barraud’s descriptions of work on the land are frank and unsentimental. She learned to milk cows, thatch ricks, and manage daily agricultural tasks, often under harsh conditions. Her prose captures both hardship and pride. She wrote of being physically transformed—“two stone lighter, sun-bleached hair, and hands rough and horny”—and admitted she could never return to the anonymity of city life. Yet she was also aware of economic inequalities: farm wages were a fraction of what she once earned in an office. Her writing exposes the undervalued nature of women’s rural labour and the social divide between agricultural and urban workers. Community life in Little Eversden was central to Barraud’s experience. Her accounts convey the rhythms of village society—the shared work, gardens, animals, and companionship that made life bearable. She valued having a “stake in things,” believing that belonging came from living, working, and investing emotionally in a place. Her letters reveal a balance of independence and community, as she and her housemate managed their own affairs and became integrated into the fabric of village life. Barraud’s eye for nature imbues her work with sensitivity to the rural environment. She evokes the hedgerows alive with thrushes and blackbirds, showing her intimacy with the Cambridgeshire countryside. She also foresaw changes ahead, lamenting the effects of agricultural intensification and the loss of traditional rural rhythms. Her writing bridges the transition between old and modern farming life, capturing both its beauty and fragility. E.M. Barraud’s memoir stands as a landmark in women’s rural literature. It presents Little Eversden not as an idealised village, but as a living community shaped by war, labour, and belonging. Her story reveals how wartime necessity created unexpected opportunities for women to root themselves in the land and find meaning in the everyday work of sustaining it. (AI 2025)

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

Licence

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0