Search by topic

- archaeology

- architecture

- bricklayer

- Building of Local Interest

- carpenter

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- listed building

- medieval

- oral history

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

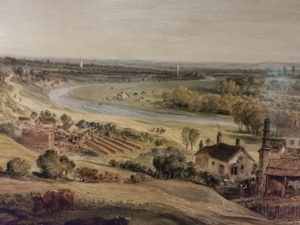

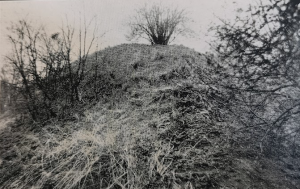

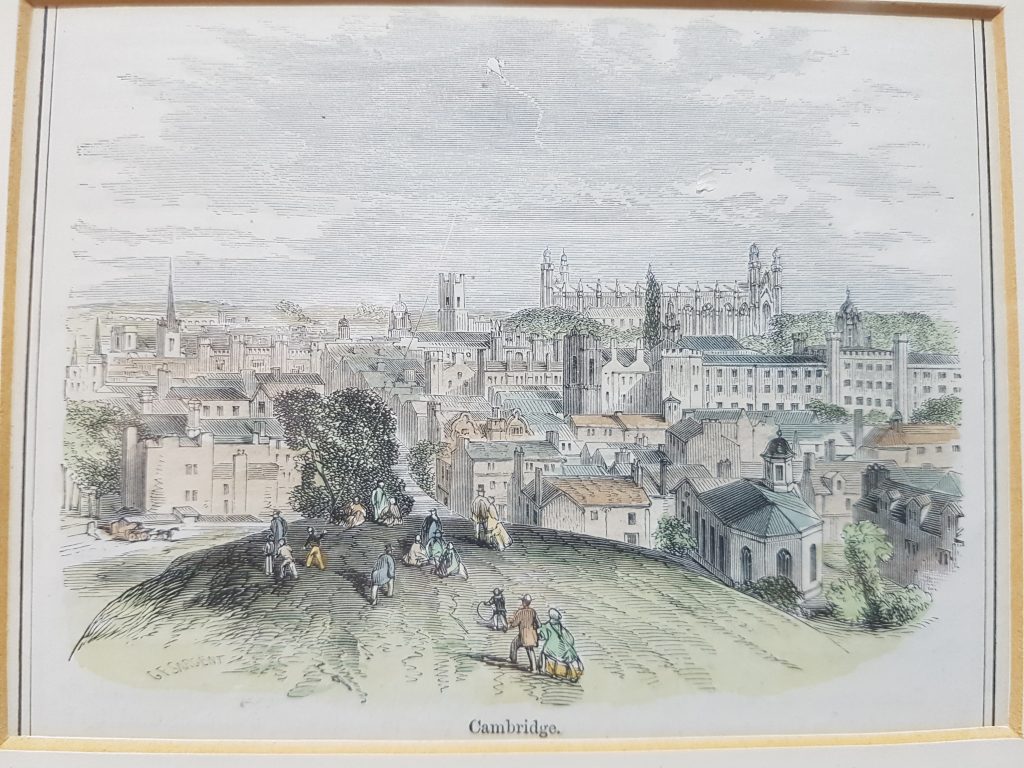

Cambridge from castle Mount - G F Sargent mid 19th century

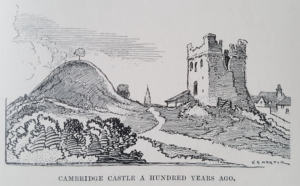

Cambridge from castle Mount - G F Sargent mid 19th centuryCambridge Castle, County Gaol

History of Cambridge Castle

Caroline Biggs interviewed local historian Allan Brigham in 2013 from the top of Castle Mound.

The Roman town was known in the Antonine Itineraries as Duroliponte (CAS Vol 1999 Roman Cambridge). It had already been an extensive Iron Age settlement with strong links to the Catuvellaunian and Trinovantian kingdoms to the south, lying across key routes. After the Roman Conquest a series of enclosures were built to protect the crossroads and the river crossing. By AD70 a fort had been built and the road, known later as Akeman Street, ran through it. Another road, known later as the Via Devana, also ran into the site across the river.

Early in the 2nd century further streets were built parallel to Akeman Street. A stone mansio with hypocaust from this time indicates that Cambridge was part of the Hadrianic development of the cursus publicus from Ermine Street to the Fens. There dates from this time a massive subterranean ceremonial site or shrine. There is evidence of burials involving luxury goods and sacrifices of dogs and horses.

By the 4th century there were new buildings and a general reorganisation of the site with new defences. The walled settlement may have lasted into the 5th century and there is no sign of deliberate destruction.

In chapter 7 of CAS 1999 ‘Roman Cambridge’, Alison Taylor draws attention to the debate on what exactly constituted a small town in Roman Britain. She notes that evidence for the shape of the fort is not conclusive; there is little evidence of military equipment. However, after the rebellion of AD60 a fort at Cambridge could have been a useful point from which to monitor dissidents.

She concludes that there is still relatively little evidence of ordinary commercial life even though areas such as Horningsea, Milton and Waterbeach had huge areas used in pottery production. There is little evidence of shops fronting onto streets. In essence Cambridge seems to have been an existing Iron Age settlement that was developed under Emperor Hadrian as an administrative centre for the local region.

In 1923 Cyril Fox wrote: In the Borough of Cambridge is a four-sided enclosure of some 28 acres the limits of which can fairly accurately be determined and which is almost certainly a Roman fortified town. Two important Roman roads … crossed here, and numerous finds are recorded within the area. … Coin finds range from Nero to Honorius…. Bowtell records the destruction of what was apparently a portion of the Roman wall and gate near Castle Street in 1804.

The Saxon settlement was originally within the ramparts of the Roman fort. It is known that there was some destruction during the conflicts between the kingdoms of Mercia and East Anglia. In 634AD the Mercian king Penda conquered the East Anglians at the site. The Venerable Bede mentions the site when he describes the monks from Ely coming in 695 in search of a suitable coffin for the founder of their monastery, St Etheldreda. They are said to have found a coffin at the foot of Castle Hill in ‘a waste chester called Grantacaester’ i.e. the Roman camp next to the Granta, the old name for the River Cam. (Peter Bryan, ‘Cambridge – The Shaping of the City’ 2008, p.12)

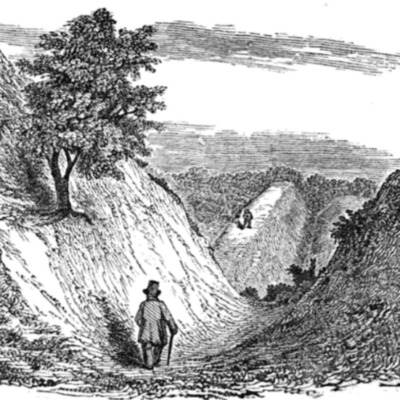

The motte is all that remains of the castle built by William the Conqueror in 1068 to control the river crossing. It lay within the stone walls of the Roman town. In the process 27 houses were demolished. A stone bailey was rebuilt in stone by Edward in 1294. It seems to have been surrounded by wet moats.

