Search by topic

- archaeology

- Building of Local Interest

- charity

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- Listed building

- Mapping Relief

- medieval

- oral history

- poverty

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

1 Gold Street / 64 Fitzroy Street 1974 (MoC559/74)

1 Gold Street / 64 Fitzroy Street 1974 (MoC559/74)Gold Street

History of Gold Street

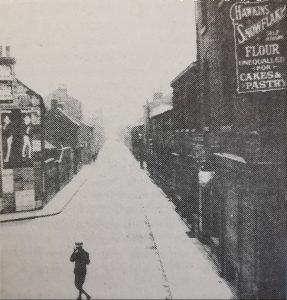

Gold Street was one of the roads that disappeared entirely during the redevelopment of the Kite Area during the 1980s.

This picture shows 50a, 51 and 52 Gold Street, at the junction with Eden Place.

The John Gilpin: the sign for this pub was painted by Richard Leach and is held by the Museum of Cambridge. He painted in circa 1830.

1851

(26)

John Leader, 36, tailor, b Cambridge

Mary Ann, 37, laundress, b Grantchester

Mary Ann, 13, b Cambridge

Eliza, 11, b Cambridge

James, 8, b Cambridge

John Leader married Mary Thompson in Barnwell, 11 Aug 1835. She was the widow of Edward Thompson, the same as the Mary Ann Thompson who married Edward Thompson in 1832.

In 1841 the family were living at 29 Staffordshire Street.

1861

(26)

John Leader, 46, wine merchant’s porter, b Cambridge

Mary Ann, 47, b Grantchester

Mary Ann, 23, milliner and dress maker, b Cambridge

James, 19, E C railway clerk, b Cambridge

Edwin, 12, b Cambridge

In 1871 Mary Ann was married and living at 19 City Road.

(50) The Rabbit

Louisa Kidman, 18, licensee

1864

(50) John Nightingale, brewer

1869

(50) Richard Edwards, b Sawston 1840

1871

(1) Hannah Matthews, widow, 57, dressmaker, b Adington

(2) John Charles Holmes, 29, greengrocer, b London

(3) Leslie Underwood, 40, brewers assistant, b Girton

(4) William Morgan, 54, journeyman, baker, b Bottisham Lode

(5) Samuel Cane, 63, hair dresser, b Essex

(6) William Howell

(7) Sarah Furton

(8) Matthew Langren

(9) Jonathan Kimpton

(10) Martha Green

(11) Thomas Newton

(12) Eliza Beans

(13) Charles Newman

(14) Frederick Reader

(15) George Hicks

(16) William Ward

(17) ‘Johnny Gilpin’

Joseph Farnham, 29, licensed victualler Johnny Gilpin maltster, b Cambridge

(18) Mary Reader

(19) William Walton

(20) Ann Leeds

(21) Mary Ann Lyons

(22) William Baker Pleasance

(23) William Smith

(24) David Chambers

(25) James Preston

(26) John Leader

(27) John Ellis

(28) William Harry

(29) George Smith

(30) John Smith

(31) Jonathan Stinson

(32) James Flacks

(33) Harry Woods

(34) Joseph Ryder

(35) Herbert Mills

(36) Matthew Sparrow

(37) George Clutton

(38) George Scott

(39 – 40)

Edward Baxter Tweed, 29, brewer, b Sussex

Sarah Ann, 29, b Cambridge

Edward Martin, 2, b Cambridge

Harry Tweed, 1 month, b Cambridge

Alice Mary Wallis, 18, sister-in-law, nurse housekeeper, b Cambridge

Elizabeth Berry, 39, widow, monthly nurse, b Cambridge

Rebecca Coe, 15, servant, b Waterbeach

In 1861 Elizabeth Berry was living at 12 Fair Street

In 1881 Elizabeth Samuel is living at 24 East Road

(41)

Edwin Holder, 22, tailor, b Cambridge

Elizabeth Amelia Holder [née Cowell], 25, b Cambridge

In 1861 Elizabeth was at 42 Wellington Street

In 1881 the Holder family were in Carnaby Street, London

(42) George Berryman

(43) George Maltby

(44) William Harry Holland

(45) George Slater

(46) John Hall

(47) Elizabeth Tedd

(48)Thomas Laughton

(49) Edward Newman

(50) ‘The Rabbit’

Richard Edwards, 34, brewer licensed victualler The Rabbit, b Sawston

(51) Mary Hallyer

(52) John Markham

1881

(1)

(2)

(3)

George Field, 77, tailor, b Croxton

Sarah, 71, b Waterbeach

This was the home of their son, Lomas, in 1861. In 1861 George is living at 97 Fitzroy Street.

