Search by topic

- archaeology

- architecture

- bricklayer

- Building of Local Interest

- carpenter

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- listed building

- medieval

- oral history

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

42 St Andrew's Street: old police station and Spinning House

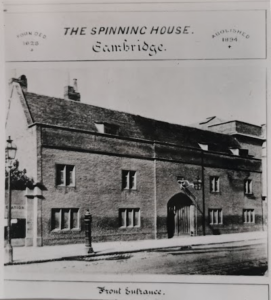

42 St Andrew's Street: old police station and Spinning House42 St Andrew’s Street, Police Station & Spinning House

History of 42 St Andrew's Street

The description of the property in the indenture of feoffment by which Thomas Hobson conveyed the property to the trustees is:

“a messuage and tenement, dove-house and the site of a dove-house, a barn, and all houses and edifices then built upon the farms, gardens, curtilages, courts and grounds thereunto belonging, with all their appurtenances, in the parish of St Andrew, without Barnwell-gate in Cambridge.”

The deed seems to imply that some kind of “poor-house” had already stood on the site. (See Outside the Barnwell Gate, Stokes, 1915)

Yet, it does seem that employment was found at the location specially for ‘combers of wooll’ and the weavers of the town, and that several of the keepers of Hobson’s Workhouse are described as ‘woolcombers’ and ‘worsted-weavers.’ In an old Cambridge newspaper (Cambridge Chronicle, quoted in Cooper’s Annals iv p.441) it is stated that on 3/2/1791, ‘the wool-combers of this place rode through the principal streets in grand procession, attended with flags and martial music, in commemoration of Bishop Blaze.’

The 1831 New Guide to Cambridge has this description:

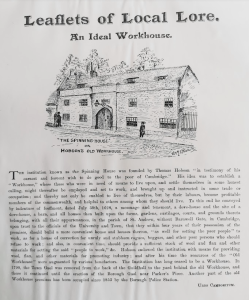

Hobson’s Workhouse, usually called the Spinning House: being a plain brick edifice with stone dressings to the window etc. The interior is divided into wards, after the manner of a prison, it being used for the confinement of disorderly persons of both sexes, committed by the University or town authorities.

This workhouse was founded by the benevolent and eccentric Thomas Hobson, the carrier, who by deed of gift dated 1628, conveyed the site etc to trustees for the erection of a House of Correction, for unruly and stubborn rogues and beggars, and other poor people who should refuse to work, and for providing a stock of wool, flax, and other materials. In 1630, £500 the residue of then money collected for relief of the sufferers by the plague, was appropriated to this building, as were also the rents and profits of Jesus Green, which was to be authorised to be let for ten years, and Hobson, by his will the same year, gave 100l to purchase lands for its endowment, and in 1632 and 1634 the trustees with this and other monies, amounting together to 900l purchased lands at Cottenham, Willingham, Over etc…..

Carter’s History of the County of Cambridge, commenced in the middle of the 18th century, states:

The Bridewell (called by the inhabitants the Spinning House) is pleasantly situated near the fields at the south end of the parish of Great St Andrew’s, and is chiefly used for the confinement of such lewd women as the proctors apprehend in house of ill fame; though sometimes the Corporation send small offenders thither, and the crier of the town is often there to discipline the ladies of pleasure with his whip.

For more information on the Spinning House which was demolished in 1901 and replaced by the police station, designed by architect John Morley, see:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spinning_House

https://www.theguardian.com/science/the-h-word/2012/oct/19/history-science

See also Enid Porter’s article: Proctors and Prostitutes

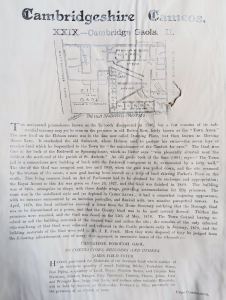

Also on this site for a while was the town gaol. In 1788 the town gaol was removed from the old building adjoining the town hall, called the Tolbooth, a to a newly erected edifice in the old lane now called Downing Place. This building, which stood at the back of the Spinning House, opened by a large gate into the main street, just south of the Workhouse. The new gaol cost the town £911 10s. In 1827 royal assent was given for a new gaol on the south side of Parker’s Piece.

Proposal to turn the Spinning House in Cambridge into a hospital. 1840.

1846

Cambridge Independent Press 5.12.846 account of the inquest into death of Elizabeth Howe:

The coroner was Charles Henry Cooper.

