Search by topic

- archaeology

- Building of Local Interest

- charity

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- Listed building

- Mapping Relief

- medieval

- oral history

- poverty

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

Mark Taylor

Mark TaylorReflections on a Personal Disability History by Mark Taylor

Access Officer for Cambridge City Council and South Cambridgeshire District Council.

I am Access Officer for Cambridge City Council and South Cambridgeshire District Council. I try to ensure the service provision of both councils is as accessible as possible. I working in the planning department and advise on access issues in the built environment. I give advice on the Equality Act. This is my story:

Thinking back to my childhood I can remember lots of inappropriate jokes about disabled people. I would laugh at jokes which must have been hurtful to other people. Not that I think I was especially mean, but disabled people were treated as ‘the other’ and were people to be pitied. My father was a Baptist minister and some older church members had disabilities, they may have odd looking medical equipment in their homes, may talk strangely or you may just hear their name, but never see them. One church member had a daughter with cerebral palsy a friend had a cousin with the same condition, but as a child you never wanted to have the girl in anything you did at Sunday School and we chose not to include the cousin in any of our play. On the high street in our small town there was a house with several people with learning difficulties and as children we would rush past the ‘looney’ house. In those days disabled children were not included in mainstream schools, but were taken off to special schools by minibus. And so disabled people were ‘scary’, because they were seen as different and not a general part of life.

Not that I had no understanding of disability – I remember my mother had a colleague who was blind and had a guide dog, and my school had a unit for deaf children, who were bused in from all round the county. Even in what should have been a supportive environment the deaf children had their voices mimicked by others. However, when a new deaf student called Mark arrived his great ability at sport won him acceptance by our class – it seemed disabled people had to ‘prove’ they were ‘normal’.

Television did try to make us more enlightened, Joey Deacon, who had cerebral palsy, or someone whose disability was caused by Thalidomide would be brought onto to Blue Peter to talk about their lives. But, in my school it became an insult to call someone a ‘Joey’, a ‘Deaconoid’ or ‘Flid’ (we didn’t even know the spelling of Thalidomide).

I actually think I had a slightly better attitude to disability than some. Yet ‘fear’, ‘pity’ and ‘contempt’ were part of my feeling. I was, compared to now, misogynist, racist and homophobic and we would use multiple insultstowards these groups that would be too controversial to write here now, yet all these terms were used daily, by the television sit coms of the time, by newspapers and in playground talk.

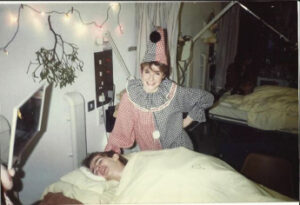

I went to college in 1985, had my 20th birthday and when playing rugby for the college team managed to have a spinal injury leaving me paralysed in all my limbs. Within a week I was at Stoke Mandeville hospital, at the National Spinal Injuries Centre, it had an international reputation of excellence and I had no doubt I would be restored to the normal world.

I met Jimmy Saville, Noel Edmunds, John Entwhistle of the Who, Frank Williams, Norman Tebbit’s Wife, Cheri Gross, the diver who saved Simon Le Bon, a leader of a Hell’s Angel chapter and others. Stoke Mandeville was odd, everyone motivated, wheelchair use almost glamourous (depending on the brand of chair), and local shops and pubs were used to groups of wheelchair users. All the motivational speakers had spinal injuries, moved into the area, married a nurse and worked for a disability charity. I didn’t object to marrying a nurse, but I had no wish to live there or work with disabled people before my accident and had no wish to do so now.

Starting to go home was odd, we lived in a run-down Victorian villa that came with my Father’s job. It had flat access and I used my father’s reception room as my bedroom and my old upstairs bedroom became the reception room. However, my local pub was up 2 steps, the rugby club bar up a flight of steps, and friend’s homes were up steps numbering 2 to 20. Initially this was ok as I had plenty of young strong friends to lift me upstairs. However, I couldn’t go to these places without being in a group and risks were taken carrying me down flights of steps by drunken friends.

Fairly early after my return home I went down a country road from where I could see the fields I played in as a child. It upset me that I could never go to those places ever again.

Key to my ability to do things was having a wheelchair accessible van that took me as a passenger. I spent my £16,000 compensation on this converted Ford Escort, its adaptation of ramp and higher roof made it really obviously a specialist vehicle. No member of my family had ever had a new car and I could have had 2 Saab sports cars for the same price, but I cried the day the car was delivered as it was so obviously a disability vehicle. I had little choice as no buses, trains or taxis were accessible.

With difficulty accessing everything including buildings, places and transport, I blamed myself for having been injured, rather than wondering why things had been deliberately designed to be how they were.

