Search by topic

- archaeology

- Building of Local Interest

- charity

- church

- crime

- dressmaker

- fire

- Great Eastern Railway

- Listed building

- Mapping Relief

- medieval

- oral history

- poverty

- Public House

- Rattee & Kett

- Religious House

- Roman

- scholar

- school

- Then and Now

- tudor

- women

- work

- world war one

- world war two

Search by text

23 Hooper Street, Florence Villa

Florence Villa, 23 Hooper Street

Florence Villa is a large house on the corner of Ainsworth Street and Hooper Street, now with a door only on Hooper Street. It carries a plaque reading ‘Florence Villa 1870’. It was originally numbered 23 Hooper Street but had become known as 110 Ainsworth Street by 1891. In 1930 it reverted to 23 Hooper Street.

For many years, from the 1870s to the First World War, it was a beerhouse, the Great Eastern Tavern. There were many pubs in the neighbourhood because the water was dirty and carried diseases such as cholera and typhoid. Beer was safer to drink, as the water had been boiled and thus sterilised. It was common for young children to drink weak beer for this very reason, called ‘small beer’, hence the saying that something insignificant is just ‘small beer’! Beer (and spirits) licences were granted by the Borough Council, and took careful account of the projected population of new neighbourhoods.

There were still outbreaks of water-borne diseases in this area throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The situation was only improved with the building of the sewage pumping station at Riverside in 1895, and the Bath House on Gwydir Street, providing better sanitation to Sturton Town residents.

1871 census for households 232 and 233*

Mark Almond, head, 45, milkman, b. Great Bentley, Essex

Harriet Almond, wife, 42, b. Wisbeach, Cambridgeshire

Florence M Almond, niece, 7, b. London, Middlesex

James C Yerman, head, 22, railway guard, b. East Ham, Essex

Mary Yerman, wife, 25, b. Gayton, Norfolk

Elizabeth Creed, visitor, 66, nurse, b. Snettisham, Norfolk

*In 1871 Ainsworth Street was not yet numbered. Identification of houses is tentative. The house containing households 232 and 233 is the last one listed in Ainsworth Street.

Deeds held by owners of this house and its neighbours suggest that Mark Almond was the original property developer and owner, and that he also owned and developed 100–108 Ainsworth Street and the plot of land between the houses and the railway, now 23A and 23B Hooper Street. His occupation as milkman in 1871 suggests that he kept cows on the land. The house was very likely named after his niece (and adopted daughter) Florence. Nonetheless, in 1871 the house was occupied by two families, suggesting that he had to let out the upstairs or downstairs to make ends meet.

In 1871 he was granted a beerhouse licence, permitting him to serve beer, cider and perry (Cambridge Independent Press, 30 September 1871); he named it the Great Eastern Tavern. He did apply for a spirit licence to convert the tavern into a public house, but this does not seem to have been granted. It is referred to specifically as a beerhouse in the 1879 Post Office directory, and similarly in the 1910 land tax records. In 1874 Mark Almond sold the beerhouse, along with the plot of land behind it, to brewer Frederic Freeman, whose business was taken over by the Star Brewery in 1903.