Cambridge Independent Press 26.12.1846:

MUSINGS ON THE UNTIMELY DEATH OF ELIZABETH HOWE.

Inquest of Elizabeth Howe at the Spinning House, Cambridge University’s private prison. 1846.

Cambridge Newspaper slams Cambridge University over the Spinning House. 1846.

1847 7th January

Josiah Chater witnessed the rescue of a girl from the Proctors:

There was a great row in the street this evening with the Proctors. They had taken some girl, but the townsmen had rescued her and were hooting the Proctors.

1851

Edward Willson, 57, keeper of the house of correction, b Cambridge

Elizabeth, wife, 57, matron, b Ely

Hamment [?], grandson, 15, watchmaker, b Cambridge

Lucy, 4, granddaughter, b London

Sarah Tweed, 22, rations labourer or house servant, b Essex

1860 January 13th: The diarist Romilly records in his diary: The Vice Chancellor told me of a capture which the Proctors made at 7 in the Evening of an omnibus on its way to Shelford (I think) where there was to be a dance: the omnibus contained 5 young women and 2 gownsmen (sons of Graham of Hinxton): the females were all lodged in the spinning house: they were not of the lowest class, but one of them had been there before: – the Vice Chancellor has received indignant letters from London saying the girls were innocent milliners going out for a lark …….

Romilly’s editor writes: On 30 January 1860 Proctor Blore received a letter signed by ‘An Inhabitant of the Town’ which led to the stopping of an omnibus near Parker’s Piece before it left for a party at the de Freville Arms in Shelford. Emma Kemp, who had taken her fourteen old sister with her, was then committed by the Vice-Chancellor to the Spinning House for a fortnight, but pardoned after five days as the master of Corpus vouched for the respectability of her mother. This case was to be given wide – and from the University’s point of view – undesirable publicity for many months. Reports in the London press in December and January 1858-9 had provoked protests from parents about the University’s lax reaction to fornication with prostitutes, but now the Town, long suspicious of the Vice-Chancellor’s 350 year-old power to commit to prison ‘common women and others suspected of evil’ arranged for Emma Kemp and Sarah Ebbon, another of the girls, to bring actions for wrongful imprisonment against him. It was the first time the University had been called into court in this matter. the case, eventually heard on 30 November before Lord Chief Justice Erle, was said by one of the Q.C.s opening for Emma Kemp to be ‘of extreme importance to the liberty of Her Majesty’s subjects’. Fitzroy Kelly for the defendant, thought the protection of young men entrusted to the care of the authorities of the University of even greater importance. ……. The jury found that the Proctors had reasonable grounds for suspicion but that the Vice-Chancellor should have inquired into the plaintiff’s character. Damages of £25 were then awarded to the plaintiff, but the Lord Chief Justice stated that ‘in my opinion it is an improper verdict’ and that there must be further discussion since ‘the case is not decided‘.

Those involved in the incident were:

Emma Kemp, 19, 4 Dover Street

Charlotte Looker, mother of Emma, 4 Dover Street

Sarah Ebbon, 5 Adam and Eve Row

Harriett Bell, 20 Adam and Eve Row

Rosetta Aves, 4 Petersfield

Emma Coxall, female refuge Church Street

The report in the Cambridge Independent Press 8th December 1860:

Romilly wrote 12th June 1861: The Vicechancellor was highly delighted at having received a Telegram upon ‘the Proctorial Question’: the Judges having decided in favour of the University on all point: hurrah!

Romilly’s editor writes: the case was at last brought to an end by a tortuous summing up by Lord Chief Justice Erle who decided that the finding for the plaintiff Emma Kemp should be set aside, and a verdict entered for the defendant, and that the same decision must apply to the other parallel case of Ebbon v Neville. However the University had scented danger and subsequently decided to overhaul the procedure in Spinning House cases.

1861

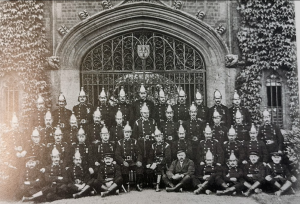

Police Station:

Elizabeth Clark, in charge, 17, house servant, b Oakington

Spinning House:

Agness Johnstone, mistress, 45, matron of Spinning House, b Scotland

1880

1891

Jane (Kate) Elsden, age 17, was arrested 27 January and 11 February 1891 and recaptured 14th February. She was charged with talking to a member of the university, street walking and jailbreaking. She was sentenced to two weeks, then three weeks. At the time Jane was lodging in a room in Kettle’s Yard. For a detailed account see ‘The Spinning House’ by Caroline Biggs (2024).

