Search by topic

- archaeology

- Building of Local Interest

- charity

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- Listed building

- Mapping Relief

- medieval

- oral history

- poverty

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

George (and Star) Hotel and Whyle’s Malthings, Whittlesey

History of George Hotel

This was the site in 1863 of the murder of Elizabeth Brown by John Green on 12th March.

Cambridge Independent press 9.1.1864:

THE WHITTLESEY MURDER. Execution of John Green. Two Years and four months have now elapsed since Augustus Hilton paid the highest penalty of the law for the murder of his wife at Parson Drove, in the Isle of Ely. It was greatly to hoped that that would have been the last execution at our County gaol. Unfortunately, however, the Isle Ely has provided another subject for the gallows, in the person of John Green, a young and married man, not yet 25 years of age, who was found guilty at the recent assizes of the murder of Elizabeth Brown, whose life he destroyed early on the morning of the 12th of March, in a malting at Whittlesey. It will be remembered that the Cambridgeshire March Assizes fell so soon after the murder that Green was not arraigned on that occasion. At the following July Assizes, a true bill was found against him, well as against Smedley as an accessory; but Mr. Metcalfe, Green’s Counsel, applied to the Court for the postponement of the trial, on the ground that the prisoner had not had sufficient time to prepare his defence. Judge Wightman, who presided in the Crown Court on that occasion, had no hesitation in granting the request. It was but just that the application should be complied with. Every prisoner—more specially when his life hangs upon the issue of the trial—should have every facility given to him establish his innocence, if he be able; and, therefore, John Green had ample time and plenty opportunity to rebut the grave charge upon which he stood arraigned. Several months have elapsed since the prisoner’s counsel asked for an extension of time to prepare bis defence ; but this fact must be borne in mind that Mr. Metcalfe at the trial made no defence. The principle acted upon reminds us of the wellknown anecdote of a lawyer’s brief to his barrister “No case ; abuse the other side.” Not a witness was called; but surgical evidence was ridiculed ; the police and magistrates’ clerk were subjected to that irony and those bitter complaints which are the prerogative of the Bar, but at the same time the contempt of the more intelligent portion of the community. The police were by the learned counsel accused of over-zeal. But when it was discovered that a dreadful murder had been committed ; when circumstances presented themselves that fastened suspicion upon John Green; that he was last seen in company with the deceased ; and on the morning of the murder was seen hurrying, in disabille, away from the spot where Elizabeth Brown had lost her life, the police would not have done their duty if they had not pursued their inquiry with zeal, industry, and perseverance. They did so, and for which society owes them thanks; if they had been negligent in their duty, fearing to be carried away by ” over-zeal,” they would have merited and received the odium due to inefficiency. The man who slew Elizabeth Green was hunted down. The police were, from the first moment after they knew of the dreadful deed, on the alert. They never relaxed in their efforts till the case was made full and complete against the murderer; and in the history of murders, perhaps there never was a case, dependent upon circumstantial evidence, more complete; not a link in the great chain was missing. The direct evidence of witness seeing the murder was wanting ; but the train of circumstances which brought home Green’s guilt of killing Elizabeth Brown, were of the completest character ; of a description, in fact, which no intelligent jury, anxious to their duty, could resist, terrible as was the ordeal under which they were placed.