1880s:

(50) Edwards took over the Fitzroy Brewery associated with the Fitzroy Arms in Fitzroy Street.

1890s:

(11) Brewing business

(50) Edwards transferred brewing business across the road to 11 Gold Street evidenced by 185 ft borehole. Publican of Rabbit is now Henry Nixon who is also brewer.

1891

23

Benjamin Pont, 43, printer compositor, b Cambridge

Catherine Pont, 42, upholstress, b Cambridge

Florence E Pont, 16, dressmaker, b Cambridge

Fanny Pont, 14, assistant upholstress, b Cambridge

Edith M Pont, 11, b Cambridge

Sidney J Pont, 7, b Cambridge

In 1881 the Pont family were at 22 Brandon Place

In 1901 the Ponts were at 13 Emery Street

36:

Henry Hopkins, 64, shepherd, b Ely

Jane, 67, b Ely

Fred, 19, b Ely

Daisy Hopkins, 17, b Ely

John, 11, b Landbeach

Herbert, 3, adopted, b Landbeach

In 1877 the Hopkins family had been living in the village of Sutton in Red Lion Lane. (See ‘The Spinning House‘ by Caroline Biggs, p.155f.) The book narrates that in 1879 Henry Hopkins was the landlord of the Black Horse pub in Sutton High Street. In 1881 the family moved to Potters Lane, Ely. The family, in particular the women became notorious for entertaining men at the hose and in 1886 they wee told to leave. In January 1887 they came to Gold Street. Here the family were watched by Henry Mason, a university Bulldog, as well as Miss Elizabeth Rowley, an officer from the Salvation Army

Daisy Hopkins Cambridge Daily News 3.12.1891

Daisy Hopkin Cambridge Daily news 5.12.1891

Daisy Hopkins Cambridge Daily News Monday 7th December 1891

St James’s Gazette 8/12/1891: THE CAMBRIDGE SPINNING HOUSE CASE. With regard to the sentence of fourteen days imprisonment passed the Vice-Chancellor on Daisy Hopkins, it is now said to a Cambridge correspondent) to have been decided to apply to the High Court lor writ of habeas corpus on the ground that the trial was irregular, and that the evidence did not justify a conviction.

St James’s Gazette 12/12/1891: THE CAMBRIDGE SPINNING HOUSE CASE. DECISION OF THE QUEEN’S BENCH. In a Divisional Court of Queen’s Bench yesterday, before the Lord Chief Justice and Mr. Justice Smith, the Attorney-General (with him Mr. Cohen, Q.C., and Mr. Rawlinson) appeared to show cause against a rule nisi for writ of habeas corpus directed to the keeper of the Spinning House at Cambridge and to the Vice-Chancellor the University to bring up Daisy Hopkins, a girl who had been sent to prison for fourteen days for the offence of walking with an undergraduate, and also against a rule nisi to bring up the warrant of committal that it might be quashed. The Attorny-General in showing cause commenced by citing the charter of Elizabeth, which gave the proctor of the University power to apprehend suspected persons, and the Vice-Chancellor power to order them into custody and keep them there. The powers conferred by the charter had been affirmed by the case of Kemp v. Neville, which also decided that a warrant of committal was not even necessary. Counsel said that when the rule was granted it was said that the charge against the girl was walking with a member ot the university. That was so. But the meaning ol the charge was that the young woman was walking with the undergraduate for immoral purposes. Counsel then read affidavits made by the Proctor to the effect that the young woman was a reputed prostitute, and that she was convicted for being in the company of a member of the university for immoral purposes.

Mr. Justice Smith; How do you get over the fact that this is a court of record, and therefore we can only deal with what is on the record ?

The Attorney-General said that no record was really necessary. All ; the Vice-Chancellor had to do was order her by word of mouth to be kept in custody. That was what was decided by Kemp v. Neville. The suggestion, therefore, that the court was bound by any record was contrary to fact, and the charge even need not have been in writing.

The Lord Chief Justice: You say that the charge was fact that the girl was a woman of immoral character walking with an undergraduate for an immoral purpose.

