Search by topic

- archaeology

- architecture

- bricklayer

- Building of Local Interest

- carpenter

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- listed building

- medieval

- oral history

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

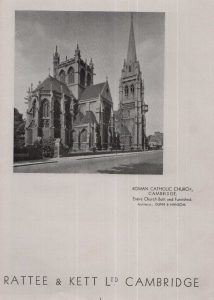

Our Lady and the English Martyrs (Catholic Church)

History of Our Lady and the English Martyrs

According to Pevsner, the church was built 1885-1890 by Dunn and Hansom of Newcastle. It was paid for by Mrs Lyne-Stephens, as the parapet inscription proclaims. She was formerly Yolande (Pauline) Duvernay, an operatic dancer; it was alleged at the time that her late husband’s fortune came from patenting dolls’ eyes that could move. In fact, the family wealth had come from two Portuguese glass factories. In its time the church was a controversial assertion of the Catholic presence in Cambridge.

See also chapters 8 in ‘Catholics in Cambridge’ ed.Nicholas Rogers.

Mrs Lyne-Stephens insisted on bearing the entire cost of the church and its furnishings and likewise the rectory, totalling in all over £70,000. One exception only was made, that of a restored medieval processional cross given by Baron Anatole von Huegel, a faithful supporter of Canon Scott from the latter’s earliest years in charge of the mission.

For a detailed account of the story of Pauline Lyne-Stephens, see Mary Greene’s autobiography, The Joy of Remembering.

More information about Stephen Lyne-Stephens can be found here.

Edward Conybeare wrote about the time of the building of the church:

Though a generation or more passed since Catholic Emancipation, the penal laws … were still remembered and some non-Catholic considered that a religion so recently … outlawed ought to avoid making itself conspicuous. Yet the new church was the most outstanding landmark in the whole town. Hostility was thus aroused; shoals of letters, of bigotry now almost unthinkable, were sent to the local Press, and the great poplar tree which stood at Hyde Park Corner was white with ultra Protestant posted and leaflets…

Saturday 11 October 1890, Cambridge Independent Press, p.5. An article anticipating the opening of the Church.

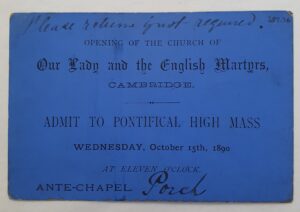

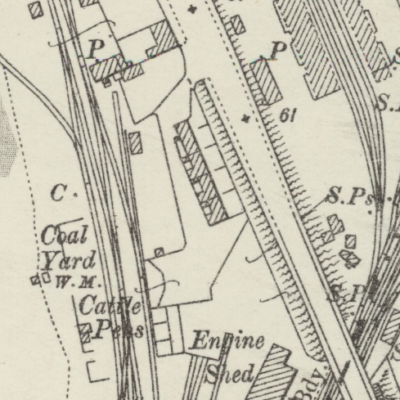

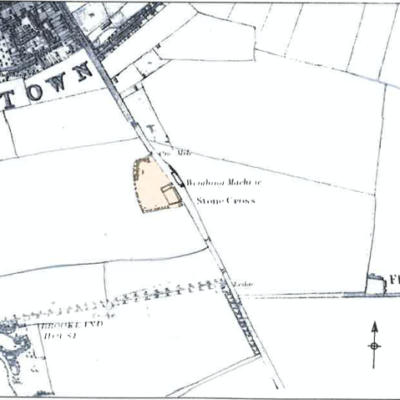

The beautiful edifice situated at the corner of Lensfield Road, which has been so long course of erection, was dedicated on Wednesday morning by the Bishop of Northampton, in the presence of a large assembly of clergy and laity of the Diocese. It is now three years since the ceremony of laying the foundation stone was performed the Bishop of Northampton and the Revs. E. J. Watson and R. Pate. A better site for the Church it would have been impossible to have chosen. It is situated on a slight eminence, and has the advantage of being in the main thoroughfare of the town. The site was formerly known as the Lensfield Estate, and it was purchased at cost of about £6,600. of which sum the Duke of Norfolk, whose benefactions are known all over England, was responsible for £3,000. The house occupied by Canon Scott, the bead of Cambridge Catholicism, was demolished in order to make room for the Church.

Cambridge Inscriptions Explained by Nancy Gregory (2006) looks at the background to the inscription over the Lensfield Road portal:

Fecit:Mihi:Magna:Qui:Potens:Est

He who is powerful has done great things to me

Ave Maria gratia plena Dominus tecum benedicta tu in mulieribus et benedictus fructus ventri tui Jesus. Sancta Maria Mater Dei ora pro nobis peccatoribus nunc et in hora mortis nostrae Amen

Hail Mary full of grace: the Lord is with thee: Blessed art thou among women: and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus: Holy Mary, Mother of God: pray for us sinners now and in the hour of our death.