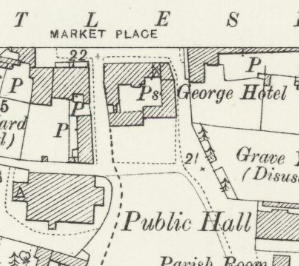

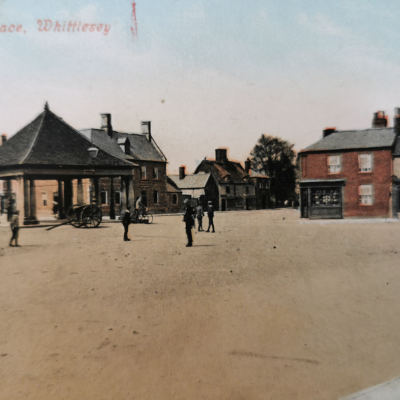

On the south side of the Market-place, at Whittlesey, there is a square block of buildings, with a carriageway all round. The northern half of this block is formed by the George and Star Inn, the principal front of which looks into and forms part of one side of the Market-place; the southern half of this block consists of Mr. Whyle’s malting and premises, which are constructed that the buildings themselves form the boundaries of the property, therefore the George and Star yard, and the Malting yard, are in the centre of this area so circumscribed by buildings.

The Inn yard and Malting yard are separated by an old brick wall, 6ft. 9in high; the wall on the Inn side has been battered by skittle playing; thus it is a very easy matter to put one’s feet into the holes in the wall and scale it. A short time before the murder, a wood fair had been held in the town, and some cow-cribs, field gates, and pieces of timber were stacked against the wall on the Inn side, forming in reality a kind of staircase; while on the Malting yard side an empty kilderkin was placed on end, touching the wall; so that by stepping up the cow-cribs, etc., in the Inn yard, over the wall, and down on the other side to the top of the kilderkin, and thence to the ground, a very easy path was formed between the Inn yard and the Malting yard. The outer gates of the Malting yard were doubly locked, by the day lock, of which the prisoner had the key. and by the night lock, the key of which was of course kept by the master. The Malting was entered first by a door leading from the yard into the coke-place; this door Smedley purposely left unlocked. This coke-place forms the porch, so to speak, of the building, a doorway leads from the coke-place to the chamber, or room containing the furnace and kiln for drying the malt. In the furnace room is a deeply receased window, in the thickness of an old thick wall, the window sill is broad, and contains a desk and writing materials for the use of the excise officers and for book-keeping; upon this sill the prisoner placed the basket-bottle of gin referred to in his confession. Between the window sill and the floor is a strong fixed seat or settle (opposite to the furnace door), 10ft. long and 13in. wide, used by the man man who is tending the fire, and often used for putting wet sacks upon so that they may speedily dry; above the settle are several hooks in the wall, upon which the malting men hang their coats, etc., while at work.

At the end of the furnace room (opposite to the entrance door) a door leading to the floor of the Malting, on which the steeped grain is laid to dry; it was against this last named door that the body of the deceased fell; this door was very much burned, as well as the settle, and sacks. Smedley, our readers are aware, was acquitted of all participation in the murder, or, indeed, of having any knowledgo of the fact. It is due to him to repeat what the Judge said on his trial, that “he had no more to do with it than (the Judge) had.” This remark applies of course to the murder, and to the charge of his having harboured, or attempted screen Green ; but by a confession made by Green, Smedley was aware (if Green’s statement is to be credited) that Green had stolen a bucket of gin from the George and Star public-house, and secreted it in the malting, where the murder was committed. Notwithstanding that the above facts were elicited the trial, it was the belief of many persons that not only was Green innocent, but the confession which Green made, on the Tuesday subsequent to his trial, shows that the Jury had exercised great discrimination. It would appear that Green had not made a confidant of his solicitor; or it is very probable that the defence would have assumed a very different aspect. As it was, Green’s counsel argued throughout that Green was never in the malting with Elizabeth Brown; that she by some means obtained access to that building, fell down in a state of intoxication, and was accidentally burned to death, thus becoming the victim to her own folly and intemperance.

