Search by topic

- archaeology

- architecture

- bricklayer

- Building of Local Interest

- carpenter

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- listed building

- medieval

- oral history

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

3 Hooper Street, Jubilee House (Edinburgh House)

Infirmary for the Leys School

Jubilee house is a tall and imposing detached house in Hooper Street, with ancient horse chestnut trees in its forecourt. Until at least the 1960s it was called Edinburgh House, and it has served as an orphanage (briefly), the infirmary for the Leys School and as a nurses’ home.

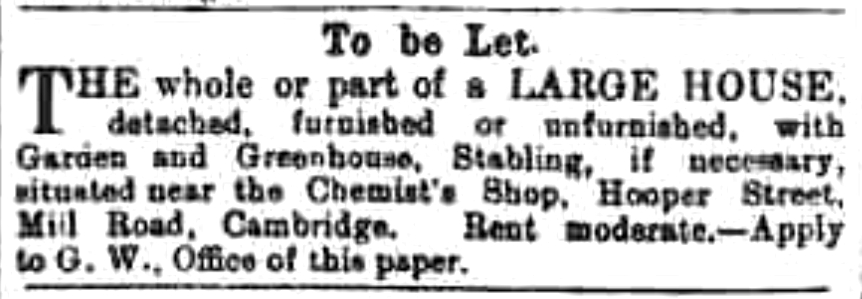

In spring 1877 the property was advertised to let for May Term in the form of furnished apartments. In the autumn it was advertised again (Cambridge Chronicle, 29 September 1877):

The 1881 and 1891 census records have entries for 1 and 2 Hooper Street, numbers that were not subsequently used. The first inhabitants of no. 2 – a wealthy family in 1881 and a caretaker and a nurse in 1891 – suggest that it was the original number used for Edinburgh House. No. 1 may refer to 138a Gwydir Street, which is not mentioned in the 1881 and 1891 census records.

1881 census (1 Hooper Street)

Henry Grover, 54, police constable, Great Eastern Railway, b. Cripplegate Parish, Middlesex

Harriet Grover, 37, b. Vizagapatam, India

Lawrence H. Grover, 12, scholar, b. Ootacamund, India

William John Grover, 9, scholar, b. St Bartholomew’s, Middlesex

Henry Grover was a police constable on the railways, and in later census records he is listed as an army pensioner. Henry was born in central London in 1827 and in 1846 he joined the 19th Regiment of the British Army, and served in the Mediterranean, the West Indies and India before being discharged in 1869 after 21 full years’ service. His service record suggests that he arrived in India in the immediate aftermath of the Indian Mutiny in 1857. His discharge papers tell us that he was just under 6ft, with a fair complexion, hazel eyes and brown hair.

In 1862 he married Harriet Maker. Harriet was born around 1844 in Vizakhapatnam, southern India. The India Office records are patchy, but there are several military and ecclesiastical records for ‘Maker’ in the Madras Presidency in the early nineteenth century. Henry and Harriet’s son Lawrence was born in India, and they had an older son Henry born in India, who had left the family home by 1881 and was working as a servant in Brighton.

By 1891 Henry was lodging in London with his youngest son William (a railway worker) and Harriet was lodging in Cockburn Street, Cambridge, ‘supported by husband’. In 1892 Henry spent four months in Cambridge Gaol for unlawfully and indecently assaulting a 9 year-old girl. He gave her a penny and told her to keep quiet about it, but she had the sense and courage to tell all to her mother, who called the police (Cambridge Independent Press, 8 April 1892). His army pension was stopped for those four months.

By 1901 Henry and Harriet Grover were living on Henry’s army pension in Caterham, Surrey. Their middle son Lawrence was still in Cambridge, living in Perowne Street with his wife and family and working as a French polisher.

1881 census (2 Hooper Street)

James West Knights, 27, analyst, consulting chemist, b. Earith, Huntingdonshire

Margaret E. Knights, 30, b. Bishops Stortford, Hertfordshire

Harold James Knights, 9 months, b. Cambridge

Harriet Gray, servant, 21, cook, b. Chesterton, Cambridgeshire

Louisa E. Chambers, servant, 15, domestic nursemaid, b. Bottisham Lode

James West Knights was an analytical chemist, who in later census records is listed as working for the County Council. His father, also James, was a prosperous miller in Hemingford Grey, and James junior had the opportunity to study pharmacology. Margaret (née Ley) was the daughter of a solicitor from Bishop’s Stortford. In later census records they lived in Warkworth Street and St. Barnabas Road.