CAS 2005 contains the article Cambridge Castle Hill: Excavations of Saxon, medieval and Post-Medieval deposits, Saxon execution site and a Medieval coinhoard by Craig Cessford and Alison Dickens. In this article it states that in 866 Cambridge became part of the Danelaw. This lasted until 917 when the region submitted to Edward of Wessex and a settlement followed in920.

See Defending Cambridge, Mike Osborne, (2013) for a detailed description of the Norman castle.

The Norman Castle was the office of the sheriff, with dungeons where he could keep prisoners and where the monthly county court was held. being made of wood, maintenance was cheap and in the century ending 1234 less than 30s a year was spent on repairs. The garrison was small and when it surrendered to the Barons in SKing John’s reign it contained only 20 men.

The castle was not a strong one, even as a prison. Around the year 1260 a woman named Constance was arrested for murder by the constables of Fulbourn. She was brought to Cambridge Castle where Sir William le Moyne was holding a county court. Sir William declined to lock her up but the constables of Fulbourn tried to insist. During this argument Constance escaped and both sheriff and constables were fined. A little later five prisoners escaped and took sanctuary in All Saints’ church.

A document in the Public Record Office dated 1236 lists twelve landowners in Cambridgeshire who were charged with payments for the upkeep of the castle. Six of these had to pay 6s 8d, a mark.Then, in the reign of Edward I, the castle was rebuilt form c. 1283. In Michaelmas 1286 the Sheriff claimed to have spent £408 on the hall, gate and walls. In 1297 £407 was spent on a new gate, the next year £161 on thatching; in 1299 a new kitchen and bakehouse were built. There were sometimes over 100 men at work on the castle per week.

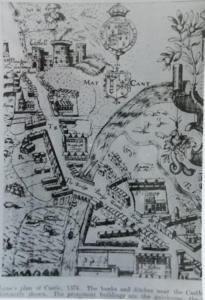

The first area to be rebuilt by Edward I was the Great Hall. Up to Midsummer 1286, over £100 was spent on the hall. The Curtain Wall was finished in 1287. The Great Gate was built at the same time; this survived until 1840 and took two years to build. In 1288 the roof was covered in lead. (for other details of the rebuilding see W M Palmer, Cambridge Castle, 1928.)

The site of the Barbican. The ‘Three Tuns’ was outside it, but the next house, formerly the ‘White Swan’ is on it. (Palmer 1928)

Edward I stayed at the castle 24-25th March, 1293. He was the first king to stay on the site. He didn’t like the smell of the stable under the hall so that was rebuilt. The garrison was enlarged to 30 men in 1317.

There are numerous records of escapes form the prison, usually in groups.

1346 Four thieves broke their chains and killed a gaoler with a pole-axe, taking sanctuary in the church f All Saints.

1349 A prisoner snatched a knife from a gaoler, stabbed him; four men and one woman escaped to sanctuary.

1359 Sir John de Moleyns were confined with his wife Gilliam for four months. He died and the coroner recorded that he was a great conspirator and died a natural death at the age of 70.

1368 workmen at the castle borrowed a ladder to put two new gargoyles and a leaden spout on the roof of the Great Gate, so they borrowed a long ladder from the Friars Minor (Sidney College later) giving the Friar who bought it 4d. He was given 3d to take it back.

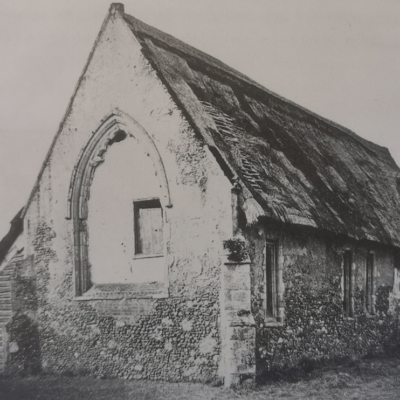

By 1367 the castle was already in a defective state although even in 1585 attempts were made to retain the curtain wall. By 1606 the S.W. gatehouse was the only complete building left because of its use as a prison.

1418 new stocks were made in the castle yard at the cost of £2 3s 4d (Foreign Roll 9, Henry F)

1439 £3 17s 2d for repairs to wall (Sheriff’s acct., 12/21)

1441 The Great Hall and chamber were without a roof in 1441 and the king used the stones of these buildings for his new College.

1449 the sheriff, William Alyngton, spent £40 on repairs to the gatehouse (Foreign acct. 28, Henry VI.)

1475 Thomas May, yeoman, porter of Cambridge Castle, made a complaint to the Lord Chancellor that Roger atte gate, sergeant-at-arms, constable of the castle, would not suffer him to occupy and use the herbage of the castle ditches

1528 Philip Paris spent £5 on repairing the castle wall and gaol. (Sheriff’s Accounts, Roll 13)

1580 appointment of Ralph Killingbeck as gaoler. At this time there were six prisoners, two of them debtors belonging to the upper classes. Robert Wray had a debt of £600. the other debtor was Thomas Brakin, lord of the manor of Chesterton. He owed around £1,000. the following year he sold the manor to John Styward, father of lady Jermy.

1585 curtain wall repaired but other buildings pulled down. Emmanuel College bought salvaged stone.

1592 identure dated 7th December: Sir Henry Cromwell, sheriff, appoints William Silvertop, yeoman, to be gaoler of Cambridge castle. the document goes on to list the prisoners: Thomas Gosson and Susan Arthur, condemned and reprieved; William Fawys, John Peepes, Thomas Holmes, Thomas Stukley, for suspicion of felony; William Kisby, John Thow and Mary Bell, for vagrancy; John White (sent in by Thomas Burge, doctor of law, and Ralph Tyrer B.D. delegate judges appointed by the University of Cambridge, for a matter of inquiry between Dr Newcombe and John White until he has satisfied £100 to Dr Newcombe; Thomas Sterne and Daniel Ventrys, outlawed; John Noble for debt of £8 and 16s 8d fees.

1598 the sheriff, Oliver Cromwell, appointed George Robson and his wife gaolers on December 9th. There were 20 prisoners of whom 3 were debtors. One was a recusant, Nicholas Bestwyk, who was later suspected of being concerned in the gunpowder plot. However, George Robson himself became a prisoner at the suit of St John Peyton. Robson’s appointment as gaoler therefor only lasted nine days for on December 18th William Piper was appointed gaoler and Robson no longer appears in the list of prisoners.