Pray for the good estate of Yolande Mar[ie] L[oui]se Lyne Stephens foundress of this Church

E.M.Forster, the Longest Journey, 1907:

They wait for the other tram by the Roman Catholic Church, whose florid bulk was already receding into twilight. It is the first big building that the incoming visitor sees. ‘Oh, here come the colleges!’ cries the Protestant parent, and then learns that it was built by a Papist who made a fortune out of moveable eyes for dolls. ‘Built out of dolls’ eyes to contain idols’ – that, at all events, is the legend and the joke. It watches over the apostate city, taller by many a yard than anything within, and asserting, however wildly, that here is eternity, stability, and bubbles unbreakable upon a windless sea.

For information about Robert Hugh Benson, curate 1905-8.

1922 23rd February: Funeral of Monsignor Christopher Scott.

Monsignor Canon James Bernard Marshall, rector 1922 – 1946. After a career as a barrister he was ordained a priest in Rome on 27th February 1915. He then spent three years on the Western Front with the 21st Division during WWI, being appointed Senior Divisional Chaplain in 1917, receiving the Military Cross and a mention in dispatches. In 1918 he was invalided home and posted to Cambridge as the joint Catholic Chaplain to the Military Hospitals, the Officer Cadet Corps battalions in Cambridge and the remaining undergraduates in the University. He was demobilized in 1920 with the rank of Honorary Chaplain to the Forces and after four years as University Chaplain 1918-22 he was appointed rector of OLEM following the death of Canon Scott. (see Catholics in Cambridge , ed. N Rogers)

World War II (information from Catholics in Cambridge p.178f)

The church faced the problem of many Catholic children scattered over Cambridgeshire with limited opportunities to attend Catholic schools or churches or even to be placed with Catholic families. The clergy faced a particular problem with the black-out regulations; the windows of the church were far too high and large to be covered, and the rectory had very many windows as well. Services continued at the usual times but candles were the only source of light.

When it came to Midnight Mass in 1939 it was expected that this service would be cancelled in all Catholic churches. However the Cambridge Chief Constable saw no objection and so, whilst generally banned across the country, five Midnight Masses took place in Cambridge.

The school, designed for 220, never had less than 260 on its role, 60 of these evacuees. An extra class was formed and an additional teacher, Miss Ethel Grady, was supplied by the London County Council to help.

During the war the church was visited by large numbers of Poles, French, Belgians, Czechs, Canadians and Australians. Large contingents, such as US forces, brought their chaplains with them and Masses were heard in the military camps, but for special occasions many still came into Cambridge for the church.

On the 2nd May 1943 during Anglo-Polish Week the Polish President in Exile visited, Ladislas Raczkiewicz. In July 1943 the death of the Polish commander General Sikorski was marked by a sung Requiem Mass. A few days later the French marked their national day at the church.

Cambridge was also the home for evacuated institutions such as London University, Ministries and shadow factories. There were imported labour forces including a large one from Ireland; Dublin was concerned that these workers were kept together so a Sunday Social was started in the Houghton Hall and strictly limited to Catholics, whether civilian or military from any country. The entertainment started after the evening service at stopped at 10pm with prayers for peace. 3500 admission cards were issued during the war. There was also a weekly ‘Forces Party’ organized by the Catholic Women’s League. The Catholic Men’s Club started to admit new members and over 1270 servicemen signed the special Forces Register.

One side product was all this was the extra revenue. In particular because of the generosity of visiting American forces all the debt that had accumulated during the building works of the 30s, some £6500, was entirely cleared by 1945.

Other groups needed some special treatment. German and Austrian refugees were looked after by the Canonesses of St Augustine. There was also a large contingent of Italian prisoners of war in a camp just outside Trumpington. Canon Marshall’s niece, Molly, was a fluent speaker of Italian and she organised social gatherings in the Houghton Hall on Sunday afternoons with music and refreshment provided by ladies with some knowledge of Italian. Classes in English were organised in the POW camp.

Ironically, the fact that Mass was said in latin was an advantage since priest could officiate for any nationality. Canon Marshall was able to sing a High Mass with two Polish priests in support.