The local newspapers carry many adverts for James West Knights’ services: analysing food, drugs, milk and in particular water, which he would assess for potability and suitability for brewing and other purposes (e.g. Cambridge Chronicle, 8 May 1880). This was essential in a neighbourhood that saw several outbreaks of water-borne diseases in the late nineteenth century. The situation improved with the building of the sewage pumping station at Riverside in 1895.

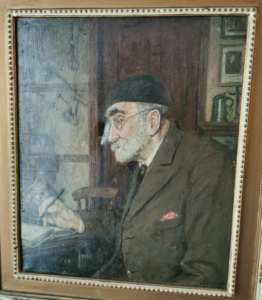

James West Knights (1854 – 1929) Public Analyst for Cambridge (1881 – 1927) by Lillian Edwards (1869 – 1952) © Museum of Cambridge

See 67 Tenison Road for obituary

The Home for Fatherless Boys

A newspaper article of 1888 reports on a bazaar at the Home for Fatherless Boys (Cambridge Chronicle, 18 May 1888): ‘The Home, in behalf of which the bazaar was held, was instituted by the Rev. A. A. Avann, on March 21st, 1887, to meet the special needs of St. Matthew’s parish. The house in which the Home is carried on is Edinburgh House, Hooper Street, Cambridge, where the boys receive their board and clothing, being educated at the York Street Higher Grade School. There is also a small workshop attached to the Home, which is used by the boys chiefly for the purpose of recreation.’

Rev. Arthur Alfred Avann was a young deacon at St. Matthew’s church who tirelessly promoted cultural and sporting activities – the St. Matthew’s Musical Society, the Albert Institute Boat Club – to bring enlightenment to what a former vicar described as the parish’s ‘dull, cheerless streets’. In 1890 Rev. Avann left Cambridge for the curacy of Cockley Cley in Norfolk. The fate of his orphanage in Hooper Street is unclear, but it may have proved the worth of Edinburgh House as a social institution rather than as a private house.

1891 census (2 Hooper Street)

Rebecca Carter, sister, single, 45, caretaker, b. Melbourn, Cambridgeshire

Mary A Newett, sister, married, 36, domestic nurse, b. Melbourn, Cambridgeshire

The occupations of Rebecca Carter and Mary Newett (caretaker and nurse) strongly suggest that 2 Hooper Street was Edinburgh House, perhaps now functioning as the infirmary for the Leys School. Rebecca and Mary were born in Melbourn, daughters of a farm labourer.

In that year, 1 Hooper Street was unoccupied.

1901 census (Edinburgh House)

George Flack, 71, caretaker, b. Sible Hedingham, Essex

Henrietta Flack, 60, matron and teacher, b. Broughton, Huntingdonshire

Alice Jacobs, visitor, 48, b. Woking, Surrey

Emma Frost, visitor, 44, trained nurse for sick, b. Rochester, Kent

Charles Lissant Jacobs, visitor, 15, b. Guildford, Surrey

1911 census (Edinburgh House)

George Flack, 81, caretaker, b. Hedingham, Essex

Henrietta Flack, 71, caretaker, b. Broughton, Huntingdonshire

George Flack was born in Sible Hedingham, Essex, and his wife Henrietta was from Broughton near Huntingdon, but they were not newcomers to Cambridge: in 1881 they lived at 28 Ainsworth Street with George’s teenage son George, a confectioner’s apprentice.

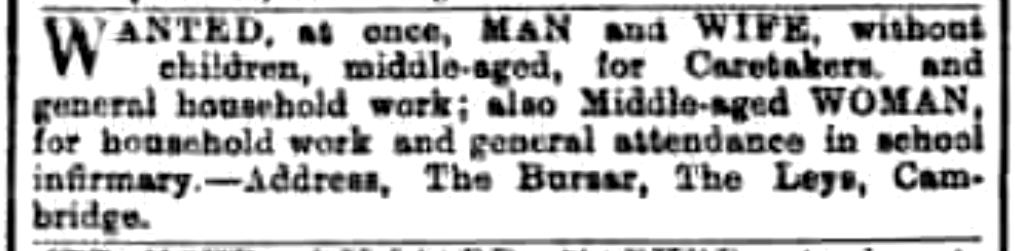

At the time of the 1901 census they may have been newly appointed as caretakers for the Leys School infirmary, or perhaps on probation, as the Cambridge Daily News was still carrying the advert for their jobs several weeks later (18 April 1901):

George Flack died aged 80 ten years later, just a few months after the 1911 census, but Henrietta was still working as the Leys School infirmary matron in 1913, according to Kelly’s street directories.