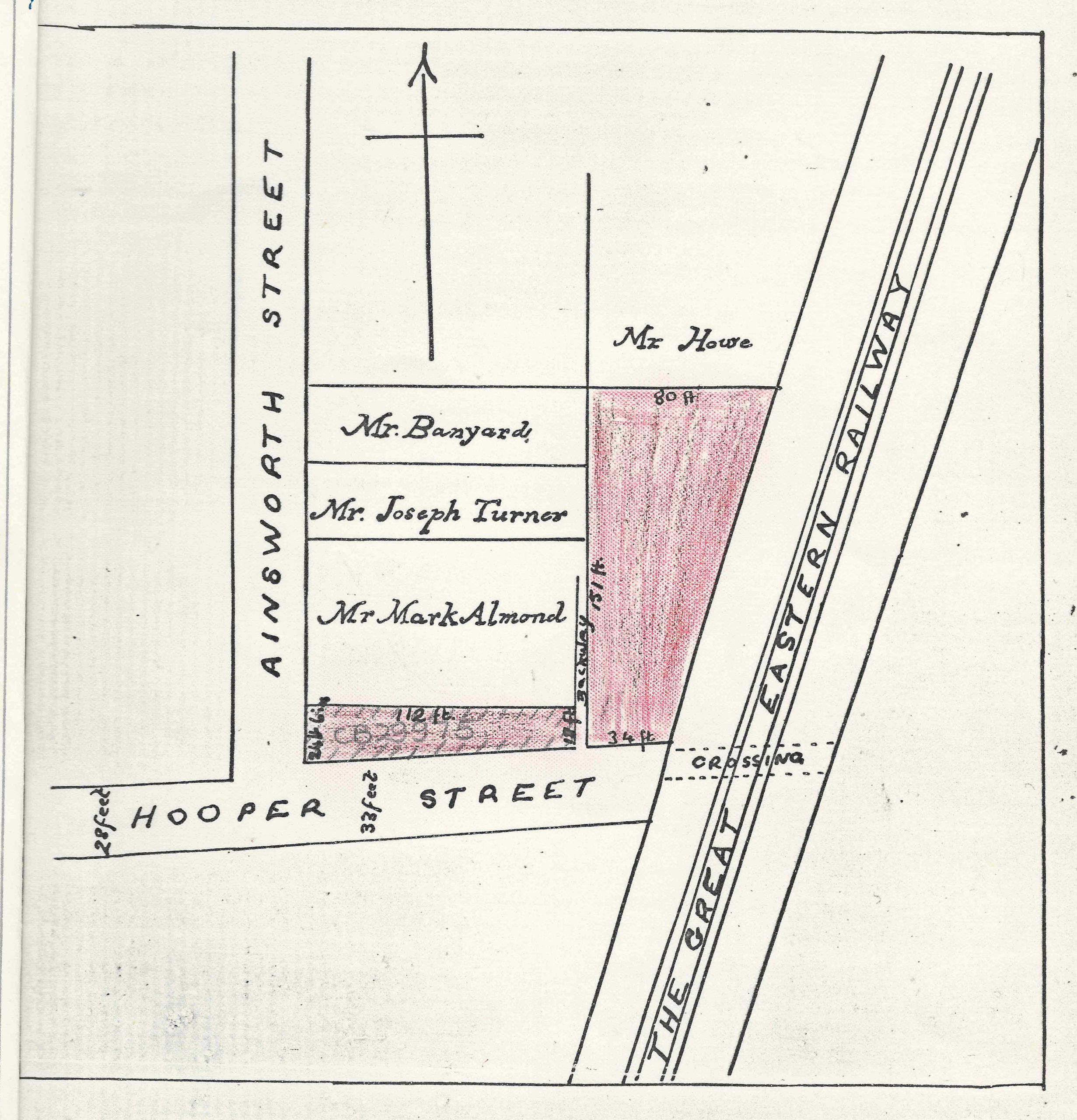

The shaded areas are the plots sold by Mark Almond in 1874, to Frederic Freeman. Source: deeds held by Calverley’s brewery.

In 1881, Mark Almond and his family were living at 106 Ainsworth Street, one of the houses he still owned. His occupation was now railway engine driver, a respected and well-paid job. Back in the 1861 census his occupation had been railway servant, an earlier stage in a career path that could lead to engine driving after years of hard work and study. It is possible that he had already qualified as an engine driver during the 1860s, and this is what enabled him to invest in property. Mark Almond died in 1888. By 1891 his widow Harriet had moved in with Florence and her husband William Allen in Beche Road.

1881 census for 23 Hooper Street

Charles Edwards, head, 23, gardener of publican ‘Eastern Tavern’, Coton, Cambridgeshire

Elizabeth Edwards, wife, 30, b. Ashby, Cambridgeshire

Frederic Ranson, wife’s son, 14, tailor’s apprentice, b. Cheveley, Cambridgeshire

In 1881 and 1891 the publican was not living on the premises. It is possible that the beerhouse occupied the ground floor only, and the upper floor, using the Hooper Street entrance, was treated as a private property.

The Ainsworth Street doorway, now disused. This would have provided entry to the downstairs when the upstairs was treated as a separate dwelling.

1891 census for 110 Ainsworth Street

William Dowsett, head, 65, gardener, b. South Church, Essex

Emma Dowsett, wife, 67, b. Haymarket, London,

Robt Hayhoe, boarder, 9, scholar, Warwickshire

Living with Emma and William was Robert Hayhoe, not described as a relation although he is only 9 years old. His motive for living with them may have been for his family to send him to school, looked after by an elder couple.

In 1886 one James Manning was tried for stealing three cabbages from the garden of William Dowsett of Hooper Street (Cambridge Independent Press, 18 September 1886). The defendant claimed he thought the garden was that of his friend Mr Wilderspin. It turned out that, ‘so ignorant was Mr Manning as to the boundaries of his friend’s garden, that he actually weeded the prosecutor’s turnips instead of Mr Wilderspin’s.’ The case was dismissed.