One rule which had to be relaxed though was that of the eucharistic fast. It was expected that those receiving Holy Communion would have fasted since at least Midnight and that they would receive fairly early on a Sunday morning. However, American servicemen who were flying overnight missions had been given dispensation from the eucharistic fast, and Italians had also been given dispensation for the duration of the war. This was made rather obvious one morning when a lone American serviceman approached the altar rail one Sunday morning while the rest of the congregation remained in their seats.

With regard to enemy action, there was a raid on Cambridge on the night of 23-24 September. The target, the station, was missed and although lots of windows were broken the church glass escaped.

On the night of 16th January 1941 250 incendiary bombs were dropped in a close pattern centred on Hyde Park Corner. Some of the bombs slithered down the southern roof of the church but did not cause a fire. The main damage happened to the hall of the Perse School opposite and Flinders’ electrical store at 91 Regent Street.

The most serious raid was on 24th February (Shrove Tuesday) 1941 when German bombers flew in very low and made a concentrated attack on the section of Hills Road between the church and the war memorial. Ten were left dead, mainly at The Globe and Bull’s Dairy. An important consignment of tanks was being unloaded that night at the station and the precision of the attack has fuelled rumours ever since that the Germans had intelligence, possibly from the agent Jan Ter Braak who was known to have been operating in Cambridge at the time. At 11pm a 50kg high explosive bomb exploded on the roof of the sacristy; it blew a six foot hole in the roof and a similar sized hole in the wall of the Sacred Heart Chapel. All the windows of the apse were blown out and most other windows in the church damaged.

Canon Marshall wrote an account of the clear up operation, the creation of a temporary altar and makeshift sanctuary. Molly Marshall, his niece, wrote:

Whenever the alert sounded at night Canon Marshall would get up, put on his steel helmet and walk the streets of Cambridge with his dog Billy, hoping to be on hand if any of his parishioners suffered in an air raid. It was fortunate for him that he was out on the streets when the church was hit by the bomb on Shrove Tuesday 1941.

Margaret Plumb (Catholics in Cambridge p.220) describes life as a child during WWII both in the school and the church, in particular the annual Corpus Christi Procession.

Edmund Harold Stokes was appointed parish priest in 1946.

For the role of the church in the life of Gerri Bird, Mayor of Cambridge, follow link.

General information about the church can be found on Wikipedia.

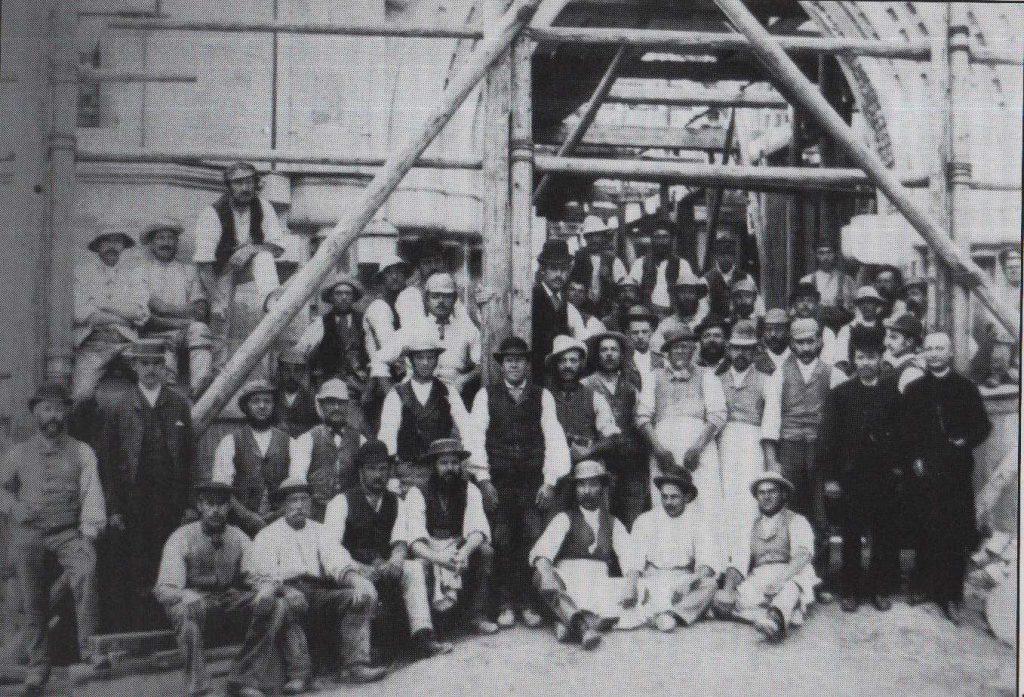

Rattee and Kett completed the construction of the Catholic church in 1890. The photo is of their workers.

2021 Christmas Day

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0