The Attorney-General: Yes, that was what the charge really was, as shown the affidavits. It was absurd to say that the girl was apprehended and sent to prison for walking in an innocent manner with an undergraduate. That was no offence, and the Vice-Chancellor had no idea of such a thing.

The Attorney General, proceeding with his argument, said the only question for the court was whether the offence of being in the company of an undergraduate for an immoral purpose was an offence which it was within the jurisdiction of the Vice-Chancellor to deal with.

The Lord Chief Justice: It is perhaps a fine point; but if this rule should be made absolute would it be a sufficient return for the Vice-Chancellor to make to the writ to say, I tried her upon a charge which was within my jurisdiction?

The Attorney-General: Most unquestionably, yes.

The Lord Chief Justice: But in point of fact you convicted this young woman for what is no offence.

The Attorney-General contended that was not so, as the charge must taken to be one of being in company with a member of the university for immoral purposes, and he submitted that the Vice-Chancellor, having acted within his jurisdiction, the habeas could not go. As to the certiorari to bring up the conviction to be quashed, he submitted that quashing of the conviction would be no reason for discharging Daisy Hopkins from prison, for the question would arise, Was the charge on which she was convicted within the jurisdiction of the Vice-Chancellor? In conclusion, counsel said he wished to protest, on behalf of the Vice-Chancellor, against the idea that he had ever contemplated sending a young woman to prison merely for walking with a member of the university.

Mr. Cohen, Q.C., having briefly enforced the contention that the Vice- Chancellor, having acted within the jurisdiction conferred upon him by charter, the court could not interfere,

Mr. Poland, Q.C. (with him Dr. Cooper), proceeded to support the rule. He submitted that the Attorney-General had not dealt with the real point at issue. Daisy Hopkins was not charged with any offence known to the law. The charge was reduced to writing, and it was walking with member of the university. She was not charged as person suspected of evil—that was an offence within the charter. It was admitted by the Vice-Chancellor that there was never any distinct legal charge made against Daisy Hopkins. The Vice-Chancellor seemed to have in his own mind what the real charge against her was; but he never gave any expression to it, and the court had nothing to with what was the Vice-Chancellor’s intention but with what was his act. He submitted that, there being no appeal and the court being an inferior one, their lordships ought to be very strict in keeping the proceedings regular.

The Lord Chief justice, in giving judgment, said that, in one point of view this case was one of great importance, yet in another it was of very little importance, the girl, Daisy Hopkins, would in any circumstances only have to undergo a few more days’ imprisonment. As he gave the university authorities credit for having sincere desire to comply with strict legal forms, it was not likely that this particular form would ever be used again. He desired to say in the strongest way that his opinion was, and he thought it would be the opinion of all reasonable men, that the jurisdiction of the Vice-Chancellor in dealing with the moral discipline of the university was most important to be kept up; and, further, that he gathered from what had come out in the discussion of the case that the Vice-Chancellor seemed have been actuated throughout by a sincere desire to do his duty, and to have done it, so far as he understood it, thoroughly well and in a perfectly legitimate and merciful manner. No court in the country, not even the highest, could, however, give itself jurisdiction by saying that they meant to give certain meaning to words which did not in themselves give jurisdiction. Therefore as there was no jurisdiction to try the charge stated against the young woman, the rules must go.

Mr Justice Smith said he had no doubt that the woman was tried upon a charge of immorality, and that she and her solicitor knew it perfectly well; but criminal matter there must be a definite legal charge made, and these grounds both rules should go.

Mr. Poland ; And the prisoner be discharged.

The Attorney-General: To save the costs ot bringing the girl up, we shall act upon the rule.

St Jame’s Gazette 30.12.1891: The girl, Daisy Hopkins, who was concerned in the recent Spinning House case at Cambridge, is about to bring an action against the pro-Proctor for false imprisonment. She claims £1,000 damages.

Miss Daisy Hopkins, amid the applause of sympathetic press, is about to bring an action against the Cambridge proctor. She assesses the damages at £1,000 but we are not informed for what precise injury she claims this sum. If it be for incarceration in the Spinning-house, where she remained for ten days, £100 per day seems just a little excessive, and many of us would be not unwilling to spend a week or so every year in the academic city on the same terms. But if the £1,000 be claimed for slanderous insinuations and groundless charges against the lady’s fair fame, we have no doubt that jury will assess her character at its precise value, and cause the luckless proctor to rue the day when he laid hands on the modest Daisy. Still, it may be observed that the Queen’s Bench granted the habeas corpus simply on the ground that the warrant under which Miss Hopkins was relegated to the Spinning-house was informal, and that the judges abstained from expressing any opinion concerning the lady’s character or avocation.