1606 only gate house remained and a small piece of curtain wall on which Jury House was built. The castle was surveyed by John Cowell, master of Trinity Hall.

In 1643, because of Cambridge being the headquarters of the Eastern Counties Association, the Bailey works were reconstructed as a bastioned trace fort. In 1647 the new defences were slighted but three bastions remained.

For more information about Cambridge and the Civil War fortifications see: Mike Osborne, Defending Cambridgeshire.

During the reign of Charles I there was a long law suit between a London speculator and the Lord of the Manor of Chesterton concerning the rights to the waste lands about the castle, and in particular the ownership of five small cottages which had been built on ground made by digging down the castle bank into the ditch next to Castle Street. (See Palmer, Cambridge Castle)

This court case and the witness statements provides a great deal of information about the castle in the 16th and 17th centuries. A large number of witnesses were brought by Lady Joan Jermy, owner of Chesterton manor, to prove that the castle was in the manor of Chesterton, even though the town of Cambridge lay on three sides of the castle.

John Gibson of Cottenham, wheelwright, aged 63, said that he knew Goode’s cottage stood on the waste of Chesterton manor because he was apprenticed in that house and went to Chesterton parish church. He said prisoners who died or were excecuted were buried at Chesterton.

John Theaker of Chesterton, shepherd, aged 79, had known the castle since 1558 and had gone with the procession from Chesterton when they beat the boundaries taking in the castle and Goode’s and Stanton’s cottages.

Some of the ages of the witnesses are remarkable. Ursula, wife of Robert Simpkin of Cambridge gave her age as 102. William Clapham of Girton, 80; John Raby of Landbeach, 84; William Moulton of Histon, 92.

The actual situation was that although the castle was in the parish opf Chesterton, it was the private property of the king.

The legal case shows that there was a moat with water around the castle until the end of the 16th century.

1643 castle defences were remodelled by Parliamentary forces.

1646 after most soldiers had marched to Newark, garrison consisted of two sergeants and 25 foot soldiers.

1660 Thomas Sadd, keeper of the castle

1664/5 March Assizes at Castle

(7/3) Execution of man believed to be Edward Sterne alias Perrey for robbery of Mr Morden. Defendant refused to plea so he was pressed to death. (Samuel Newton diary).

(11/3) Roger Nelson of Foxton hanged for the murder of his wife.

1688

10th June (Samuel Newton diary):

It is this day further confirmed that the Queens Majestie was yesterday the 10th June 1688 being Sunday delivered of the Prince of Wales about 10 of the clock in the forenoone, this Munday night upon that occasion Great St Maryes Bells rang and a Bonfire was on the Great Hill in Cambridge and the souldiers there mett and gave severall volleys of shott.

1718

Simon Ockley, Professor of Arabic, was imprisoned for debt. From the April of 1718 he began to hear constant noises, both day and night. Others witnessed the same noises which included vibrations which nearly threw them off their chairs. He was released in July and went home to Swavesey but continued to be tormented by ‘phantoms’. He died in 1720, a ‘frightened and haunted man’. (see H O Evennett ‘An ancient Cambridge poltergeist‘ British Journal of Psychical Research 2 (1929) pp172-179. (The Cambridge Ghost Book, 2000, Halliday and Murdie).

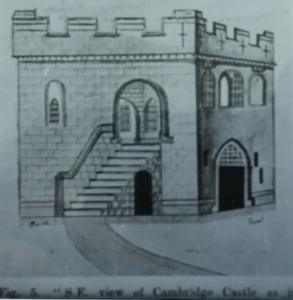

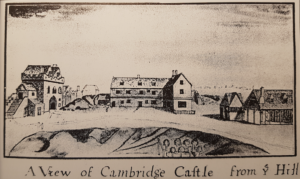

Cambridge Castle by James Essex 1740. L to R: medieval gatehouse, Cromwellian barracks, Elizabethan law courts (Shire Hall)

1730

1759 account from Cambridge Chronicle where prisoners in the lower gaol filed off their irons, broke 14 locks and a massive iron bar. They were heard by debtors in the upper prison who alerted the gaoler and they were recaptured.

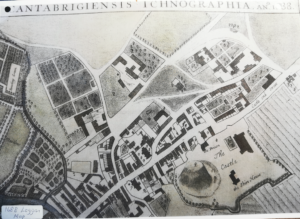

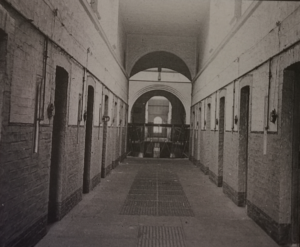

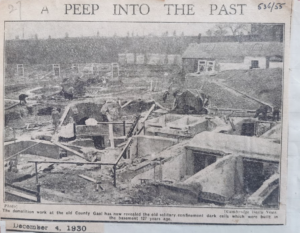

Between 1802 and 1847 a new octagonal County gaol designed by G Byfield was built. In 1842 the SW gatehouse was pulled down to make way for the Court House, itself demolished in 1954. In 1932 the new Shire Hall was built on the site freed by the demolition of the County gaol.

See Enid Porter’s article: Crime and Punishment

Documents about the castle’s role as a prison can be found here:

There is a Wikipedia entry.

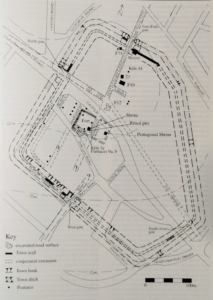

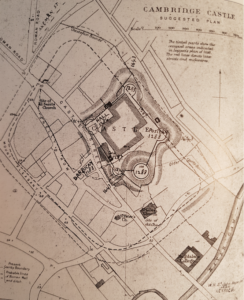

The following map from 1895 shows the probable line of the Roman wall and ditch. Peter Bryan’s map in ‘Cambridge – The Shaping of the City’ 2008 places the Roman Military Fort within the area formed by Castle Road at the SE, Castle Street at the NE and Shelley Row at the SW.

1780 17th March

Elizabeth Butchell hung for concealing the birth of a child

1786 5th August

George Miller hung for the murder of Elizabeth Hunt. His body was given for dissection.