Against this plea we have the fact of his falsehood as to his being in bed by half-past 11 o’clock on the night of the murder, whereas it was indisputably proved by the woman Macdonald. that Green was seen with Elizabeth Brown at half-past one o’clock, going to the malting; that she invited Macdonald to accompany her; she refusing, saying “One woman with one man is quite sufficient.” Then we have the testimony of Green on that night wearing a peculiar cap, which was found in the malting the next morning, before he got to the building when he was sent for, and several persons seeing him just before six o’clock that morning, running in an excited state, without a cap, his clothes in disorder, towards his own home. This is followed up by the testimony of his next door neighbour, who states that he heard Green rush in his own house, upstairs, and high words taking place between Green and his wife. Green has, since his condemnation, admitted that his wife, on his arrival home, bitterly expostulated with him for remaining out all night. Then, again, there was Green’s scratched face, scorched trousers, and burnt hair, and his carrying about him the same peculiar and offensive smell which proceeded from the black and charred remains of the dead woman. In the face of all this and other evidence, Counsel’s arguments to show that Green was not in the malting with his victim, completely fell to the ground, and the plea of Accidental Death could never find favour with any Jury.

Now, if Green had made a full and free confession of the facts in the first instance —on the morning when he was taken into custody—a defence, grounded upon Manslaughter, would have been fair, natural, and for aught that can now be said, successful. Nobody believes that when John Green invited Elizabeth Brown to accompany him to enjoy a carousel over his stolen gin, that he had the remotest intention of murdering her. No doubt at that time he was on the best terms with her. Indeed, he has admitted that previous to his accompanying her to the malting, he had gratified his unbridled lust upon ter. It was when he commenced his importunities in the malting, and when, too, he was rendered savage by resistance, that the dreadful act was done, for which he has paid the penalty. The conflict must have indeed, been terrible; both powerful in strength; both maddened by drink; both resolute and determined to obtain the mastery. Had she not resisted, she would in all probability have been alive at this moment; at any rate, she would would not have been murdered by her paramour. Nothing surely could surpass in horror the scene that was enacted in that malting (for ever rendered notorious, like the Red Barn of Polstead, in which Corder murdered the unsuspecting Maria Martin, now some 40 years ago) on the morning of the murder, and after its perpetration. A violent blow from the hand of the drunken ruffian had felled his victim to the ground ; she appearing insensible he kicked her with such force as to break her ribs. With repeated kicks he spoke to the woman, and at length obtaining no answer, he picked her up, and to use his own words ” I found she was dead! !” He gave no alarm; he obtained no assistance; he supposed she was dead. He was mad drunk and frightened, and therefore unable to distinguish between Death and Insensibility; and in proof of his ignorance and brutality, he determined upon adopting the horrible course of destroying the body by fire, to cheat justice, as he thought, and escape the suspicion that Elizabeth Brown died by his hands. For this purpose he staggered around the building, and collected a number of sacks, with which he covered the body, and with the ashes from the malt-kiln he produced a flame, and as it increased in extent, he stirred up the burning sacks, the better, as he thought, to finish his task. At length, overcome by his drink and excitement, and the heat by which he found him-self surrounded, he sunk upon a seat, and slept, while the body of his victim was becoming a charred and frightful spectacle. At length, the sleeper was aroused by a sense of suffocation, and on gazing around him the horrible reality of the deed he had committed burst upon him, and, forgetful of his cap, he rushed from the spot, slamming the door after him with great violence, and he was seen rushing towards his home by several persons well acquainted with him. In the minds of many thousands of persons in this county, there is a very strong feeling against Capital Punishment; indeed, to such an extent does this feeling exist, that they would sooner murderers escape punishment altogether than that the gallows should be resorted to. We have quite sufficient evidence of this by the fact that several of our daily metropolitan journals devote their ability to prove that the evidence produced against the criminals is insufficient to warrant the verdict arrived at by the jury; we might illustrate the case of Dr. Smethurst and others, who, after their condemnation, have been set free ; whereas if death were not the punishment, efforts would have been made to save the murderer. If the evidence be too clear to admit of any doubt, then the plea of insanity is resorted to, and the Secretary of State is overwhelmed with memorials to stay execution; as in the case of Townley, for the Derbyshire murder, who is now respited ” during her Majesty’s pleasure”—wholly owing to the fact that many thousands of persons have memorialised the Home Secretary to stay execution on the ground that he is insane. Yet, strange to say, not a voice has been raised to prevent John Green from dying by the hands of the public executioner; and yet the same arguments advanced to save Townley from the hands of Calcraft might, with the same justice, have been used for Green; for, whatever may be averred to the contrary, Townley’s was as deliberate a murder as was ever perpetrated, while no malice aforethought can, by any possibility, be attributed to Green. Townley made a purpose journey to destroy the life of Miss Goodwin, and inveigled her from her house, while Green never knew that his victim was dead until he lifted her up, and found that the vital spark had fled. We are convinced that this matter will be most severely commented upon by tho public press. It does not look like evenhanded justice. There is, however, a great difference in the position of the two men ; and an equal difference in the facts relating to their several crimes. With regard to Townley’s case, there was something of romance about it. Townley loved his victim to distraction. They had plighted their troth. They were under an engagement to marry. Both moved in a most respectable circle; but she discarded her ardent admirer, and transferred her affections to a fascinating young curate. Townley became frenzied at the intelligence, and sought interview with the false fair one; he obtained it; he had provided himself with a knife of large dimensions; he expostulated with her in her father s garden ; she was resolute, and the villain plunged his knife in the throat of his victim; he did not seek to destroy her body by fire; he did not fly appalled at the act he had done; on the contrary, he gave the alarm; helped to carry his victim into her father’s house, which she had so recently left in high spirits and in good health; and, on being expostulated with by her grandfather, said ” I killed her. The woman who deceives me dies. She knew my temper.” This sounds romantic; and the cry is ” He loved her tenderly ; and love and disappointment have turned his brain. It would be cruel, indeed, to hang him.” Then ”mad” doctors came to his rescue, and put forth unintelligible jargon as to his ignorance; his want of preception of right and wrong, etc.

