Search by topic

- archaeology

- Building of Local Interest

- chapel

- charity

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- Listed building

- Mapping Relief

- medieval

- oral history

- poverty

- Public House

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

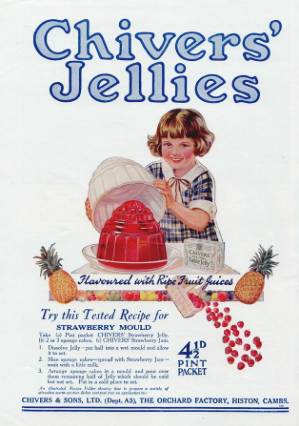

Chivers Jellies

Chivers JelliesChivers Fruit Preserving factory

History of the Fruit Preserving Factory

Chivers started making jam during a glut year in 1873.

The first jam production took place in this barn in 1873 under the supervision of a Pembroke College cook.

See: https://www.museumofcambridge.org.uk/2018/07/for-jams-and-jellies-choose-chivers/

Chivers & Sons: From Orchard to Industry — The History of Chivers in Histon

Histon came to be closely identified with one of Britain’s great preserve makers: Chivers & Sons. The story of Chivers is one of innovation, orchard farming, social welfare, and industrial change. The Chivers family had been market gardeners in Cottenham, Cambridgeshire, since the 17th century. John Chivers later moved to Histon in the early 19th century with his brother and sister. John’s sons—Philip, Stephen, and Thomas—continued in horticulture, focusing on fruit and vegetables. Stephen Chivers (1824-1907) emerged as a key figure: in about 1850 he acquired an orchard beside the newly constructed railway line through Histon. The proximity to the railway station enabled easier transport of fruit to London and northern markets.

By the 1860s, Stephen had expanded his orchards. In 1873, after a particularly abundant harvest, his sons persuaded him to try making jam. The first boiling of jam took place in a barn (close to what is now Milton Road, Impington) using fruit from their orchards.

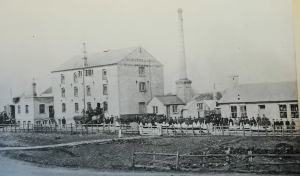

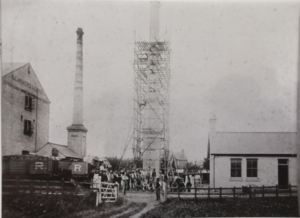

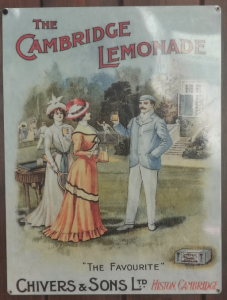

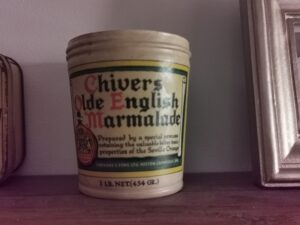

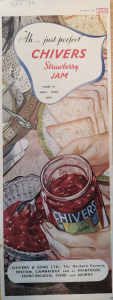

The success of those early jams led rapidly to enlargement. Around 1875, the Chivers built the Victoria Works, a dedicated factory, on land beside Histon railway station. This enabled them to scale up production and develop new products. Initially, preserves were packed in stone jars (2, 4, or 6 lbs). By about 1885 glass jars were introduced. Additional product lines followed: marmalade, dessert jellies (from 1889), custard powder, lemonade, mincemeat, later even canned fruit. The diversity reduced Chivers’ dependence on the seasonal nature of fruit growing, allowing more year-round operations and stable employment.

The factory itself was more than just jam equipment. It was a self-contained industrial estate: sawmills, blacksmiths, coopers, basket makers, paint shops, carpenters, builders, even its own water supply and electricity generation. This vertical integration helped control costs and quality.

The Chivers story is distinguished not just by its commercial success, but by its treatment of employees and its investment in the local community. They were paternalistic in the old sense: Chivers introduced profit-sharing in 1891; offered pension schemes; built model cottages for workers; provided a factory doctor and nurse; enjoyed good labour relations; and had relatively few industrial disputes.

The company also built amenity buildings for local people. For example, the Men’s Institute in Histon had reading rooms, a concert hall and other recreational facilities. The firm’s orchards and farm estates shaped the landscape around Histon, and many employees lived locally.

By the turn of the 20th century, Chivers & Sons was one of the world’s leading preserve makers. They had extended their orchard acreage (by 1896 about 500 acres in their own ownership in Histon and around there, plus more rented land) and by the 1930s, some sources suggest nearly 8,000 acres under their control.

They also pushed technical innovation. Their chief engineer, Charles Lack, developed sophisticated canning and jar-filling machinery, vacuum caps, fruit sorting, sterilisation methods, and more, which kept them competitive. Exports of Chivers’ products reached many parts of the British Empire and beyond. Blackcurrant purée, for example, became especially important in the WWII era (in part due to its vitamin C content).

After WWII, Chivers began to lose its dominant position. Modernisation lagged, competition increased, markets shifted, and consumer tastes changed. In 1959 the farms and factories were sold to Schweppes. Nevertheless, the Chivers family repurchased most of the farms in 1961.

Later, the preserve business in Histon was merged into wider brands. Chivers was joined with Hartley’s under Schweppes as Hartley-Chivers. Eventually Chivers’ own name was phased out in the UK market in many contexts; many products were rebranded under Hartley’s.

Today the Chivers name still survives (especially in exports and under other ownership, such as by Boyne Valley in Ireland), and Histon’s factory continues in various forms as part of preserve and food manufacturing under newer corporate ownership.

Chivers & Sons played several interlocking roles in Histon and Impington: it transformed what had been primarily agricultural land into a mixed industrial and farming economy; it provided stable employment and improved welfare in a rural area—income, housing, social amenities; and it influenced the layout, housing development, and growth of the local population. The presence of the factory stimulated further settlement. (AI 2025)

This four storey factory was erected in 1875.

Parchment covers were tied onto the jam jars and then hand labelled.

Gerald Dawbarn was the leading salesman. He would sit in his hansom cab and expect buyers to come out of their shops to hand him their orders.

The steam lorry was bought from Elvedon, Norfolk, in 1902. it had a Thorneycroft engine using paraffin as fuel. It was used at Histon for three years.

1914

At the outbreak of war, Chivers employed 314 men and 150 women. The Government very quickly placed a contract for tinned food. By the ned of the year three million pounds of jams and marmalades had been despatched to the forces. Dried vegetables were also produced. By the end of the war the company was employing 2,000 workers, two thirds of them women. Of 541 employees who served in the armed forces, 30 did not return.

Many of Chivers workers joined the Royal Engineers. Charles Ison, wheelwright and joiner ended up making wheels for the army.

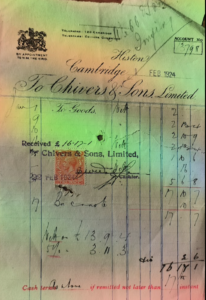

1924

See: http://letslookagain.com/tag/history-of-chivers/

Projects

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

Licence

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0