1782 – 1804

William Gregory was keeper of the gaol. He married Rachel Phipps. According to family history, this William Gregory III was baptised at St Giles, Cambridge in 1728, grandson of William Gregory I (died 1713), an innkeeper, and son of William Gregory II (1695-1771) and his wife Elizabeth. The family appear to have had a long connection with St Bene’t’s church parish where they were baptised and buried. William III was married in 1760 at Holy Trinity, Ely to Rachel Phipps of Mepal. Up until 1781 he held parish office at St Bene’t including Overseer of the Poor. in 1782 he was appointed Keeper of the Gaol and Bridewell at the Castle where there were 15 debtors and 3 felons. His salary was £90 per year but he also had to pay for a turnkey – £18.in 1782, John Howard, the prison reformer, commended the Keeper as attentive and humane. in 1796 William was fined £20 for allowing Edward Scott to escape as he crossed the yard for divine service, the yard being insecure.Scott was recaptured and the fine rescinded. In 1802 there were 6 debtors and 1 felon in the gaol, and 7 men and 2 women in the Bridewell. Food consisted of bread with potatoes and stewed vegetables, and on Sunday a strong soup made of ox-cheek or beef. While he was Gaoler there were 19 executions by hired hangmen, for crimes such as forging bank notes, rape, highway robbery, murder sheep theft and stealing silver plate from an Alderman. He died in 1804 having been Keeper of the Gaol for 22 years.

1801 March 28th

William Grimshaw (a chimney sweep) hung for housebreaking

1802 April 3rd

William Wright and John Bullock hung for arson

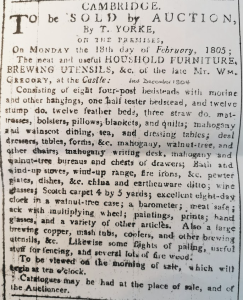

1805

William Gregory died December 1804.

1812

March 28th: William Nightingale alias Bird hung for forgery. In 1999 Mike Petty wrote that Nightingale was a 29 year old whose business as a carpenter in London had failed. He started forging bank notes. He’d gone to the Black Lion in Silver Street and paid for dinner with a £5 note. Mortlock’s Bank said it was a forgery and Nightingale was arrrested in Godmanchester.

August 8th: Daniel Dawson hung for crime of poisoning a horse at Newmarket. The Cambridge Chronicle 23.8.1811 explains that Daniel was originally a groom and one of the best judges of the capabilities of race horses. He was charged with poisoning two horses at the Newmarket Spring Meeting in 1809. The poison was alleged to have been prepared for Mr Willson’s Wizard, the winner of the 2000 guineas stake, but which fell to the lot of two others.

1819 6th August

Execution of Thomas Weems for murder of his wife.

1824 3rd April

John Lane executed for crime of rape committed in the parish of Cheveley.

1829 April 11

William Osborne was hung for murder

1830 April 3rd

Execution of David Howard, William Reader and William Turner for arson. This is reported in the Morning Advertiser 7th April 1830. Turner (of Bartlow) and Reader had set fire to the farm yard of Mr Chalk of Linton, and Howard to a farm in Badlingham.

1833

March 30th: Execution by hanging of William Westnott and Charles Carter for attempted murder of a gamekeeper. The Execution is described in the Cambridgeshire Chronicle and Journal 5th April 1833 but details of the trial and events of the attempted murder are harder to find on line.

December 7th: Execution by hanging of John Stallon, the Great Shelford incendiary (arsonist)

John Stallan – Shelford Arsonist – 1833

1850 13th April

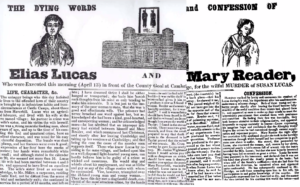

Elias Lucas and Mary Reeder of Castle Camps were hanged for the murder of Mary’s sister, Susan Lucas. Susan was married to Elias and it was alleged that Mary, while living with the couple, had committed adultery with Elias and then killed her sister with arsenic. It was a public execution; Josiah Chater did not attend but recorded in his diary:

I went up at 9 o’clock this morning to see the gallows prepared for the two poor souls condemned to die at 12. They were hung at that time and thousands of people were there to witness the sight. The town has been full all day and hundreds have been rolling about Market Street drunk, proving what a demoralizing effect public executions have upon the people.

The case is described in John Bell’s Cambridgeshire Crimes.

Cambridge Independent Press 20/4/1850:

EXECUTION OF ELIAS LUCAS & MARY REEDER.

The following appeared in our third edition of last week:

On Saturday laat, at twwlve o’clock, Elias Lucas aged 24, and Mary Reeder, aged 19, died upon the public scaffold, in front of our County Gaol. There is no one possessed of the commonest feelings of humanity but must fuel a pang upon the reflection that two persons so young in year, in the very bloom of youth, should have rushed into a crime that has called down upon them the very heaviest penalty the law of man can inflict. But, with all our sorrow for the criminals, with all our horror at their unhallowed fate, we must not forget the crime, which has brought them to so ignominious a death. We shuddered at the dreadful murder of the venerable nobleman, Lord William Russell at the hands of the midnight assassin; we abhorred the miscreant Rush, who by a deep-laid plan to gain pecuniary object, sent to their last account Mr. Jermy and his son ; the murder of O’Connor by the Mannings, is yet fresh in the memory of the public; husband and wife conspired to sacrifice the life of a man whom they called their friend, that they might rob him of his wealth, and fly to a distant land to escape justice here, and revel in their ill-gotten wealth; all these great criminals have gained an odious immortality: but in what respect were their fearful deeds more dreadful than that perpetrated at the village of fCastle Camps, by Elias Lucasc and Mary Reeder? Six years ago, Elias Lucas married an attractive and modest village maiden, named Susan Reeder; her friends, though in humble life, were respectable and respected; Lucas and his wife lived happily together, until his friends, thoughtless of the consequences, cruelly sought to prejudice his mind against her; Elias was blythe at his work, frank and social among his companions, and apparently a good-natured man. Susan Lucas had sister Mary, younger than herself, to whom she had evinced the tenderest affection; this girl, fair to look upon and with countenance that should have told of a heart free from guile became ill, at least she complained of a pain in the chest; and Susan, knowing that she had no mother, felt that, if nursing and sisterly attention could conduce to her health, hers was the home for Mary. How was this tenderness requited? A liaison sprang up between Susan Lucas’s husband and the sister she had brought home to cherish and these two criminals, that they might enjoy their illicit intercourse without molestation, entered in to a compact to destroy the life of one to whom both were bound by the strongest ties of nature – she was the wife the one; the sister of the other. Crime is ever frightful to contemplate but when a deed so black in character, so fatal in its effects, is committed in an agricultural village, where simplicity of life and innocence of manners should be its characteristics, it has a more thrilling effect.