Now take the of John Green. He was a poor, uneducated laborer, when he killed Elizabeth Brown. He had scarcely heard of a future state of existence; he was head-strong, violent, and given to the gratification of all the animal passions; his lust met with unexpected resistance; he beat the woman he had been fondling with ; he kicked her to death, not knowing that he had done so; and then was ignorant and mad enough to imagine that he could conceal his guilt by burning the body of the dead woman, at the time he did so being drunk with swallowing plentifully of raw gin, which he had stolen. This was low and brutal murder, there was nothing of romance in it; and sickly sentimentality, for the nonce, could not be awakened even in the minds of those for whom the gallows has such repulsiveness. The magistrates at the Derbyshire county sessions have expressed their disapproval of the respite of George Victor Townley. They assume that he is not insane, and upon that assumption base their demand for his execution. This demand was made in the shape of a remonstrance addressed to Sir George Grey, which was adopted at the sessions Tuesday. We have another case, however, in which the the anti-hanging society is laboring to save a murderer from his well-merited fate. Samuel Wright is a bricklayer, in London, uneducated, ignorant, and violent; he lived with woman (to whom he is not married), she, however, has highly respectable connections, she bad the advantage of fine education but she is ” a fallen one,” and becomes the paramour of an ignorant, low-minded fellow. He became jealous, and a few nights ago he went home, and cut the woman’s throat; he is caught, if not in the act, at any rate blood-handed. His exclamation was ” It is no use denying it, I did it. There is no hold for it.” He is taken into custody before he can leave the room of horror; within a few days he, at the Old Bailey, pleads guilty. He presists in his plea. He feels that it would be perfectly useless to resist his seemingly inevitable fate; but this monster has more friends than he dreams of. He little thought that the Editor of the Morning Star, the great anti-hanging champion, would come to his rescue, but such is the fact. That journal states that the trial was too premature; no time for defence, &c. &c. Why the man admitted his guilt; no trickery, no subterfuge, no impassioned eloquence, no plausibility, no legal quibbles could avail Samuel Wright; yet common sense is outraged by an impassioned appeal on behalf of a murderer, caught in the very act of his atrocity, on the ground of prematureness of trial. With the ignorant and the morbid, the wicked and the reckless, such Star arguments may find sympathisers ; but not with the intelligent public. We find, however, that the Secretary of State has deferred execution for several days; and the Star adds, we hope that his execution is altogether abandoned. Then why was Green executed ? Let there be fairplay, even with the gallows, At any rate, no one has been insane enough to put forth the plea of insanity for Wright.

