Search by topic

- archaeology

- Building of Local Interest

- charity

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- Listed building

- Mapping Relief

- medieval

- oral history

- poverty

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

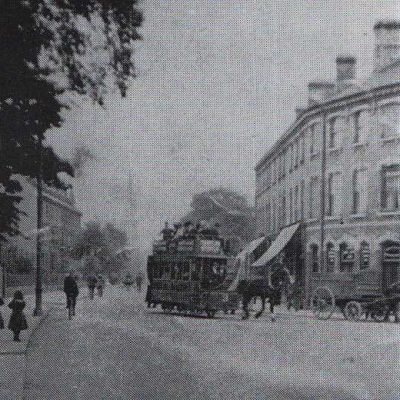

Wilton Terrace Station Road

Wilton Terrace Station RoadWilton Terrace, Station Road (demolished 2016)

History of Wilton Terrace

Wilton Terrace, Station Road

WILTON TERRACE, 32-38 STATION ROAD

Terrace of 4, 2-bay houses built sometime between 1863-1888. Gault brick with red brick detailing. Crow-stepped end gables. The panelled entrance doors are in bays 1,4,5 and 8 and have steps up. Above are 2/2 sashes with stone lintels and red brick relieving arches to ground and first floors. In the other bays are two storey bay windows with slate roofs. The front window of each bay has 2/2 sashes, the narrow side windows are plate glass sashes. Glazed brick ‘spandrel’ panels above and below the ground floor windows. Corbelled brick eaves detailing. Large central chimney stacks in each pair of houses. No fines concrete boundary wall to front, high gault brick boundary wall to rear; both of interest.

Similar materials and detailing as 9-29. Not of sufficient quality to list but worthy of BLI status. The front wall and landscaped former carriage-drive and rear wall are good surviving features.

(Cambridge City Council Station Area Conservation Appraisal)

The information below is drawn from the document ‘Wilton Terrace Station Road Cambridge – The Case for Listing’ researched by the Friends of Wilton Terrace.

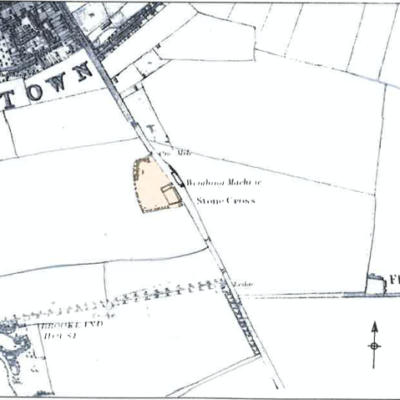

Wilton Terrace was built in 1885 – four four-storey houses with semi-basements unusually built of insitu-caste concrete. No. 38 was slightly wider than the others and had a side door.

On 15/11/1883 Arthur John Gray had his plans for four houses in Station Road approved. In the 1871 census Gray was recorded as employing 40 men. Gray had worked with the local architect Richard Reynolds Rowe as early as 1858 (when they were awarded the contract for Barnwell Abbey School) and Gray was responsible for most of the significant buildings in the station area. Gray retired to the Isle of Wight and died in 1895. The value of his estate at probate was £28,398.18.11 and the first property mentioned in his will is Wilton Terrace. It was first left to his wife, and then, after her death, to Walter Gardiner, Bursar of Clare College. Charles Bidwell, the surveyor who valued the estate in 1896, described the houses as each having a kitchen, scullery, pantry, coal house and W.C. in the basement, an entrance hall, dining room and drawing room on the ground floor, three bedrooms, bathroom and W.C. on the first floor and three servants’ rooms on the second floor. The gross rents were £203 5s 0d and the estimated value £3,584.

The status of the buildings was underlined by features such as the decoration of encaustic tiles, bay windows at the rear, dual access for carriages in and out of the property as well as the location so near to the station.

The terrace was named after Joseph Wilton (1722-1803), the most distinguished sculptor of his generation.

The presence of Alfred Kett at no. 1 Wilton Terrace, and Thomas Ball at no.3, gives an insight into the genesis of Wilton Terrace. In developing Wilton Terrace, Gray was almost certainly responding to a growing demand from an emerging and entrepreneurial middle class for housing that reflected its new elevated status. Less opulent than the grand villas of the established wealthy on the north-east side of Station Road, it was nevertheless housing on a grander scale than the small terraced streets elsewhere.

There are a number of design features that confirms the elevated status of Wilton Terrace. For example, no other terrace of the same period in Cambridge boasts a carriageway for the access and egress of coaches. Lime trees (pollarded in their day), a fashionable status symbol of the time, line the frontage. With service accommodation in the basement, live-in servants’ rooms on the top floor, and two intermediate floors for the master and his family, the houses are grand indeed for a terraced house. Unusual too, are the bay windows on the rear of the property. Remarkably, all these features remain substantially intact and collectively rare. Furthermore, the patterned gable ends of the terrace match exactly, demonstrating the building is complete as originally conceived. Another reminder of the elevated status of Wilton Terrace is the external decoration – it is unusually profuse and sophisticated for terraced housing.

Overall the brickwork is a warm cream colour characteristic of a local brick made from gault clay quarried from pits on the Newmarket Road. Hard red bricks, not red rubbers, are used to provide patterning in a contrasting colour on the front elevation and the gable walls. All four corners of the building have red brick quoins which interrupt the red brick string courses that wrap around the gable walls from the front elevation. Clearly there was an expectation the building would be seen in three dimensions as a stand-alone structure – that is, not just presenting a street frontage like most terraced housing in Cambridge. The quality of the bricks and brickwork is generally good and the colour consistent.

Where stone might otherwise have been expected, the bay windows, lintels, front and rear external steps (supported on arched soffits), the external basement walls (appearing to act as a plinth on which the super structure is built), the soft-water storage tanks beneath the rear access basement steps, and the front boundary wall and pillars are all constructed of concrete employing Portland cement; this is extremely unusual and innovative for the time. Some elements such as the lintels may have been precast. As a consequence, Wilton Terrace may be an early example of Portland cement used in this way. It is possible the reason for the change to Portland cement from the more commonly used Parkers Roman or Sheppey Cement

(patented in 1796) may be as a consequence of an earlier ruling by the Royal Navy (fearful for the stability of the cliffs and their collapse onto the Harwich naval base below) banning the quarrying of Septaria clay nodules – an essential ingredient of Parkers Roman Cement. This is potentially fascinating and needs confirming via further research.

It seems likely that the architect was Richard Reynolds Rowe or closely associated with him. Research has shown that documentary evidence of Richard Reynolds Rowe’s considerable portfolio of work is sparse. Accordingly, it is not surprising tangible evidence has yet to emerge linking him firmly to Wilton Terrace. But such is the terrace’s architectural merit, linking it to Rowe may be of peripheral importance only; its worth speaks for itself. Nevertheless, the search continues because, given all the other indicators, proof seems tantalisingly close.

The style and ingenuity of the detailing would suggest Rowe was either involved first hand or exercised considerable influence over those who were its designers. For example, the palette

and balance of materials and colours bears comparison with his Grade II Listed Corn Exchange in the centre of Cambridge. And the inventiveness in the use of well-established architectural

details resonates with so much of his other residential work across Victorian Cambridge.

His association with Rattee and Kett for the Colleges, (particularly Jesus College where he was its retained architect), together with his connections with the developer Gray, makes it almost

inconceivable that Rowe did not have a hand in the design of Wilton Terrace. And the land on which it stands belonged to Jesus!

The terrace was demolished at the end of 2016 as part of the CB1 development.

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0