These criminals determined to murder Susan Lucas, far the only reason that she was in their way. An indiscreet master had entrusted Lucas with some arsenic, for the purpose of destroying it; a poison more dreadful in its effects, and inflicting more physical suffering than any other ; instead of doing the bidding of his master, Lucas took it home, and placed it on a top shelf in a cupboard. A portion of this poison was taken to destroy their unsuspecting victim; not by the man; for with a cunning, which he thought would free him from the consequences of the crime if detection followed, he gave directions how, when, what quantity, and where it was to be administered. The fatal night came, and Mary fetched the poison from its hiding place, and unseen by her sister, thrust it beneath some bread crumbed for Susan’s supper. Poor, sacrificed woman! in the presence of her murderers — before the sight of those who should have her as they loved themselves — she ate the fatal mess. She complained of its taste, and her recreant husband, with a brutal attempt at wit, said ” I would eat it if killed me.” For twenty-four hours did that poor woman endure the most horrid torture – she rolled out of bed in agony; she purged and vomitted the live-long night and part of the next day. What were her murderers doing this time? Seeping, one, at any rate, by her side; where Elias was we cannot say, as it does not transpire; but, said Mary Reeder. “he slept like a top.” Death at length terminated the poor creature’s sufferings; but she never breathed a suspicion of foul play; and let us hope that, amidst all her agony, the fatal truth never flashed across her unsuspecting nature. Fact after fact, link by link of evidence was the crime of murder brought home to husband and sister. At his trial, he showed disgusting levity; and she an astonishing apathy. Since their condemnation, they evinced the usual prison penitence; for though we should be sorry to say one illiberal word of the murderers, we question if that penitence has not been brought about much earlier by the verdict of GUILTY than it would if Lucas had had the opportunity of standing ” the bottle of gin” he talked about, if he “got clear of the job,” and for “the pleasure of being a single man again.”

Mary Reeder, though expressing great penitence, has varied in her statements. On leaving the dock, after trial, she stoutly maintained her innocence; but this may attributed to the natural excitement she laboured under at that terrible moment on the following day, she acknowledged that she put the poison in the basin by direction of Lucas; and to this statement she adhered for a fortnight, once adding that he told her to use as much arsenic at would cover a shilling. On Sunday, the Rev. Mr. Roberts, (who has been extremely attentive to the convicts, he having, during the past fortnight, officiated for Mr. Ventris, who is ill) preached the condemned sermon, in the Gaol Chapel, the convicts and all the prisoners ia the gaol being present. The sermon was preached from Luke xv. 10., “There is joy in the presence of the angels of God over one sinner that repenteth.” The beautiful discourse which followed had evidently powerful effect upon the congregation, many being subdued to tears; and when the preacher told them that before the dawn of another Sabbath, two present would be dead and their graves, they sobbed audibly. In the evening, the convicts were suffered to have an interview, for the first time since their condemnation. They then manifested no excitement, but chatted very coolly together, she saying him — “On my oath, Lucas, and you know I speak the truth, I should never have put the poison in the basin but for your persuasion; you told me to put as much in as would cover a shilling.” On the following morning, she made a fresh statement, in which she entirely exonerated Lucas from any participation in the crime for which both were condemned to suffer. She said that he knew nothing of her having placed the poison in the basin, nor of her intention to do so. To this statement she persisted twenty times during the day, and on Tuesday she adhered to it in the of the Visiting Justices, who immediately forwarded account it to Sir Guy[?] who, however, said he saw no reason why the law should not take its course. With the exception of the first night after the conviction, the convicts slept soundly, and ate heartily: on the morning of the execution Lucas actually ate a pound of mutton chops for his breakfast. Both behaved with great decorum, and had prepared their minds for the dreadful doom which awaited them. On Friday, the gallows was erected in front of the Gaol; it was almost 18 feet from the ground, and faced the Castle-hill. The petitions in favour of a commutation of the punishment of the criminals were early in the week sent to the Secretary of State, but well-intentioned as were the efforts, we never supposed that they would have any effect. There were two petitions, and both were signed but many very respectable persons refused to sign, stating as their reason, that they believed if punishment by death were abolished, murders would be more frequent; and they instanced in support of their views the rapid increase of the crime of arson since had ceased to visited by punishment of death.

…

A remarkable fact, that a relative of the female, named William Reeder, was executed at our County Gaol the 3rd of April, I830, for arson, in company with two other men for the same offence: and Lucas has two uncles who have been transported. Several humane and pious ladies sought to obtain an interview with Mary Reeder previous to her execution; but they were unable to do so; they stated that they wished read and pray to her but the laws of the gaol are imperative no others, under any pretence, were allowed to see either of the criminals.

[The original of the next section is unreadable on the British Newspaper Archive website. This is the OCR version.]

A very proper regulation. Why should persons, immured within the dungeon walls a prison, waiting, overpowered with mental anguish, or indifferent to their fate, as the case may be, be made a show to the morbid or the curious. On Thursday, the relatives of the culprits went to take last farewell of them. To see Lucas, there were Henry Lucas, his father: Man. Lucas, his mother; Adam Lucas, bis brother ; Jane Lueas, his sister; Elizabeth Lucas, his sister-in-law ; and Sophia Winter&iod, his aunt. To see Mary were, Henry Ileeder, her fuller (her mother dead); Sarah Kecder, her <<ater, the next sister in age; and Jane Kecder, a venagcr sister still. The meeting both sides was affecting in the extreme tears were shed most profusely, and the display of affection at the last grasp of the aud was agonising to behold. The same scene was undergone in female’s ward. The time allotted to the visitors having expired, they left the gaol with tearful and sorrowful hearts. Lucas’s friends did not Mary Kecder, and Mary friends had no interview with Lucas; no wuh was expressed by either psrty that effect. executions were beneficial public morals, in proportion lo their* attraction, few persons would found ra»h enough to them. Tho taking of life wooden scaffold, by the hands of summon hangman, seems to set country, for miles around, in motion, where it is to occur. Thousands of persons flocked into Cambridge on Saturday, from the villages. The roads were lined with vehicles of description, and thousands upon thousands of pedesniTlv A stranger not knowing what was about °»*”ur, might reasonably have fancied that was f**at holiday, or that a famous fair was to lield, »»vtead two wretched culprits about to suffer a horrid crime. The entrance the front of w gateway, and early six o’clock, persons began to Hock in obtain a good position, to •*»«t their upon the quiverings and last agonies of • las Lucas and Mary Keedcr. Even on the previous w visited by hundreds of persons, who ere thither by curiosity, and to fix upon the best witness the execution and the streets of £«*. I-nday night, wer« thronged with visitors from

[The remainder of the scan of the original is readable]

the country, who were determined be in time a rumour having gone abroad that the execution would take place as early as eight o’clock in the morning.

That part the Castle-hill, fronting the drop, gave the appearance of a living mountain, and the sides of the gaol were crammed to suffocation. On the Chesterton, the Victoria, and other roads, in fact all places and all positions where a sight could be obtained of the gallows, were crowds of human beings, waiting and watching with intense anxiety, the moment when the young criminals should submerge from the gaol, and appear under the fatal beam.