The prisoner throughout the trial which, it will be remembered, lasted two days, never anticipated an adverse verdict. He did not hesitate to state on the second morning of the trial, that he was certain of an acquittal; it was after the Judge had pronounced sentence of death upon him, that he twice emphatically exclaimed, ” I am an innocent man,” smarting, no doubt, from the frustration of his expectation of a speedy release from gaol, and an escape from the gallows, and a return to his debauchery and his wretched companions. It was observed that during the whole of the trial he never once looked at a witness; nor did he appear to take any notice of the proceedings. Whether in his mind he was intently watching the progress of the trial, and the weight of evidence against him was only known to himself. The father of the prisoner was in Court to hear the trial, but before verdict of Guilty was returned, left by timely intimation. He went home by the evening train, and was met at the station by his wife and the wife of the prisoner, and others, they fully expecting the prisoner to come with his father, and had prepared refreshment; but, to their astonishment and dismay, no John Green, jun., came, and a gloom was cast over the whole family circle. The wife of the prisoner, after his condemnation, felt the shock most keenly, and soon quitted the humble ” cot” where many happy hours had been spent. Since the trial efforts have been made by Mr. Wilders, the prisoner’s attorney, to get a reprieve, on the ground that ” no malice or forethought” had been proved, and, consequently, it was not premeditated murder. A letter has been addressed by Mr. Wilders to the Secretary of State, and also one has been written by Mr. Metcalfe, the prisoners counsel, to the Judge, Baron Martin, but without effect. Many persons did not hesitate to express their belief that the prisoner was innocent; at any rate, they urged that the evidence was not sufficiently strong to warrant a conviction. On the following Tuesday, however, the question of his guilt or innocence was set at rest by full confession of the prisoner’s guilt, which has already appeared in this journal. After the publication of the confession, Smedley wrote to Green, denying certain portions of the statement—that, among others, regarding the gin left in the building. Green replied, adhering to the terms of the confession, and mentioned, in particular, about the knife which Smedley lent him to open the door with. Green also explained away (so we are informed) other statements made by Smedley. After his condemnation, Green maintained great calmness of demeanour. With the exception of making his confession, he never alluded to the murder, or mentioned the name of Elizabeth Brown; on other subjects he would talk freely, and tried to improve himself in reading, of which he was totally ignorant before bis incarceration. He cared very little for exercising himself in the yard, but remained in his cell. He ate heartily; his diet not being confined to the ordinary prison diet; he was also allowed the indulgence of tobacco. Green was a very fine young man, of good symmetry, standing just upon six feet high, and weighing 13 stone 3 1/2lbs.; and possessed of great physical strength. Without having bad features, his countenance was very forbidding. His cheek-bones were high; his forehead ample, but receding; his jaws prominent, which caused a slight cavity with the cheeks ; his lips were long, straight, remarkably thin, and quite colorless; he was “smock-faced,” having no whiskers; his hair a dark brown ; eyes grey; but an excellent nose of the Grecian style—completely straight and well- formed; his face oval and pale; yet not by any means of an unhealthy hue; yet, upon the whole, his countenance was forbidding, and ill-temper and strong passions were unmistakeably displayed. The following letters were written for the prisoner at his request, he not being able to write:

Dear Mother, Dec. 1, 1863. In reply to the anxious inquiries contained in your letter of the 5th inst., as to how I how I have spent my time hitherto, I write to inform you that all leisure time has been occupied in reading and writing the Gospel of St. John, being the portion of Scriptures that I most frequently read, and I trust that what I have read will not be vain, but that I may for the time to come live a different life than I have hitherto. I thank you for the different texts of Scripture that you sent to afford encouragement to a penitent sinner. They are, indeed, Gracious promises from Him who has said, ” He that cometh to me I will in nowise cast out.” I trust that I shall soon be restored to my home and family, and that I shall better perform the duties of son, husband, and father, than have hitherto done. Please to send word who will he present at my trial. I am much obliged to you for the 2s. worth of stamps sent me by my aunt and sister. Please to thank them for me, with love to you all, I Remain, yours affectionately, John Green.