Being patronised, sometimes unintentionally, had to be got used to. One café I went to, the owner made engine noises for me when my wheelchair was moving. At a large restaurant every time my friend pushed me to a table the waiter pulled it away, (I think he thought he was helping), but we ended chasing the table, albeit slowly around the restaurant. In a Spanish restaurant in Britain the waiter spent his whole night swearing about me being in the way in Spanish. My friend who taught Spanish thanked him in a very complicated way, showing she’d understood him. When applying for a student bank account the clerk asked for my name and looked at my carer, I answered, clerk said ‘address?’ and looked at carer, I answered, this went on until she said ‘course?’, I said ‘PhD’, to which the clerk said ‘that must be nice for him’.

I had been at college studying history at Winchester, where they didn’t have facilities for my needs, and I found out that Southampton and Sussex University had the facilities I needed. I went to Southampton and I did my BA and Masters there. Southampton had a really good integrated hall of residence. Then I got the opportunity to do post graduate studies at Downing College, Cambridge. A new facility called Bridget’s opened in Cambridge, which offered accessible accommodation for all the 30 Cambridge colleges, as basically no college had wheelchair accessible rooms. In those days I often had to go very odd routes to lectures, use back entrances to libraries, use good lifts to tutorials and inappropriately sloped ramps to seminars.

I received an award towards my fees from the Snowdon Foundation, a charity supporting disabled people. I went to an awards ceremony in London and on my table was Nicholas Scott, the ‘Minister for the Disabled’. He had a notorious career but was being lobbied by several other guests as the Disability Discrimination Act was in an early stage. At that time it was something I was barely aware of.

I then received a Rotary Foundation scholarship to study in Los Angeles. The Americans with Disabilities Act was still a recently enacted law. Watching the news I found it odd someone was suing his gym as he could only use a side entrance, not the main one. I thought he should be happy for just getting access.

I finished my academic career by applying to Keele University to take a course to teach in further education. I arrived for the interview and they hadn’t read my application as they obviously not realised I used a wheelchair and they had scheduled the interview in an inaccessible room. Afterwards they wrote saying that due to disability I couldn’t do the course. My MP and former lecturers challenged this decision and got me on the teaching course. On arrival they said I could do the theory, but not the teaching practice. I challenged this and did the practice. On my course of 30 students, I was the only person with an Oxbridge degree, and although I applied for many posts I got no interviews and everybody else got jobs.

Since my accident all my plans had come off, but now I felt I didn’t know what to do. It was a very depressing experience. After a year I took a post as a publications officer at Disability Cambridgeshire, producing, books, factsheets, newsletters and webpages for the charity. I hadn’t planned to work with disabled people but now I was. During this time I supported colleagues on the advice line. From this I realised just how many disabled people had their lives made difficult by the lack of transport or being able to interact with their local community.

Since 2001 I have been Access Officer at Cambridge City Council. I take great pleasure in seeing places are far more accessible now and particular joy in helping individuals with an access issue. It is good to see all Cambridge colleges have accessible rooms and that students use the same entrances and lifts to get to places. Since 1995 every building that has had work done on it should meet a minimum of access standards.

In 1987 the BBC made a comedy called A Small Problem, the premise being that short people were an oppressed underclass, and there was a height limit in imperial measurement. However, the limit was changed to a metric height and this meant the protagonist was now defined as ‘Small’. He fought against his reclassification, but the ‘Normal’ people now treated him with the prejudice he had previously treated Small People with. The series was criticised because of what was said about Small People, but I think these critics missed the parody and the point the comedy was making was that prejudice is a stupid thing – especially when you could find yourself in the group facing prejudice.

From having a general attitude of an 80s teenage boy towards disability, to then being disabled was such a great shock. From having never been limited by my environment or people’s attitude towards me, to not being able to go to my local pub alone and having adults treat you as a child, was something so difficult to suffer.

Britain isn’t a perfect place, but from some of my travels I would say it is one of the better places in Europe. Our planning system does try to improve things. The attitude of people towards me is so much better than 35 years ago, I don’t remember the last time I was patronised.

So I think the DDA has done some good. In my work I enjoy the fact that when I arrive on a site visit, the host sees what difficulties I have with their access provision. Though I still have to challenge the statement, ‘well not many disabled people come in here’, by pointing out bad access is why disabled people don’t go somewhere, not that disabled people don’t want to go there.

One thing I’ve learned is that disabled people may be ‘other’ to you, but tomorrow your parent, your child, your best friend, your partner or, even more surprisingly, you yourself could be disabled. Then you will wonder why your house, car, local shop, sports facility, theatre, pub, restaurant, country park and swimming pool isn’t accessible.

I AM Cambridge: Inclusion and Access in Cambridge

Disability History Month: Gathering, sharing, celebrating, campaigning and archiving experiences of inclusion and accessibility in Cambridge. Raising awareness to bring about change through stories, memories, history and the arts.

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0