A scaffold was erected, commanding a side-view of the scene, about 40 yards from the gallows, by an enterprising landlord, whose premises adjoin, and the charge we hear for those wishing to avoid the pressure of the crowd, and escape all danger, was half-a-crown. Never to our recollection did the streets of Cambridge display such a concourse of people. From ten in the morning up to the hour of execution, Bridge Street, and other places leading to the gaol yard, were almost impassable. Apple and orange stalls are erected at the gaol gate, and the bustle and confusion was most astonishing. A waggon laden with visitors started from Linton as early as four o’clock in the morning, and the cargo of humanity hurried at once to the gaol drop. It was expected that there would be a large importation of pickpockets and other gentry who keep a sharp look out for plunder, on all occasions of this kind, policeman in plain clothes were stationed at the railway on Friday, throughout the day, to watch the persons who came, that a keen eye might be kept upon them if seen, either in the town or at place the of execution. Calcraft, the hangman arrived on Friday night.

It is a difficult thing to calculate numbers under such circumstances, but it may be fairly computed that 30,000 persons were present at the execution. The boats on the Cam, and the Midsummer Common, commanded an uninterrupted view of the scene, and by no means so fraught with danger as the field in close proximity to the gallows. were covered with groups of spectators.

On Friday, by permission of the gaoler, full service was performed at the gaol, and the day throughout was observed as the Sabbath, the culprits being allowed to partake of the Sacrament. ln the evening, the convicts had an interview in the presence of the Rev. Mr. Roberts, to whom they made a lengthened statement, in which Lucas reiterated his innocence, and Mary Reeder persisted that she alone was the guilty party. On Saturday morning the Rev. Mr. Roberts reached the gaol at nine o’clock, and service was again performed; and the Sacrament administered. Both criminals were very thankful to the rev. gentleman for bis constant and unremitting attention them, and for having well prepared their minds for the great change that awaited them.

The culprits were conducted into the pinioning room, where the hangman made the necessary arrangements, previous to the procession to the scaffold. Both culprits shook hands with Mr. Orridge, the gaoler, for his kindness to them since they had been in his custody; and we have it from the Rev. Mr. Roberts, that Mr. Orridge’s attention and kindness to the culprits since they have been in his charge, have been most praiseworthy, as have also been the attention the head turnkey—Mr. Fynn, and others whose duty it was sit up with the male prisoner; the same also may said of Mrs. Morgan, the gaol matron, and the female attendants who had charge of Mary Reeder. Just at twelve o’clock, the gaoler gave notice that it was time to proceed to the drop. Our Reporter observed a striking difference in the personal appearance of both the unfortunate culprits; since the day of their trial, more especially with regard to Elias Lucas, he seemed to have fallen off considerably; his form had become shrunken, and his features haggard but there was yet a calm and softened expression of the face, far different to that exhibited the trial. Mary Reeder was changed also in her personal appearance, especially about the eyes; they were sunken, and very black round the orb, and she seemed several years older than on day of her trial. A Magistrate asked her how she felt, and she replied “Perfectly well and happy, Sir, and I wish you may be prepared to meet your last moments as I now feel to meet mine.”

The Javelinmen, the Under-Sheriff, and the Rev. Mr. Roberts, reading the burial service, preceeded the culprits to the drop. Both walked with a remarkably firm step; Lucas, on his way, nodded, with a smile to a turnkey; Mary Reeder followed, with several female attendants; she, too, displayed a wonderful nerve. Lucas first ascended the scaffold, and placed himself under the fatal beam; Calcraft, who had walked behind him, then pulled the cap over his face, and adjusted the rope, and while he was employed, Lucas said “I am now going to see God.” Mary Reeder then followed, as calm and tranquil as can be imagined, and while the rope was being adjusted round her neck, the Rev. Gentleman oontinned to read. At length he said to the culprits, who were now prepared, “God bless you both!” “God bless you. God bless you,” they both answered, and next moment the fatal bolt was drawn ; a few convulsive movements of the legs and hands was all that was visible. They might be said to have died almost without a struggle.

So soon as the drop fell, shrieks were heard proceeding from the women in the crowd, and it may fairly be said that there were three women to two men in the assembly.

The crowd on the whole behaved with propriety. Previous to the culprits appearing on the scaffold, there was good deal of whistling and noise, such is heard at the gallery of a theatre previous to the commencement play but when the poor creatures presented themselves, there was a dead silence and as soon as the drop fell, hundreds and thousands hurried away from the disgusting scene.

Lucas several time throughout the morning exclaimed “oh how glad I shall be when the time comes and certainly his appearance in his progress to the drop evinced the truth of his remarks. Reeder also said she should be glad when it was all over. There were inside the Gaol several Magistrates of the County, and other gentlemen, who expressed their regret that two beings so young should have brought down upon themselves so awful a punishment. Lucas employed himself during Friday in writing two letters, which we append below; Mary Reeder retired to bed early, and awoke up once towards morning, and, turning to her attendant, said, ” I have a a fearful trial to undergo; I don’t know how ever I shall get through with it when it comes; may God assist me.” She closed her eyes again, and was in minute or two asleep. Lucas, from childhood, had always been respected in the village in which he lived. He worked as a labourer fourteen years previous to his marriage, and invariably during that time carried home all his earnings to his parents, not a farthing of which he had ever returned to him. He supplied himself with clothes by money earned at harvest time and over hours; he was not in the habit of frequenting public-houses but till within the last four years, and previously attended a place of worship. He then connived at the crimes of others, though he received no benefit from them; then he neglected bis Church, and, as he says, became hardened;” he discovered that Mary Reeder loved him fondly, and, instead of checking it, criminal intercourse followed ; but he solemnly avowed, up to the last moment of bis life, that he never knew of Mary’s intention to poison his wife. “Calcraft,” said he, as he was being pinioned, “You are going to hang an innocent man, but I don’t care, I don’t wish to live.” It also true that Mary Reeder, when she implicated Lucas in the crime, never looked the Clergyman in the face; nor did she once raise her eyes from the ground until she exonerated him from any participation in the murder; after that, she would confront the Rev. Gentleman unflinchingly. Lucas was shrewd and intelligent young man; could converse well and sensibly, although his education had been very deficient, as is the case with all agricultural labourers; Mary was not only uneducated, but singularly dull of comprehension, and was looked upon by those who best knew her as a soft, stupid girl, and this was fully borne out by her looks, for, though she possessed regular and pleasing features, she possessed a face as unintelligent as can well be conceived; and from the apathy she evinced at the trial, and her unmeaning looks, ever and anon cast round the Court, it was evident she was thoroughly ignorant and careless of the melancholy and dangerous position in which she stood. She having acknowledged her guilt, there can be no question about it; but, from Lucas’s statements and conduct, backed by Mary Reeder’s, there are many persons who have a very strong impression that Lucas really was innocent, and that his life has been wantonly sacrificed by the same person who sent his wife also to the grave an injured and a murdered woman.