Dear Parents, Dec. 21, 1863. with great sorrow of mind that I now write to you, knowing that my hours are numbered, and that I am shortly to suffer the penalty of death for a crime of which I innocent. Let this be your comfort, dear parents, that though your unhappy son has greatly sinned both against God and man, yet he has not that great crime to answer for to his Maker, before whom must all, sooner later, appear. This, dear parents, is my only comfort in this hour of trial, and may the Great God before whom I must shortly stand pardon all sin, and receive me into his Heavenly Kingdom. This, my dear parents, is my daily prayer. I aware that in many ways I have not done my duty to you as a son, and that my faults are great and many, but my conscience does not accuse me of that crime for which I to suffer the last penalty of the law. May the Great God provide for my dear wife and family, and enable you all to bear up under this great trial. May I improve the short time that is left by studying the Scriptures, that my mind be in a fitting state to meet the sad end to which I am condemned. Dear parents, let your Prayers I ascend with mine to the Throne of Grace, that God will in His great mercy receive my soul. So prays your unhappy Son, JOHN GREEN. I hope when you come to see me that you will all come together, and my dear children also. My love to all. [Green made full confession of his crime Dec. 22. The above letter is dated the 21st. Ed.]

Dear Wife, Dec. 26, 1863. I received your kind letter, and was glad to hear from yon all I should like know on what day you all will come to see me I should like to see you and the dear little children. Father and mother, and all my brothers and sisters. I am not in wants of anything as regards eating and drinking. All I wish and pray for now is God’s forgiveness for my past sins. I hope and trust I may some day meet you all in that Heavenly Home where there is no sin nor sorrow. I have got leave for Mr. Keed to visit me as a friend. Give my love to all my brothers and sisters, and all • roy aunts and uncles, with kind love you and dear little children. I remain vour affectionate husband. JOHN GREEN. Good bye, and God bless you all.

The Rev. John Keed, Minister of Zion Chapel, Cambridge, has visited the prisoner as a friend, daily ; and on December 28, wrote to his parents at Whittlesey, as follows:— Dear Friends,—l have not the pleasure of knowing you. I have to-day had my first interview with your poor son, in his cell; and I have engaged to go and see him every day, whilst he may be alive. I was glad to find him ready to listen to what I had to say, and willing taught and read God’s Word (psalm 55 of Isaiah), and prayed with him, and he was much softened, I hope. Still it is an awful position and soon to be before the bar of God. I urged him give attention to this great matter of making peace with God, and being ready to meet his solemn doom. Oh! how fearful is sin, and how dreadful the hardening nature of it.

It is now just 60 years since the County Gaol was erected; and since that period the following executions have taken place :

Bird, for forgery—18l2.

Dawson, horse poisoning—18l3.

Scarr, housebreaking and arson—1817.

Williams, for murdering his wife—1819.

Lane, for rape—1824.

Osborne, highway robbery—1829.

Foreman, Reader, and Howard, arson—1830.

Westnott and Carter, for shooting at gamekeeper—1833.

Stallon, arson—1833.

Elias Lucas and Mary Reader, for poison—1850.

Hilton, murder of hia wife—l861.

