Search by topic

- archaeology

- architecture

- bricklayer

- Building of Local Interest

- carpenter

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- listed building

- medieval

- oral history

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

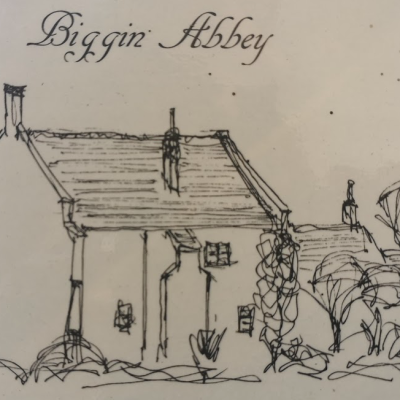

1 & 3 High Street, Tudor House, Kings Head Public House, Hauxton

Listed building:

C15 with C16 and C20 alterations. Timber frame, rendered with steeply pitched tiled gable roofs and a yellow brick ridge stack. Plan of hall and crosswing. Hall, C15 of one storey and attic. One dormer and two windows and a doorway, all C20. The doorway is possibly on the site of the original entry to the medieval cross-passage.

Brenda Purkiss has written about the village and its history including Tudor House:

Village Environment

Despite significant housing development in the 1980s, Hauxton village, with a population of around 700 today no longer supports a pub, general grocery store or post-office. The ancient 11th-century church still holds services and there is a village hall, primary school, allotments and private gym. Commercially, in addition to arable and livestock farming, there are a few small-scale enterprises: physiotherapy practice, agricultural machinery, private fishing and game reserve, organic shop and asparagus grower. The village enjoys a small but strong sense of community reflected in the activity of the PCC, play-group, environmental protest group and Women’s Institute.

In the past, the village was more vibrant. Founded during World War I, an agro-chemical business flourished until 2006 – it began with the excavation of coprolite (fossilised dinosaur droppings) used in fertilizer manufacture. Also providing employment were a dairy, pantile works, gravel pit, disability vehicle business, fuel station, post office, village store and three pubs – harvesting of frogs from the water meadows for scientific research was a more unusual village occupation! In the 19thcentury, a prosperous extension to the village was located on the main road where it crosses the river Cam. It included a mill that had probably existed on this site since Roman times. Its heyday was the late 18th century when oil seed was crushed and corn, coal, pitch, tar, brick and timber for building were traded; close by, two ale houses (the Ship and Chequers) served passenger coaches travelling between Cambridge and London. Going further back, evidence of continuous settlement dates to the Bronze age; when Tudor House was built, there were around 20 households in the village and an average of five baptisms per year were recorded (British History On-line and parish register).

The Building and Village Social History

It is not possible to determine who built Tudor House from surviving records. Its solid construction and prominent position suggest that the builder may have been a person of some significance. He was unlikely to have been an ‘hospitmanus’, 15th-century Innkeeper, as ale-houses at this time were often cited, for example in judicial reports, as places frequented by disreputable trouble-makers (Brown 2011). Also difficult to determine is when Tudor House first became an ‘ale-house’. The earliest documentary evidence is provided on an 1836 map based on an 1806 survey; in 1852, an inquest is recorded as having been held in the ‘King’s Head’. Village anecdotes, recorded in a local publication ‘In Times Past’ (Elliot & Jordan 1993,) suggest that the ‘king’ was Charles I who may have taken shelter in a barn behind the house in the 17th century; folklore also suggests that Cromwell may have stabled his horse on the site. Evidence to support these tales is elusive, both protagonists visited the area many times and, as shown in the 1799 Enclosure Map, there were several outbuildings in this period.

Figure 1: 1799 Enclosure Map – Tudor House is 35a, allocated to one ‘Swan Wallis’

Early in the 20th-century, during annual visits of the fair, the owner of a dancing bear would enjoy a beer in the Tap Room whilst keeping an eye on his chained beast on the village green opposite. In 1926, the publican’s wife was a founder of the village Women’s Institute which met monthly in the Club Room; meetings sometimes took the form of recitals and concerts (including performances from the band led by a publican’s daughter) and were attended by folk from surrounding villages. For a period in the pre TV-dominated 1930s and 40s, film nights were run by ‘Globe Cinema Services’; amateur theatricals, folk dances, dominios and whist drives were also regular village favourites (Elliot & Jordan, 1993).

Photograph 2 – 20th-CenturyTap Room Dominos and Club Room Fancy Dress

During World War II, the civil service used the Club Room to issue ration cards and gas masks. It was also a distribution centre for the additional food rations (meat pies) issued only to harvest labourers. In the 1950’s, an unusual regular was a young bull from the nearby dairy farm who enjoyed a Sunday half-pint of Guiness (local residents; WI, Elliot and Jordan).

Photograph 3 – Sunday Morning Regular

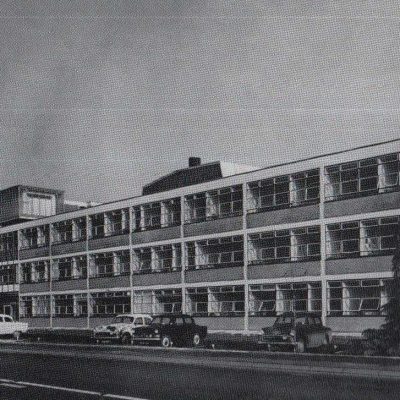

The pub ceased trading in 1958 when the owner, Phillips brewery, sold-up; income had dwindled due to the popularity of television and competition from supermarkets and the newly-built sports and social club on the nearby ‘Pest-control’ factory complex. Interestingly, the 1958 planning application, Appendix 4, indicates that a day-nursery had been proposed for the Club House; not surprisingly in this pre-feminist, working mother era, it was not pursued.

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0