The barricades comprised oak posts with close deal boards round, so that persons composing the crowd could see no one within the enclosure.

The bodies having been suspended an hour, the usual time, they were cut down, conveyed in the gaol, placed in two plain but neat coffins, and buried within its precincts; and what is rather unusual, the Rev. Mr. Roberts read the funeral service over them, the gaol officials standing by. The rev. gentleman stated that he never before saw a man so prepared meet his fate and die. He seemed thoroughly happy, and in the confident expectation of a life of glory, through the merits of a crucified Saviour; Mary Reeder, too, had also, since her condemnation, evinced great penitence, and appeared fully prepared for the great change that awaited her. Great was their crime; but terrible, on earth, has been the retribution.

It is impossible to form too high an estimate of the conduct of the Rev. Mr. Roberts: he generally spent between six and eight hours a day with the culprits, and enlightened their ignorant minds upon the subject of religion ; hence from the manner in which they met their fate, it was evident that he had first plucked away the sting of death. Indeed, so fully prepared were they at the last, that Lucas, on being pinioned, said, “I would not be reprieved if any one would give me £10,000!” Lucas was dressed as was at the trial; he wore a sleeve jacket, cord breeches, and drab garters: he looked a young, strong, active labourer. Mary was dressed in humble attire: she wore a light-coloured blue cotton dress, and a neat cap; but she wore no stays. On her arrival under the beam, Calcraft pulled off her cap and put his own on, but it did not come lower than her mouth. The cap over Lucas’s face covered his chin. When the drop fell his eyes were open (as seen through the can), and cast up Heaven. Reeder’s eyes were closed; indeed, she scarcely looked up from the ground from leaving the pinioning-room till she reached the scaffold. On being taken down, the countenances of both criminals had undergone little or no change ; that of Reeder’s looked as complacent as though she were asleep.

[The following section is unreadable on the scan of the original]

The following is prayer delivered by the rev. gentleman while the convicts were on the scaffold:— i O blessed Lord God, Thou that hcarest the prayer, and uuto whom all flesh shall come, accept, we pray Thee, these few last words of prayer for these thy dying servants, and hope, for Jesns Christ’s sake, pardoned and redeemed sin; ners. not angry with us, O Lord, for the judgments of our law, wliich we believe to be founded upon thy divine , and written law; and lay not their blood to our charge, but i spare them, O Lord, and deliver them from the bitter pains of eternal death. Make, we beseech Thee, this death their bodies upou the scaffold the door which opens unto everlasting life; inay they pass through the valley and , shadow of death and fear no evil, but find Thee to with ; them as their Guide and Conductor to the realms of ever| lasting peace and joy; may they die in forgiveness of their ‘ fellow-man and at peace with all the world, praying for every one who has offended them without a cause*, as for those who have been the means. In Thy hands to bring them to this condemnation—and as not a sparrow falletbto the ground without Thy knowledge—so can n« human creature depart this life without Thy heavenly will and sanction. Forgive Thou them, dear Lord, forgive them for Je»us Christ’s sake, and receive their sonls into thv presence; for into Thy hands do we, O Lord, commend them, since Thou bast redeemed them, O Lord Thou God of Truth.— Amen. Th« following are verbatim copies of two letters written by during the night; one being addressed to the prisoners io the gaol ; the other to his parents : [corf]. “Cambridge Castle. Parents,- Tliis is the !a*t time that ever shall communicate to you m this troublesome world, but I hope that 1 go to rest in God above. Dear brothers and sitter, and my beloved child, my own flesh and blood, but if

[The following section is readable from the scan of the original]

trust in God He will bring all things to pass. Remember, when are we are left without God for a time, O how soon will Satan bring evil upon any of us. Dear friends – be sure our sins will find out sooner or later; but what I say unto you, set your house in order, for you must die, and not live. Think of your immortal soul, which will perish or be saved. Therefore, watch, for ye know not the hour in which our Lord cometh; therefore be ready to meet thy Saviour, when He cometh to call the lost sheep which are lost in sin. You, my dearest and beloved parents I am afraid you will perish, except you repent ; but bless God for blessing me to see my own shame and misery which I have brought on myself, and I could not have seen without my Saviour’s grace. But bless God for showing me His grace. So, dear parents, be like unto Job; bear the Lord’s will with patience. Look at the troubles of Job —he lost bis family, and all that he had, and he blessed — and naked came I out of my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return. So shall I return thither to a land which I now know not. My soul will soon be on its journey into place of departed spirits, and you must soon follow. Soon will your departure be hence; the Iargest of you must prepare for eternity. Oh, how awful is these words – Eternity! Eternity! my dear parents! let this sink deep into your hearts. Soon must I pass this gloomy vale, and in my last expending breath his sovereign goodness sing. Let this sink deep into your heart, when you read this. Press this on your mind and pray to God to keep you from sin; for remember that the eye of God is on you all – on all your evil deeds, and spieth out all your ways. Be sure you cannot hide from God, though you may from man. Remember you are travelling to the grave. Listen to the Bell which you dear father sp often toll. How awful is the sound to those who are unprepared to the call of God. Dear friends, in a few more days will it go for you. Remember dear father, when you do this, let this touch your rocky heart and think that the next time it. may usher your soul into the presence of an heavenly judge. Dear friends I hope to meet death with pleasure, and bless that heavenly messenger to take me from this world of snares and sorrow and temptations. into a world of pleasure and comfort, there to have no end, where tears shall be wiped from our eyes, and sorrow shall be no more. remember this comes from the lips of a dying sinner, But you have moses and the prophets. neither will you believe me till Destruction cometh upon you as a sorrow upon a woman in travel with child, and you will not escape. But I am in hopes of a better world above i am in hopes that God has pardoned my sins and wickedness before i go hence through Jesus Christ my Lord. My Dear Parents that this may Be your happiness is the Last prayer of your dying son. Elias Lucas. Kiss my dear child. Saturday morning 3 o’clock, April 13, 1850.