On Sunday, Dec. 27, the condemned sermon, as it is commonly called, preached by the Rev. Mr. Ventris, from John iii, 14, 15— “And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the son of Man be lifted up. That whosoever believeth on Him should not perish but have eternal life.” The preacher dwelt upon the latter portion of the text, making no allusion to the prisoner individually, but applied the text to mankind in general. The father of the prisoner has been employed by the Great Eastern Company for a number of years as carter of the goods to and from the station, and is highly respected by the inhabitants, a regular attendant at Church, and has done his utmost to bring up the large family of ten children respectably. The prisoner is the eldest of six sons—the others occupying creditable positions in life, and they were all educated as far the limited means of the father would admit. The prisoner was born at Whittlesey, in June, 1838, where he has resided up to the time of the murder. He has been employed by Mr. Whyles, maltster, as a laborer, for several years, and married about six years ago, the daughter of a man named Goodwin, by whom he has three children, the eldest not yet five years old. The prisoner’s father has borne an irreproachable character, and nothing has occurred to throw a doubt upon the honesty and respectability of the family up to the committal of the murder. The prisoner, however, by the police, has been looked upon as a loose character; still, no charge had before this been brought against him. The prisoner used to live in one of a row of cottages standing upon the road leading to the station. The wife and children have, through poverty, been obliged to leave the cottage, and have for a time taken shelter under her father’s humble roof. The prisoner was in a club, and application will made by the father for the benefit of the prisoner’s wife and family, which the father considers his son entitled to. The father and mother occupy a cottage, the very neatness and cleanliness of which bespeaks their habits of industry. The prisoner has a grandfather and grandfather’s brother alive ; they reside in Whittlesey Fen, and are much respected. On Friday night. Green, according to his father’s desire, made an effort to read one of Mr. Spurgeon’s sermons; but it was quite beyond his comprehension; and he read from one or two tracts, which were written with great simplicity. Green never prayed of his own accord; but when a remark was made to him, ” May God have mercy upon you” his reply would be, ” I hope He will have mercy upon me.” He retired to bed at quarter past 11 o’clock, having first partaken of some bread, meat, and ale: during which he said, ” I am just getting over parting with my friends.” He soon fell soundly to sleep, and never woke till 6 o’clock, when he was disturbed by one of the officials, who sat up with him. He then declined to rise, turned himself over, and slept for an hour. On awaking, he said that he had slept very soundly all night; and had never dreamed. He took very little breakfast, and was visited by the Chaplain, who read and prayed to him, and who also administered the sacrament. About quarter before nine o’clock, Calcraft proceeded to the pinioning-room, and adjusted his apparatus, now made of leather, so far as the body is concerned. A few minutes after 9 o’clock, the mournful procession started from the pinioning-room towards the scaffold. The culprit walking first, Calcraft, the Chaplain, the Governor of the Gaol, and the Under-Sheriff following. On arriving on the scaffold the culprit gazed around upon the concourse before him. The Chaplain was by his side, and both kneeled down, while the former read several prayers. These being concluded, Calcraft placed the criminal under the beam, and speedily fastened the rope, then stepping from the drop, he drew the bolt; the drop fell, and the murderer of Elizabeth Brown was dead instantly; a few slight quiverings were all that were perceptible. The body, however, turned completely round, so that instead of facing the Castle Hill, as it did when it fell, it turned round towards the gaol doors. Previous to going up the gallows, the hope was expressed to him that he would meet death with firmness. He replied, ” I hope I shall; I will try.” In that trial he was quite successful, for, to all appearance, while he was on the scaffold, he maintained the greatest self-possession. The proceedings on the scaffold did not occupy three minutes ; and by ten minutes past nine the culprit was dead. It will, probably, gratify the curiosity of some persons, to know that the fall of the rope is just six inches. As usual, the body hung for an hour, and at four o’clock it was buried by the side of the remains of Hilton, the last murderer, who suffered at the Cambridge County Gaol. From the Governor, and all the gaol officials, the unfortunate man received every kindness consistent with his position, and for which, we understand, he expressed his thanks. Many thousands of persons arrived in Cambridge after the execution had taken place; throughout the day the public-houses were thronged, and we are sorry to say that good deal of drunkenness was the result; indeed the police state that they never saw so much.

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0