St James’s Gazette 26.3.1892: The sequel to the Spinning House Case, in the shape of the action for damages brought by Miss Daisy Hopkins against one of the Cambridge Proctors, ended yesterday, as might have been anticipated, in a verdict for the defendant. The question for the jury was whether there had been reasonable grounds of suspicion in the matter, and the evidence clearly showed that there had. Any one who knows anything about University life, and the requirements of University towns like Oxford and Cambridge, knows that special powers for regulating public order and morals are absolutely necessary. The Radical papers have, of course, made great outcry about infringement of the liberty of the subject, as though a frightful outrage had been committed. That is all nonsense, as the result of this case shows. The brief for their side, fully set out in Mr. Murphy’s oration, admitted of a good deal more tall talk than the plain case for the University did; but all the common sense was the other side.

For more discussion see:

Daisy Hopkins and the Spinning House Case – ruling from the Lord Chief Justice. 1891.

1907

(11) Louisa Edwards takes over brewery

(11) Brewery taken over by Wood and Sons mineral water works

1913

WEST SIDE from Fitzroy Street

(1) G P Hawkins, bakers and confectioners

(2) George Mathie, joiner

(3) William Chapman, bootmaker

(4) Charles Buttress

(5) –

(6) Edward Blake, college servant

(7) Charles Ebden, carpenter

(8) Sidney Badcock, carman

(9) Mrs Bell

(10) William Howell, bootmaker

(11) Woods and Son’s mineral water works

(12) William Doggett

(13) William Frederick Evans, college servant

(14) Allen Parker, bootmaker

(15) George Starnell, painter

(16) Mrs Adlard, sweet shop

(17) William George Shipp, The Johnny Gilpin

(18) The Johnny Gilpin

(19) Charles Frederick Connor, tailor

(20) John E Leeds, railway servant GER

(21) Joseph Bailey, cab driver

(22) William Clements, labourer

(25) Charles Whybrow, labourer

(26) William Long, carman

(27) William Johnson, boot closer

(28) Daniel Holmes, wireman GER

(29) John Rice, gardener

(30) Mrs Ludman

(31) William Huntley, fish hawker

(32) George Wallis, coach trimmer

(33) George Turner, labourer

(33a) Nathan Smith

EAST SIDE from East Road

(34) Albert Odell, dealer

(35) Thomas Claydon, theatre employee

(36) Arthur George Kiddy, cement worker

(37) Mrs Mansfield

(38) Mrs Martha Scott, dairy

HERE IS CRISPIN STREET

Star Brewery Ltd

(40) Alfred Henry Goode, Sovereign Brewery Tap

(41) William Farmer, basket maker

(42) George James Hunt, whitesmith

(43) William Shipp

(44) Albert Edward Richardson, labourer

(45) John Laughton, waiter

(46) Charles Smith, lamplighter

(47) John Charles Shadbolt, sailor RN

(48) Thomas Laughton, tailor

(49) William gates, ice cream vendor

(50) John William T Davis, The Rabbit

Eden Place

(1) Mrs Taylor

(2) Henry Bell, groom

Eden Cottages

(1) John Newman, waiter

(2) George Randell Coates, stoker RN

Gold Street cont…

(50a) Charles Darler, bootmaker

(51-52) Mrs Pearson dressmaker

FITZROY STREET

1937 (Kelly’s)

WEST SIDE

(11) Woods and Son , mineral water manufacturers

(11) Frederick Henry Fry, scale makers

(14) Allen Parker, boot maker

(16) Bert Kirkup, cimney sweep

EAST SIDE

Jack Baldry, mineral water manufacturer

(50) Rabbit Public House, Sidney Syson

(51) Charles Darlar, boot repairer

1962 –

1970

WEST SIDE from FITZROY STREET

(1)

(2) John W Cousins

(3) Patrick Sweeney

(4) Mrs K Banes

(5) Edward C Stearn

(6) Herbert S Badcock

(7) Leonard Challis

cont…….

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0