From My Cell, Friday Night, 12 o’clock

My Unhappy Fellow Prisoners, – l have termed you unhappy, because I have been in this place long enough know that happiness to you is an entire stranger. Alas, how far have we wandered from the paths of happiness, into the broad road that surely leads to everlasting death. As a dying man let me entreat you to consider where the path leads to in which you are now treading. Is it to the joys of Heaven, or to that place where there is weeping and wailing and gnashing of teeth? Soon you will be at the end of your journey. Alas, how soon is my journey ended! In twelve short hours, I shall no more but thank God that I feel (though a wicked sinner) calm and resigned to His will, and fix all my hopes of salvation upon the merits of Jesus Christ alone. My heart was hard indeed, but not too hard for God to melt with his mercy; a broken and contrite heart are not despised by Him, and the angels in Heaven rejoice over a repenting sinner. I have felt sins a heavy burden, and have, by grace, been led to ask for mercy for Jesu’s sake and I am glad to tell you, my once fellow prisoners, that I, who feel myself the vilest of all sinners, have a hope in God’s mercy. I deserve eternal death, yet I hope for eternal life. I, by the time you receive this, shall be no more on earth; you are still in the land of the living; live as if you had immortal souls. Oh, how differently should my time be occupied, if I were allowed still live. But I will not mourn, but thank God that he has stopped me in my career of crime, and given me a hope that I shall with joy see His face above and with my dying breath I pray this may the case with you. ‘Except ye repent you must all perish,’ and know and feel the bitter pains of eternal death. Turn away, then, from the miserable paths of sin; receive this a voice from the dead; and when, my unhappy fellow prisoners, we meet again may it be with the happy spirits of those who are the children of God in heaven. I feel comfortable in looking forward to a happy eternity, and when you receive this, I shall be no more your fellow, prisoner, Elias Lucas

THE CONDEMNED SERMON

Preached by the Rev. Horace Roberts, on Sunday last, at the County Gaol.

“There is joy in the presence the angels of God over one sinner that repenteth.”— St. Luke xv. 10.

These words have no imaginary person for their author. | They are neither founded on speculation, nor are they uttered without an assurance of their truth. When, therefore, we quote them (as on this solemn occasion) for a text on which to found the doctrine of repentance and everlasting life, we naturally regard their meaning as full of comfort to the afflicted, hope the condemned, and encouragement the wayward. We remember that He who declared these words “spake as never yet man spake.” Heaven was to Him a home — a blessed and a happy home, where he had seen and known from all eternity its joys, its blessedness, and glory. Though on earth He was a man of sorrow and acquainted with grief, yet every act and every miracle, as well as every word, confirmed the fact that He was more than human; that the divine power of an Almighty God reigned within Him, and that, in consequence, all things were at His command, so that even “the wind and the waves obeyed Him.” As we know the character of all things here on earth — the causes of joy and causes of our sorrow — the happiness or misery of our respective homes — so did Jesus know all that occurred in heaven, where sorrow, He has told us, never enters — where tears are wiped from off all faces — where live ” the spirits of just men made perfect” — and where “there is joy in the presence of the angels of God over one sinner that repenteth.”

The parable which forms the prelude to these words our Lord explains in allusion to the earnestness with which all of us regard our temporal interests and welfare, and as (says He) the shepherd will leave 99 of his flock to seek after one strayed sheep, one woman will look diligently after the one piece of silver out ten which she loses, and both will rejoice more over the recovery of the lost than in retaining the possession of that which they have; so will there be more joy in heaven over one sinner that repenteth.

Now, repentance in this case may not only be taken to mean a change or reformation during the remainder of our uncertain life, but may apply to that which our unfortunate fellow-creatures may evince whose crimes the laws of their country have determined must be expiated on the scaffold. Repentance is a thorough change of heart and mind — an adoption of a course of life widely at variance with that which has hitherto been observed. And though it is true that when once the sentence of the law has been passed, and a death decreed on by the a public executioner, and consequently a premature death, no further opportunity can be granted for a conflict with the temptations of the world; yet, even in the dungeon of the condemned, there may be unholy thoughts — there may be worldly feelings and reflections, and there may be a deadness to spiritual impressions, whereby the door of repentance is closed, and the light of grace excluded. Thankful, then, must we feel if we can, by the glimmering light of faith, see in the outward professions and actions of the doomed true penitence for past transgressions, a godly sorrow ” which worketh repentance with salvation not to be repented of” — a sincere dependence eternal mercy – eternal love and goodness, manifested by the eternal God for the forgiveness of man’s sins. And oh! may those outward symptoms of contrition which I have beheld (I may add with joy) be but the forerunner of a hope to abide with you; yea ! to abide with all of us, that when these our brethren in nature and redemption shall be no more — when the fell judgment of the law shall have been executed, and their lives have paid the penalty of their crimes, we may rest assured that they are gone to a better and a happier world. A death on the scaffold is no sin. It is sin which brings that kind of death; and although the evidence of man — the combination of human circumstances — may be to us (who regard the claims of justice as we respect the good and wellbeing of society in the world) an overwhelming testimony of the truth that it be the finger of Almighty God which points out to us those who have offended Him — have violated His laws — transgressed His commandments, and prejudiced the salvation of their own undying souls — yet, to Him, however, “belong mercies and forgivenesses;” and while the attributes of justice, both human and divine, are exercised, where man cannot spare God can reconcile; where man cannot forgive God can pardon and receive; and where the gate of human mercy must be closed against our fellow man, the Son of God, in Jesus Christ, withdraws the forbidden barrier of man’s compassion, and opens wide the door which leads to life eternal. We may pour forth our prayers; we may join as brethren our requests to Him who lives, who rules, who reigns above. There shall we find a ready ear; there shall we meet with that assurance which the penitent and the faithful may rejoice to know, and which Almighty grace and love may teach them to be an assured reality in answer to those supplications and entreaties which we make ” The Lord hath heard our petition and will receive our prayers.” We may weep for the misfortunes two so young, so misguided and so sinful;

[The scan of the original text of the sermon is illegible from now on.]

1859

1861

Augustus Hilton of Parson Drove was hung here on 10th August for the murder of his wife.

1863

The hanging of John Green for the murder of Elizabeth Brown at Whittlesey in 1862

1870

On how prisoners were treated in Cambridgeshire County Gaol in 1870

Edwin Bays (1843 – 1909) was the Clerk of Works and the apprentice to Mr William Milner Fawcett, the architect, for the renovation works between 1868 and 1870.

1878 became a state prison

1898 Execution of Water Horsford 28th June. See East Street, St Neots.

Back row from left: A Hills, W Collins, H Dobbs, J Collinge, H Bentley, F Pullen

Middle row: H Andrews, E taylor, Miss Mapston. Miss Woods (Matron), Miss Anderson, C Styles, E Carter

Front row: Mr Pead (Chief Warden), Mr Croxall (Clark and Schoolmaster), Rev F Hird (Chaplain), Dr Ezard (Medical Officer), Rev. H Whitehead (Deputy Chaplain)

4.11.1913 the last person to be executed at the gaol, Frederick Seekings, was hung by T W Pierrepoint.

1916 ceased to be prison and used to store documents.

1928 County Council took over the premises

1930

It was demolished soon after this.

1956 – 1986 Much of the housing on Castle Hill was demolished allowing access for archaeological investigation to take place. The results of this were published in CAS 1999 report: Roman Cambridge: excavation on Castle Hill 1956 – 1988 by John Alexander and Joyce Pullinger.

1968

For plans of buildings that never happened on Castle Hill see:

Sources include:

Cambridge Castle by W M Palmer, 1928

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0