Cambridge Independent Press 21 February 1891: ESCAPING FROM THE SPINNING HOUSE. Jane Elsden (18) a girl of bad character was charged with having escaped from the “Spinning House’, St Andrew’s street on the 12th inst. From the evidence it appeared that on Wednesday night the prisoner was arrested by one of the University proctors on a charge of “street-walking”. She was brought before the Vice-Chancellor (the Rev Dr Butler) the following morning and sentenced to twenty-one days imprisonment. The same afternoon she escaped from the “Spinning House” from a window in the Chaplain’s room which overlooks St Andrew’s street. She was arrested on Saturday last at her parent’s house in Dullingham. The prisoner, who admitted the charge, said she preferred to be in prison to being in the “Spinning House.” The Magistrates considered that they were incompetent to deal with the case and committed the prisoner for trial at the Assizes. Mr T M Francis conducted the prosecution on behalf of the University authorities.

Cambridge Independent Press 11 April 1891: …. Referring to the case of Jane Elsden, Alderman Balls remarked that her only offence was that she was seen in the street near Christ’s College. She had been incarcerated in the Spinning House and like a stratled hare she ran away at the approach of the proctor and his assistants. Such an incident reminded him of a tale in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” where they were told that the fugitive slave was pursued by blood-hounds, but in this case the unfortunate woman was pursued by the proctor and his bulldogs. Where was the difference? As she said, she had done no harm; she went quietly to gaol, where she was locked up. Then came the trial, if he might call it a trial – a mock trial, a perfect farce; worse than that. He did not wish to say a single word that might be offensive to the University.

In July 1891 Jane Elsden was reported to a resident of Brown’s Yard and to have attacked a woman named Mary Ann Bird. See Brown’s Yard.

Daisy Hopkins, age 17, was arrested 2 December 1891was sent to the Spinning House for 14 days and charged with walking with an undergraduate. This sparked a furore and a well publicised legal case.

Daisy Hopkins Cambridge Daily News 3.12.1891

For numerous other newspaper reports on the Daisy Hopkins case see Gold Street.

1899 (CDN 19.4.1899) The days of the Cambridge Spinning House are numbered. It is to be pulled down in order that a house of detention after the best approved modern ideas may arise on its site. There is no more stirring chapter in the history of modern Cambridge than that which this forbidding looking building in St Andrew’s Street recalls. It is an ugly monument of an ugly feud between the authorities of the University and town.

1901

1911

1913

Police Station and Mortuary, Charles E Holland chief constable

Fire Brigade Station

http://cambridgehistorian.blogspot.com/2013/11/early-fire-services-in-cambridge.html

1962

City of Cambridge Police

City Road Safety Office

1970

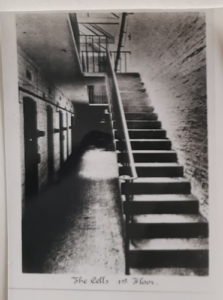

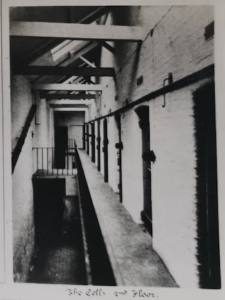

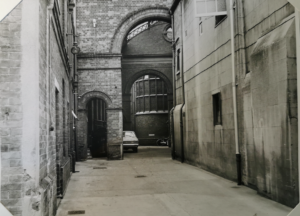

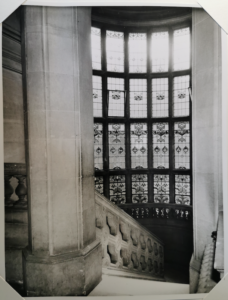

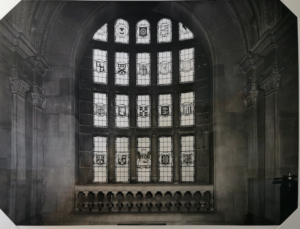

Photos (MoC) taken in June 1970 by D.C.549 Taylor of the Old Police Station:

2021 Mike Petty’s fictional picture of the Spinning House in 1838:

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.