1901 census for 110 Ainsworth Street

Samuel Derby, head, 30, publican, own account, b. Cambridge

Emily Derby, wife, 29, b. Aldershot, Hampshire

Muriel V Derby, daughter, 6, b. London

Winifred M Derby, daughter, 5, b. London

Theresa Derby, daughter, 2, b. Cambridge

In 1891 Samuel Derby lived with his parents in Gold Street, the Kite, and his occupation was confectioner. His apprenticeship was not happy. Two years earlier he had narrowly escaped prosecution for absenting himself from work for two days (Cambridge Daily News, 12 March 1889). He claimed he had been unwell due to neuralgia, but his master had no sympathy. ‘He asked that his indentures might be cancelled as he was not happy. Everybody seemed to work against him.’ Fortunately a chemist testified that Samuel had bought medicine from him several times. Nonetheless, the magistrates ordered Samuel to perform the duties of his apprenticeship on pain of imprisonment.

Luckily he found his métier as a publican. In 1900 the newspapers carry reports of two pub skittle matches: Sam Derby’s Eastern Tavern Boys versus Con Griffiths’ team from the Waggon and Horses, Mill Lane (Cambridge Daily News, 12 and 29 January 1900). The Waggon and Horses team won the first match and the Tavern Boys won the second.

1911 census for 110 Ainsworth Street

John Clark, head, 43, builder’s joiner, b. Soham, Cambridgeshire

Jane Clark, wife, 42, b. Littleport, Cambridgeshire

Harold Clark, son, 18, bookseller and porter, b. Cambridge

Leonard Clark, son, 16, signal box hand, Great Eastern Railway, b. Cambridge

Ada Clark, daughter, 12, at school, b. Cambridge

Mildred Clark, daughter, 11, at school, b. Cambridge

Ernest Clark, son, 8, at school, b. Cambridge

Stanley Clark, son, 4, b. Cambridge

19 years married, 6 children

Carpenter and joiner John Clark, born in Soham, had come to Sturton Town by 1891 and never left. In 1891 he was lodging with retired leather worker Richard Farr and his wife Sarah at 19 Hooper Street. In 1892 he married Jane Crabb, and in 1901 they and their four children were living at 16 Hooper Street. By 1911, with two more children, they had moved along the street to 110 Ainsworth Street. In Kelly’s Directory of 1916, John Clark is described as a beer retailer.

The Clarks’ eldest son Harold died in 1917 in the First World War, and is buried in Belgium.

1921 census for 110 Ainsworth Street

John Clark, head, 53, joiner (carpenter), C Kerridge, Sturton St, b. Soham, Cambridgeshire

Jane Clark, wife, 52, home duties, b. Littleport, Cambridgeshire

Ada Maud Clark, daughter, 23, domestic work, college, Trinity St, b. Cambridge

M F Clark, daughter, 24, shop assistant (ironmongery), Eaden Lilley, Market St, b. Cambridge

Ernest E Clark, son, 19, warehouse porter (grocer’s), Hallack & Bond, Market Hill, b. Cambridge

Stanley C Clark, son, 14, warehouse porter (grocer’s), Hallack & Bond, Market Hill, b. Cambridge

Jane Clark died in 1925. According to the electoral registers, John continued living at 110 Ainsworth Street until 1929 with his children Mildred and Stanley. In 1930 two changes occurred: Mildred had married Charles Earl and the house had become 23 Hooper Street again. By 1931 we see another change: Mildred and Charles Earl had set up home next door at 108 Ainsworth Street, and John had moved in with them. He lived with Mildred and Charles and their children until his death in 1948, aged 80.

1939 Register for 23 Hooper Street

In 1939 the occupants were coal delivery driver James Brown, his wife Mary, her 23 year-old son Christopher Emery from her first marriage, and a ‘closed record’ – likely a child. In electoral register entries from 1934 and 1935 they were living with Mary’s daughters Mary and Edith Emery.

In 1970 the Star Brewery sold the house to Leszek Jakubowski, who used it as the registered office for a family firm. In 1978 it was sold to David Norman Sands.

Sources

UK census records (1841 to 1921), General Register Office birth, marriage and death indexes (1837 onwards), the 1939 England and Wales Register, and local newspapers available via www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk.

Thanks to the Calverley and Fordham families of 23a Hooper Street (in the same ownership until 1883) for providing deeds and other documents that enabled us to unravel the early history of the building.

Thanks to Friends of Mill Road Cemetery for further information on the Clarks.

Contribute

Do you have any information about the people or places in this article? If so, then please let us know using the Contact page or by emailing capturingcambridge@

License

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0