1921 census (4 Hooper Street)

Robert William Tunmore, head, 41, caretaker for Governors of Leys School, b. Coltishall, Norfolk

Mabel Ellen Tunmore, wife, 34, caretaker for Governors of Leys School, b. Cambridge

According to Spalding’s street directory, by 1924 Edinburgh House had become the Board of Guardians Nurses’ Home, and by 1934 the County Infirmary Nurses’ Home.

1939 England and Wales register

In 1939 the inhabitants of Edinburgh House were Reginald Keene, a relieving officer, and his wife Lilian.

In Spalding’s street directory for 1939, Edinburgh House was the office for Cambridgeshire County Council Public Assistance. By the early 1950s it was used for the County Council’s Youth Employment Service.

1959–1978

KC contacted the Museum in 2021 with the following reminiscences:

I moved to Edinburgh House as a young child with my family in 1959 and we lived there until about 1978 or maybe a bit longer. I have such happy memories of living there and often wondered about who had lived there before. We rented ‘The Flat’, which was the top two floors, attic and half of the cellar. We also had sole use of the whole garden which was huge! The rest of the house was offices for The Youth Employment Office, later to become the Careers Advisory Service.

All the rooms had servant bells and fireplaces and in the cellar there was a servant call board to all the rooms. When we first lived there the house had huge wrought iron gates and railings at the front. The horse chestnuts used to reach up to my bedroom on the top floor. In the garden we had a huge Mulberry Tree which was said to be one of two in the City, the other being in the Botanical Gardens. We frequently picked them and had Mulberry pie. I used to take the leaves into school for the silk worms we kept in the Science Lab!

Sources

UK census records (1841 to 1921), General Register Office birth, marriage and death indexes (1837 onwards), the 1939 England and Wales Register, electoral registers, Kelly’s street directories, and local newspapers available via www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk.

British Library India Office records available via www.fibis.org: 1862 marriage of Henry Grover and Harriet Maker N/2/43 f.207; 1863 baptism of Henry J. Grover N/2/44 f.179; 1868 baptism of Lawrence Grover N/2/2 f.143.

Henry Grover’s Royal Hospital Chelsea Pensioner Soldier Service Records are available via www.fold3.com.

In 2024 the St Clement’s church online newsletter, Dearly Beloved, published an account by Robert Van de Weyer of the recent history of Jubilee House. The following is taken from that article:

By the 1970s the ‘Tech’ (which later evolved into Anglia Ruskin University) had acquired the use of the building, and turned it into classrooms. In 1977 I gave my first lectures there: Economics for day-release trainee accountants. One problem was that the tables and chairs were so crammed that it was impossible to clean underneath them. So the classroom floors became covered by a rising tide of crisp and chocolate packets.

In the stone portico of the house is inscribed the name ‘Jubilee House’. Neighbours and passers-by may think the name celebrates one of Queen Victoria’s jubilees. But the dates don’t fit: the house was built too early.

In the 1980s the house was taken over by an organisation called the Jubilee Centre, led by a remarkable man called Michael Schluter. The ‘Jubilee’ in the title refers to the Jubilee Year in the Bible. This occurred every fiftieth year. Debts were forgiven, and land purchased since the last Jubilee was returned to the original owners. It was a remarkable device for preserving a degree of economic equality. The Jubilee Centre is a think-tank, concerned primarily with the connexions between public policy and personal relationships – with the Bible as the basic source of inspiration. The Jubilee Centre’s greatest success, albeit only partial, was the Keep Sunday Special campaign. In 1985 the Thatcher government proposed the abolition of the laws which prevented most shops from opening on Sundays. The campaign succeeded in watering this down to restricting opening on Sundays to only six hours. This six-hour restriction persists – all thanks to the Jubilee Centre. And people and shops alike seem content with it.

In the meantime, the Jubilee Centre has moved to other premises in Cambridge and Jubilee House has been refurbished as up-market student accommodation.

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0